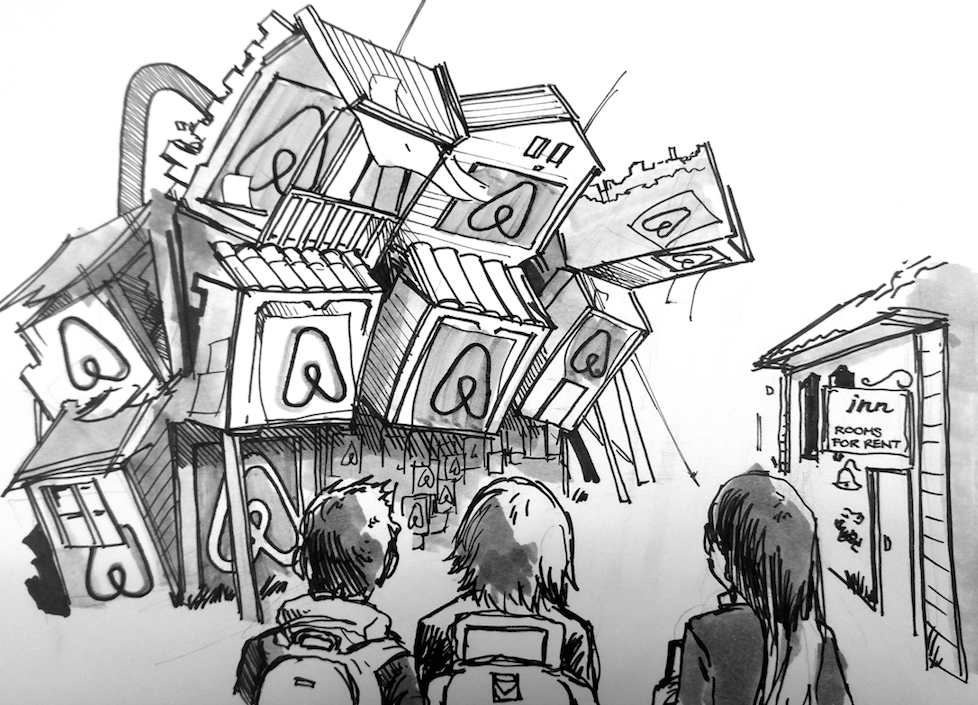

Editorial: Airbnb disrupting more than hotels

By Floriane Bonneville, Editor-in-Chief

The multinational lodgings company Airbnb finally struck a deal with the City of Ottawa last week, finalizing the details of a four-per-cent tourism tax that will apply to hotels, bed and breakfasts, and Airbnb units around the city.

The willingness of Airbnb to demonstrate that it is a good corporate citizen is laudable. So far, the company has struck similar arrangements with some 300 municipalities and other jurisdictions around the world.

However, there is a caveat to this collaborative gesture from Airbnb: it may charge its customers a tax to support local tourism marketing, but in the case of urban areas where rental housing can be scarce, Airbnb’s business model may be shrinking the supply and driving rents higher — creating a new form of gentrification, not from rich tenants, but from rich travellers.

The problem occurs when landlords realize that renting a room daily, or for a short-term accommodation to a visitor from out of town, is more lucrative than to rent monthly to tenants who will live in the community for the long term.

Those long-term tenants are part of the city and neighbourhood; they support local shops and businesses, build careers and families, contribute to the community in many ways.

Airbnb units devoted to serving the needs of tourists are, by definition, not available to local residents seeking rental housing.

In Montreal, the CBC recently reported on Andrew Chapman, a man who is the sole long-term tenant in a nine-unit condo building. The City of Montreal has more than 10,600 Airbnb listings overall, and they are extremely popular in Ottawa, too..

So that’s another thing that the City of Ottawa will need to look at in the future: how to protect tenants and neighbourhoods against too many landlords using too many spaces as daily rentals.

On the other hand, the premise of businesses like Uber and Airbnb is the democratization of urban transportation and tourism respectively; to make those services available to all and not subject to monopolistic providers. Now people don’t necessarily have to spend hundreds of dollars to stay in a downtown hotel room. Airbnbs are diversifying the kind of people who can afford to travel. That was Airbnb’s promise to the tourism industry from the beginning.

But like the taxi businesses that decried Uber as unfair competition, hotel operators have a credible case that Airbnb providers don’t face the same fees and regulations as traditional accommodation businesses. Municipal officials in many cities are rightly studying the overall impact of Airbnb in the marketplace to make sure the service it’s providing is safe for customers and not unduly harmful to other sectors of society, including people seeking rental housing. In Toronto, that issue is worrisome enough that city officials have proposed limits on landlords’ listing of units for Airbnb stays.

There is still a lot of work to do to make competition in the accommodation industry fair for everybody. Traditional hotels and bed and breakfasts are suffering because of Airbnb’s popularity. But there is no denying that the disruptive Airbnb has a rightful place in our modern, fast-paced society.

Municipal officials need to figure out the best way to create an even level-playing field for all who have a stake in the issue.