1824 ledger gives peek at city’s roots

By Irene Galea

After almost two centuries, an antique ledger book from Ottawa’s pre-Bytown days has made its way back home. The volume, dating to 1824, has been collecting dust in the storerooms of a small local history museum in Vermont for what might have been decades.

“They had no idea where it came from, who gave it to them or how long they’d had it,” said Carleton University professor Bruce Elliott, an expert in Upper Canada history who has analysed the newfound artifact in great depth and recently introduced it to the public.

Now, the text is shedding light on a previously undocumented community — a pioneer settlement in what today is Centretown.

The book belonged to George Lyman Bellows and Samuel Stacy, the owners of a general store that predates the construction of the Rideau Canal two years later, in 1826. The shop stood on a small peninsula — Richmond Landing — that projects into the Ottawa River about one kilometre west of Parliament Hill, currently the location of the Royal Canadian Navy monument, which was erected in 2012.

A book from this time period and location is exceedingly rare, according to historian Douglas McCalla, who specializes in the history of rural consumption in 19th-century Upper Canada. The ledger joins just two other known artifacts, a belt buckle and a family bible, as settler-era heirlooms from the pre-Bytown days, said Rachel Perkins, administrator of the Cumberland Heritage Village Museum.

Many Indigenous archaeological artifacts have been recovered and catalogued from the time before European settlement of future national capital.

The true value of the book, said Perkins, lies in what it can tell us about the people of early Bytown. “The ledger connects all these figures from the earliest days of Ottawa. It reveals where they lived, where they worked, and where they went to buy their groceries.”

Indeed, store patrons mention several well-known Bytown names, including Braddish Billings, for which the Billings Estate and Bank Street shopping centre are named.

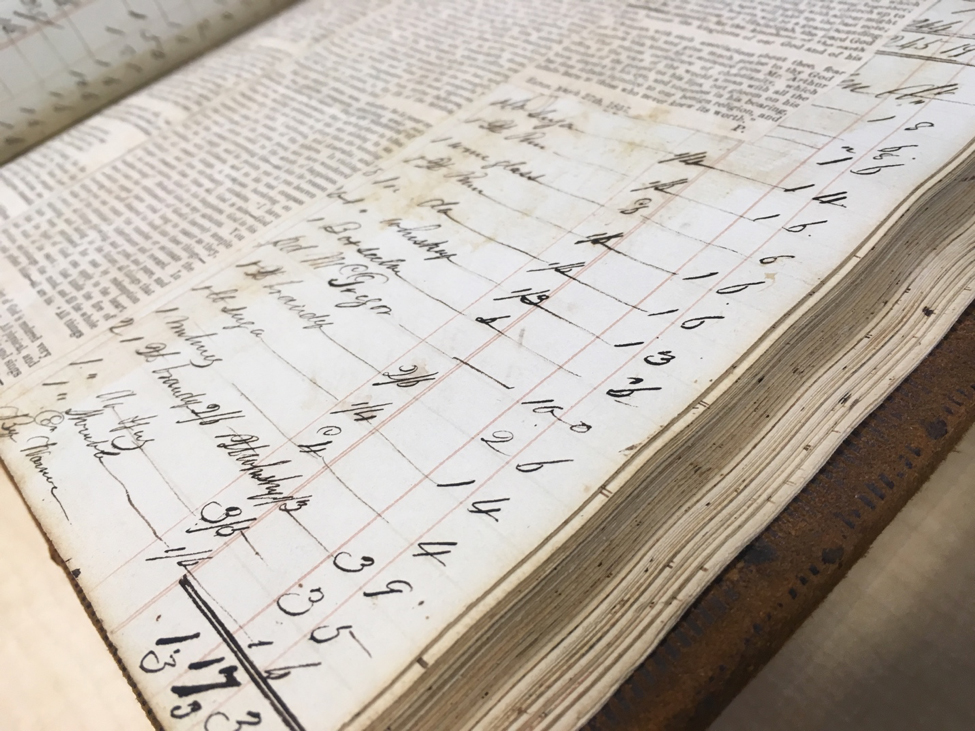

The four-inch-thick volume, which Elliott revealed to the public for the first time at Centrepointe Library in Nepean on Oct. 16, contains lists of purchases made by patrons. The range of goods stocked by Bellows and Stacy was exceedingly diverse; one particular patron, Rev. Amos Ansley, frequented the store for paint, pipes, linens and licorice. Others came in for turpentine or tobacco.

“Records like these are among the few places where historians can directly observe ordinary people going about their lives,” said McCalla. “Ledgers give us a richer view of economic life, and generally, a more complicated world.”

McCalla said that while the standard textbook suggests that pioneers in Upper Canada were self-sufficient, ledgers like this one prove that this narrative simply isn’t true. While businesses in early Bytown were in competition, they also had to work together.

Inscriptions in the Bellows and Stacy ledger tell us that they were, in fact, part of a co-dependent economic ecosystem. Raw goods such as wheat would be sold to neighbouring store owners, such as Philemon Wright, the area’s first white settler, who had set up shop on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River in what would become Hull.

Wright would mill down the wheat to flour, which, as the ledger shows, he would use as payment for other purchases. In turn, Bellows and Stacy would sell this flour to the cooks in the nearby lumber shanties, who would pay them off with wooden planks.

Perkins pointed out that the ledger reveals another connection between the early settlers: a strong link between Americans and Canadians over the border. “There seemed to be a lot of coming and going, back and forth. Nowadays, there’s Canada, and there’s America,” she says, motioning on either side of an imagined boundary. “So when does that boundary become firmly established? That just fascinates me.”

According to Elliott, this book is a rare find for another reason: it is a peculiar hybrid between the two standard record-keeping formats of the era: a day book, which included the transactions of the day, and an account book, which listed the month’s total earnings.

Instead, this seems to be an intermediate; the book lists all the transactions made by each patron over the course of a month. Elliott believes that the totals from each month would then be transferred to a separate account book, in order to record the totals without all the messy details of individual purchases.

Unfortunately, the ledger is not in perfect condition; during the 1860s, the nephew of George Bellows used the ledger as a scrapbook, pasting in newspaper clippings. Part of the conservation effort will involve carefully removing these articles and encapsulating them in acid-free mylar — essentially, laminating them — and then reinserting these sheets back into the book.

That way, readers will be able to see exactly where the articles were originally pasted in.

The book will then be digitized and uploaded into a special transcription software program, which will make it available to the public. Perkins said she expects that it will also be put on museum display at some time in the near future, with the exhibit to be announced post-conservation.