Echoes of Centretown spy affair in U.K. poisoning of former double-agent

By Meg Sutton

Hiding next door, Igor Gouzenko watched and waited while Soviet spies searched his Somerset Street apartment. They were looking for the 109 documents Gouzenko had stolen from the Russian embassy when he defected to Canada at the beginning of the Cold War.

Gouzenko arrived with his wife in Ottawa in 1943 to work with coded messages at his embassy; however, he quickly lost interest in helping the Soviets and chose to work as a double agent for Canada instead.

Passing the papers to expose an unknown spy ring that stretched across North America and the United Kingdom, his goal was to move his family “from Soviet slavery to democratic freedom,” he explained in his 1948 memoir, This Was My Choice. The Gouzenko documents are also credited with spurring Canada to build its own counter-espionage unit CSIS, and the papers demonstrated the infiltration of Britain by other Soviet spies during the war.

Now, history may be repeating itself. Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia are still clinging to life in Salisbury, in southern England, after allegedly being attacked by a Soviet-era nerve agent.

“In Canada today, the level of espionage is roughly the same as it was during the Cold War, and in a couple cases it’s worse than it was,” Robert Fadden, a former Canadian Security Intelligence Service director, said in a recent interview with the CBC. “I’ve talked to my colleagues in the U.K. and they’ve noticed the same thing. There was a real drop after the fall of the Soviet Union, but now we’re back to where we were again.”

If there is a modern day Gouzenko just around the corner, their identity cannot be revealed because “some of the work that we do is a bit dangerous,” Fadden said.

Double agents are only in danger if someone knows where their true loyalties lie.

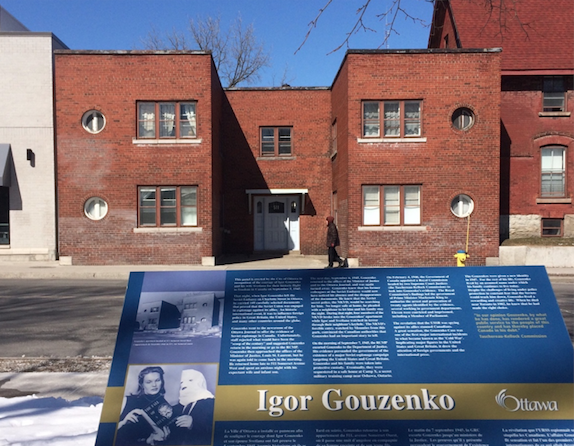

For that reason, after his defection, Gouzenko moved out of his apartment in Centretown. Nevertheless, it still stands today at 511 Somerset, across from Dundonald Park, and it played an essential role in hiding the newly Canadian spy the night he stole the documents.

Historian Jonathan Haslam thinks the reason Gouzenko was never caught was because the Somerset apartment building “had wafer-thin walls.”

In 1945, Gouzenko’s apartment was under surveillance by a Soviet military attaché who lived next door. However, the attaché’s wife did not like the sound of Gouzenko’s baby crying through the night, Haslam said, and as a result the couple moved out to escape the noise a few days before Gouzenko defected.

This left Gouzenko and his family alone, so “he could do as he pleased without prying Soviet eyes,” Haslam explained.

However, the building’s significance to Canada’s espionage history may be lost on other people living in the neighbourhood. Apart from a plaque in the park across the street, there is no recognition of Gouzenko.

“It’s pretty cool living so close to something I learned about in high school,” said Jason Bagnall, who lives directly behind the Somerset apartment.

He had not noticed the plaque across the street in Dundonald Park. “You expect there to be more recognition for something that important,” he said. “I would never had known because the building is so normal looking.”

So could there be another Gouzenko in our midst? Haslam argues in his book, Near and Distant Neighbours — A New History of Soviet Intelligence, that the “Gouzenko Affair” has significance in the modern day, for Russian intelligence methods and infiltrators still seem to be interested in Canada.

Other experts in Russian-Canada relations aren’t as convinced.

“It is hard to draw parallels to modern day spying since so much of it now is industrial (not military) espionage. And modern technology is so different, and satellite surveillance now does most of what earlier day spies tried to do,” said Larry Black, a professor at Carleton University who specializes in the study of Russia.

However, he does know of some suspicious activity. “Although it was not illegal, there was quiet observation of our professional hockey programs for years before they (Russia) challenged us, and almost won,” he said, laughing.

“We no longer have ‘defectors’, rather people who travel legally and sometimes try to sell often incorrect information,” he said.