Carfentanil seized in Ottawa

By Michael Charlebois

The world’s most dangerous street drug, carfentanil, has made its way to Ottawa.

Police reported in early October that a Health Canada drug analysis of a heroin sample seized in Ottawa was actually a mixture of the opioids fentanyl and carfentanil.

Carfentanil is a chemical cousin of fentanyl but 100 times more potent; according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, it’s the most dangerous opioid known to science.

It’s used as an elephant tranquilizer. It’s been sold as a chemical weapon. Vancouver RCMP officers who seized a shipment in 2016 required hazmat suits to remove the substance.

Now it’s being cut into street drugs and sold on the illicit drug market as a cost-cutting method by dealers.

“There is no known application where carfentanil would be safe for human use,” a member of the Calgary RCMP said in a 2016 media release.

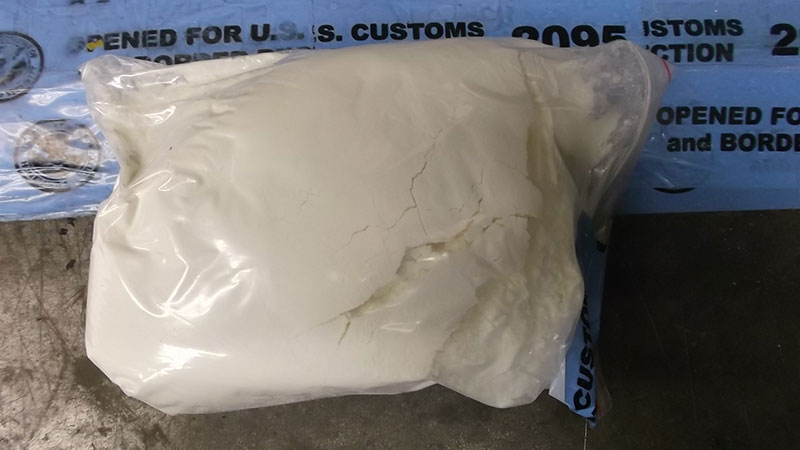

Carfentanil looks practically identical to table salt, and as little as 20 micrograms (less than one grain) could be fatal to humans. A photograph recently released by a P.E.I. police force showed dramatically how little carfentanil it takes to overdose compared with fentanyl or heroine.

“As far as investigating drug trafficking, it doesn’t change our mindset or priorities,” said Staff Sgt. Rick Carey of the Ottawa Police. “But we have to make the public more aware of the danger of it.”

Police first sounded the alarm earlier this year that carfentanil would likely show up in the capital. Ottawa, like much of the rest of Canada, is already grappling with an ongoing opioid crisis driven largely by supplies of fentanyl.

In April, Ottawa Public Health reported 15 opioid overdoses in a three-day period.

The latest provincial data revealed 1,898 emergency room visits in Ontario related to opioid overdoses from April to June. That’s a 76-per-cent increase from last year’s totals.

The provincial government recently committed to a three-year plan to help fight the crisis, setting aside $222 million in funds.

The money has already gone toward providing wider access to naloxone kits, as well as obtaining “fentanyl strips” that can detect the presence of the opioid.

The overdose antidote naloxone was recently issued to 600 Ottawa police officers — about half of the local force — in case they encounter overdose victims while performing their duties.

“It’s part of the public system with regards to our tiered response. It’s not just a police response. It’s paramedics, fire departments,” said Carey. “Hopefully the distribution (of naxolone) will help save more lives.”

Shannon Willmott of the Somerset West Community Health Centre said social changes are the first step in helping combat the crisis. In the midst of controversy in Ottawa over the a pop-up safe-injection site in Lowertown, the Chinatown-based health centre is awaiting word from Health Canada on its application to open an official supervised injection service in addition to one already granted to the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre.

“We need to see people who struggle with addiction as humans, and as people of our community,” she said.

Willmott believes supervised injection sites are a necessary step in fighting the opioid crisis.

The severity of the opioid crisis explains why the Ottawa Police has followed the Toronto force’s approach in not shutting down Lowertown’s illicit “pop-up” safe-injection site.

But are safe-injection sites prepared to deal with an opioid as strong as carfentanil?

Luc Cormier, nursing team leader for supervised injection services at the Sandy Hill centre, said the greatest challenge is keeping up with the change.

“We talk about it as a constantly changing environment for supervised injection services,” Cormier said. “It’s been five years since we began exploring this as a potential option. Things have changed drastically.”

Cormier said the government-supplied fentanyl strips — which have yet to arrive at local injection sites — can’t even detect the newfound carfentanil.

“Even with the strip testing… They don’t differentiate between fentanyl and carfentanil. So people are still not knowing what they’re using.”

One solution may lie in a research project being carried out at the University of Ottawa. Researchers there are developing a high-tech tool for “drug checking” that could provide an accurate and efficient way to differentiate between types of opioids, said Cormier.

“It’s a drug analysis… the gold standard in terms of checking for drugs. It looks at the weight of the different molecules,” he said.

“(The analysis) would occur before people use their drugs. And you use a very minute amount of the drugs, so it’s not like you have to give up half of your drugs. That way people could make an informed decision.”

Cormier said Sandy Hill is expecting to begin using the new test tool in December or January.