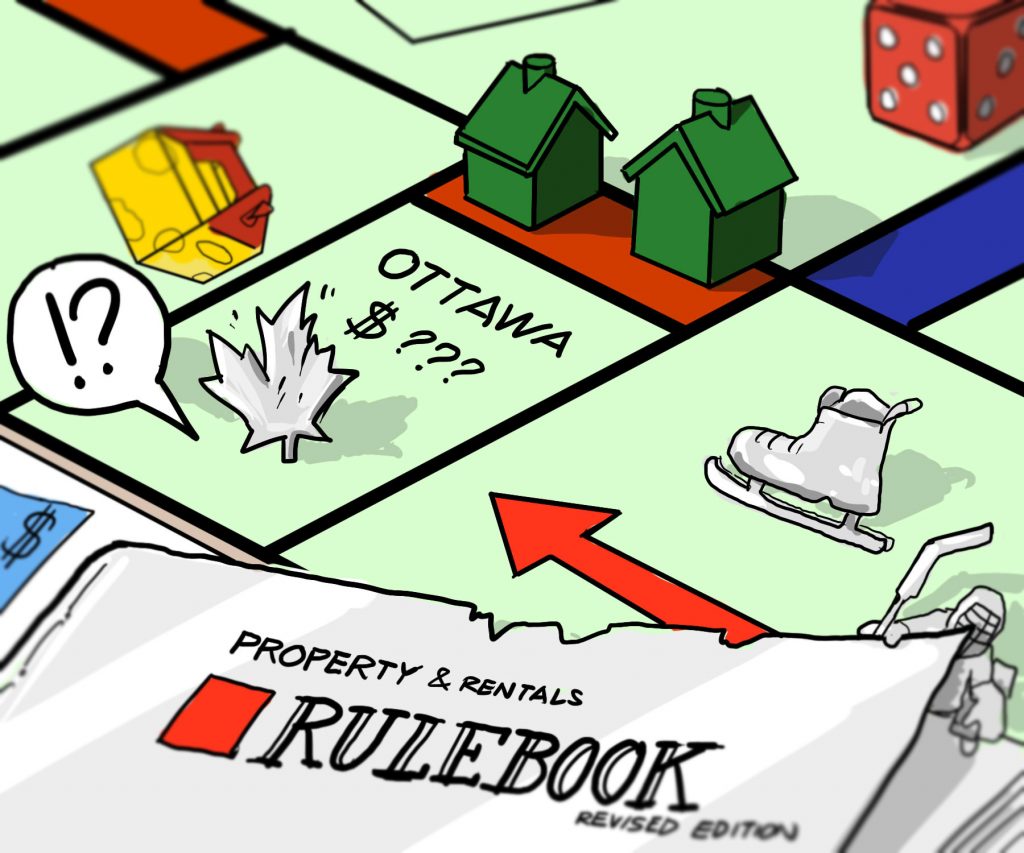

Editorial: Licensing landlords would benefit city

By Nathan Caddell

Rideau-Vanier Coun. Mathieu Fleury has joined the Ottawa branch of ACORN — an independent organization representing low- to moderate-income families — in pushing for landlord licences in the Ottawa area.

Last year, Toronto’s city council mulled the idea, eventually settling on tougher rules for landlords that required property owners to register with the city, have a pest management plan and use licensed contractors for all repairs.

Ottawa needs to follow Toronto’s lead and tighten this city’s rules, and Fleury is right in thinking that his ward is the place to start. Every university student has a landlord horror story, and, as many University of Ottawa and Carleton students call Sandy Hill and surrounding areas home, Rideau-Vanier would serve well for a pilot project.

And while landlord associations in Toronto — and, right on cue, in Ottawa — have spoken against landlord licences, ACORN and Fleury ought to take the initiative even further. The rise of Airbnb means that landlords, especially those in bigger cities, are able to charge irregular prices for days or weekends at a time.

While traditionally Airbnb deals are struck for brief periods while property owners are away, there have been documented cases in Toronto and Vancouver of residential units that are used strictly for Airbnb rentals at increased costs.

In fact, a MainStreet Research poll in Toronto found that 47 per cent of respondents believed that Airbnb should be regulated in some way. In Vancouver, the company itself recently removed more than 100 listings that it believed were posted by commercial operators. That, of course, begs the question as to whether other malpractice is teeming below the surface.

The proliferation of Airbnb means richer landlords and fewer spaces available for full-time residents of a community. If landlords were required to register with the city, it would not only help to hold them accountable for basement mould endured by regular tenants, but also to prevent quick evictions of residents or a general depletion of the city’s stock of rental units for increased profits from tourists.

For now, though, progress on the issue will have to be restricted to leaky taps and inadequate garbage bins and other routine landlord-tenant disputes.

Victor Menasce, president of the Ottawa Real Estate Investors Organization, which represents about 400 landlords in the city, tried to make the case that there is currently a system in place for tenants to make complaints.

He then seemed to admit that it wasn’t a very effective system. “We have laws on the books today. All it takes is a phone call. Dial 3-1-1 (the municipal hotline) and there is an enforcement mechanism,” Menasce told the CBC. “Layering another regime on top of an existing one because the first one isn’t working, how does that help?”

Ottawalandlords.ca, which bills itself as a “resource for Ottawa landlords,” gripes about how “residential landlords can only raise rent by 1.5 per cent,” and highlights “a regular stream of stories about ‘professional tenants’ abusing the system.”

That sounds a lot like shifting blame — and responsibility — in the wrong direction. Rethinking the rules in Sandy Hill makes sense to begin with, but as Ottawa continues to grow, all citizens would benefit from landlord licensing across the city.