Nation’s greatest movies grab Canada 150 spotlight

By Spencer Van Dyk

Fans of Canadian film are getting their fill this year thanks to an ambitious project showcasing 150 “essential moving-image works” to mark Canada’s 150th birthday.

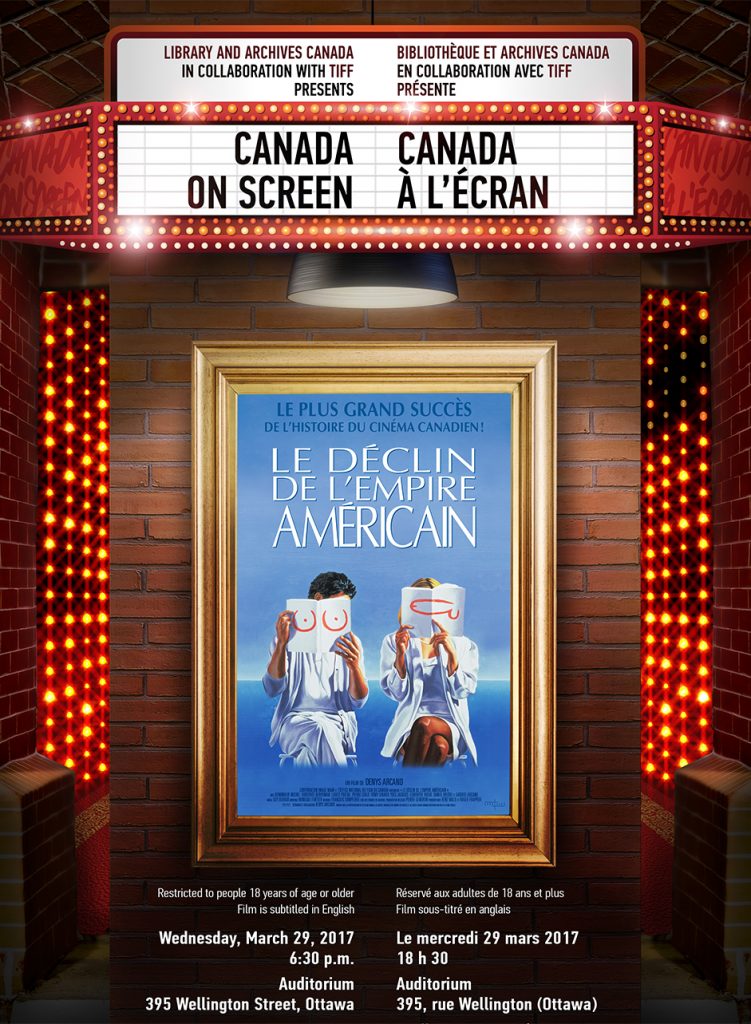

The Toronto International Film Festival has partnered with Library and Archives Canada, The Cinematheque and the Cinémathèque québécoise to present Canada on Screen, which TIFF director Piers Handling has called “the most ambitious retrospective of our country’s moving-image heritage ever attempted.”

The films included in Canada on Screen were chosen based on a poll of critics, scholars, and industry professionals. There are nine categories: feature films, documentaries, shorts, animation, experimental films and video, moving-image installations, music videos, commercials, and television shows. A list is available at tiff.net/canadaonscreen.

LAC’s Wellington Street headquarters is screening four of the films, which were selected by the agency’s archivists. The first was shown in February: Tit-Coq, a 1952 film based on a play by Quebec playwright and film pioneer Gratien Gélinas. It won numerous Canadian film awards, and was the first Canadian film to use rolling cameras and shoulder cameras.

The second Ottawa screening took place on March 29. It was Denys Arcand’s 1986 Oscar-nominated film Le Déclin de l’Empire Americain (The Decline of the American Empire), shown with English subtitles.

“It relates to a lot of what we’re living right now,” said Dino Roberge, the organizer and communications adviser for the screening. “The actors look 30 years younger and the costumes are a little different, but the text and the propos of the film is very similar to what we’re living right now in North America.”

Library and Archives is also lending the cinematic masterpieces to the Canada on Screen partners from the national collection.

“There are some movies that we have that nobody else has,” said Roberge.

He said there are 3,000 feature films in the national collection. The entire collection, which includes feature films, moving-picture film, public broadcast content, and government-produced audiovisual content, adds up to the equivalent of “hundreds of thousands of kilometres” of reeled film. To watch the entire collection would take more than 200 days.

The first Canadian feature film is believed to be the 1913 drama Evangeline, based on the Henry Longfellow poem, which is considered a “lost film,” meaning no copies are known to exist today, said Steve Moore, a senior audiovisual archivist at LAC.

“Preservation was not a concern back then,” Moore said.

Moore said the oldest surviving Canadian feature film is David Hartman’s 1919 silent classic Back to God’s Country, which starred pioneering Canadian actress Nell Shipman, but there are older and rarer materials in the archival collection.

Roberge said the next film to be screened in Ottawa will be Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, the 2001 film by Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk. It’s scheduled for a July showing.

The final film to be screened in Ottawa will be Back to God’s Country. A date for that screening hasn’t been set yet. Roberge said he’s looking to have a band or orchestra play during the original score of the film during the screening.

Produced in collaboration with artsfile.ca

The oldest moving-picture relic that LAC has is an 1894 Thomas Edison production called Annabelle Butterfly Dance, but it is not a Canadian production. It also has 1898 footage of what is believed to be the first hockey game on film.

Roberge said as soon as a Canadian filmmaker makes a movie, LAC typically gets a copy for archival purposes.

Moore said that much of the LAC collection is being digitized for easier public access, but whereas film can be preserved for around 150 years, digital content and players can be obsolete in about five years. Digitizing does not guarantee preservation, because technology is updated every few years, but digital copies online are easier for the public to search. Original film is preserved at a climate-controlled Gatineau facility with other LAC archival material.

Christa Nemnom, a third-year University of Ottawa student with a minor in cinema studies, said she heard about the screening of Decline of the American Empire from one of her professors.

“I wanted to see what it is, and why it’s so iconic in Canadian cinema,” she said.