Editorial: City slow to respond to fentanyl crisis

By Nathan Caddell

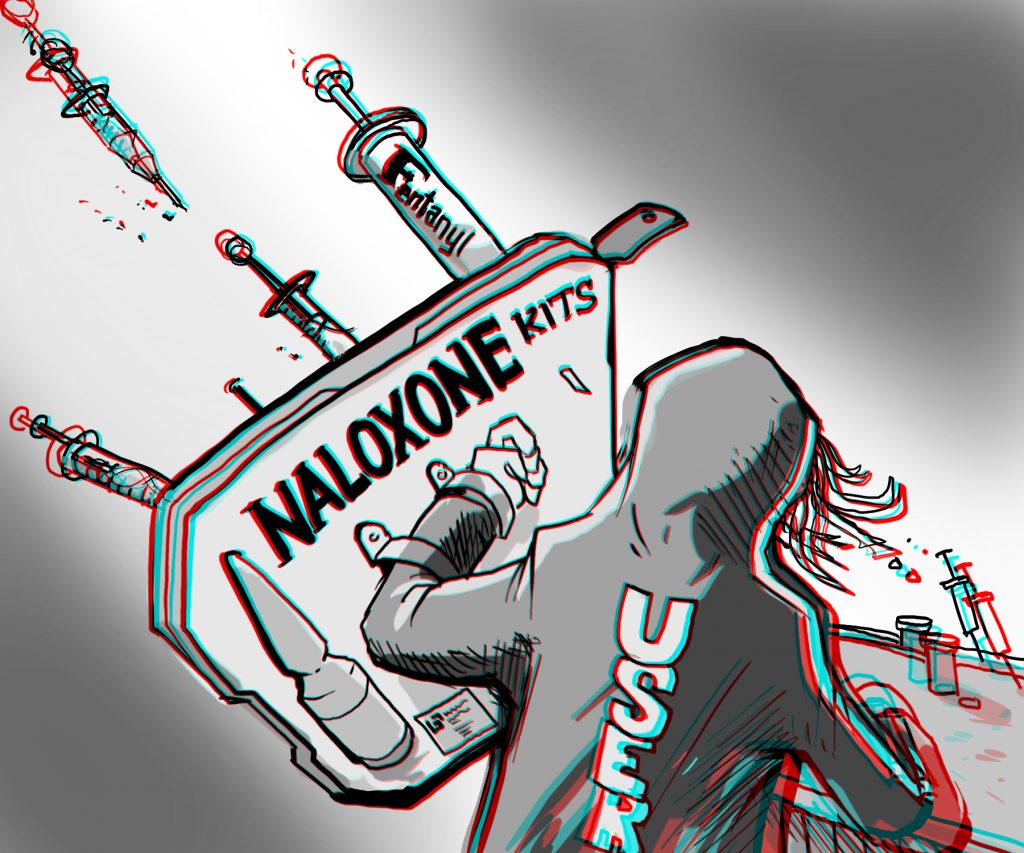

Earlier this month, it was announced that Ottawa firefighters would receive training with naloxone, the common antidote for fentanyl overdoses. This is unquestionably a good thing, as firefighters are often the first responders to arrive to a medical emergency.

Then, Mayor Jim Watson and Premier Kathleen Wynne agreed to a $2.5 million transfer to the City of Ottawa to help create more detox and treatment spaces, and provide police and firefighters with enough naloxone kits to do their jobs. This was another needed step.

Unfortunately, both of these measures came later than they should have. It wasn’t hard to look at the hundreds of lives lost to drug overdoses in B.C. in 2016 and to acknowledge that, inevitably, the epidemic would find its way to the nation’s capital. Even in Ontario, illicit drug overdoses increased 36 per cent from 2007 to 2014, the latest year for which province-wide data is available.

It took the Valentine’s Day death of 14-year-old Chloe Kotval, a Kanata high schooler, for Ottawa authorities to truly wake up and smell the poison.

The city’s inability to recognize that fentanyl was going to come to Ottawa points to a small town mindset that’s not acceptable for one of the biggest cities in Canada.

There is no easy solution for the fentanyl problem, but making sure Canadian cities are prepared for the drug is essential. Toronto Mayor John Tory seemed to understand this when he contacted Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson after the B.C. city experienced its worst-ever month for illicit drug overdoses in November, seeing an average of four deaths a day.

At the very least, November should have been when Ottawa officials started scrambling, having watched Vancouver’s situation escalate at a scary rate. Tory acted quickly, setting up a meeting with representatives of about 20 city organizations, including police, paramedics and hospital officials. He also immediately sought approval for three safe-injection sites in the city.

While Ottawa has recently moved to make Sandy Hill Community Health Centre a safe injection site, the $1.4 million allocated for the service, Rob Boyd, executive director of the Oasis Program at the centre, said is coming 10 years too late.

Watson has said he’d rather see public money spent on treatment programs than on safe-injection sites. It’s been proven, however, that services like Insite in Vancouver have tended to reduce local overdose deaths and increase the number of users going to treatment. In fact, evidence of that very nature stopped the once-skeptical Conservative federal government from closing the safe injection site back in 2011.

It’s not reassuring to have a “Big City Mayor” personally opposed to what many cities and health authorities have rightly seen as a solution to illicit drug overdoses, especially in the face of the fentanyl crisis.

Naloxone kits and safe injection sites are a start, but if the example across the country is any indication, fentanyl isn’t going away without a fight.

Hopefully, we are finally ready for it.