Nightly projection honours soldiers killed during Great War

By Natalie Harmsen

As Remembrance Day approaches, the people behind a unique, international commemorative project are asking Canadians: How do we remember?

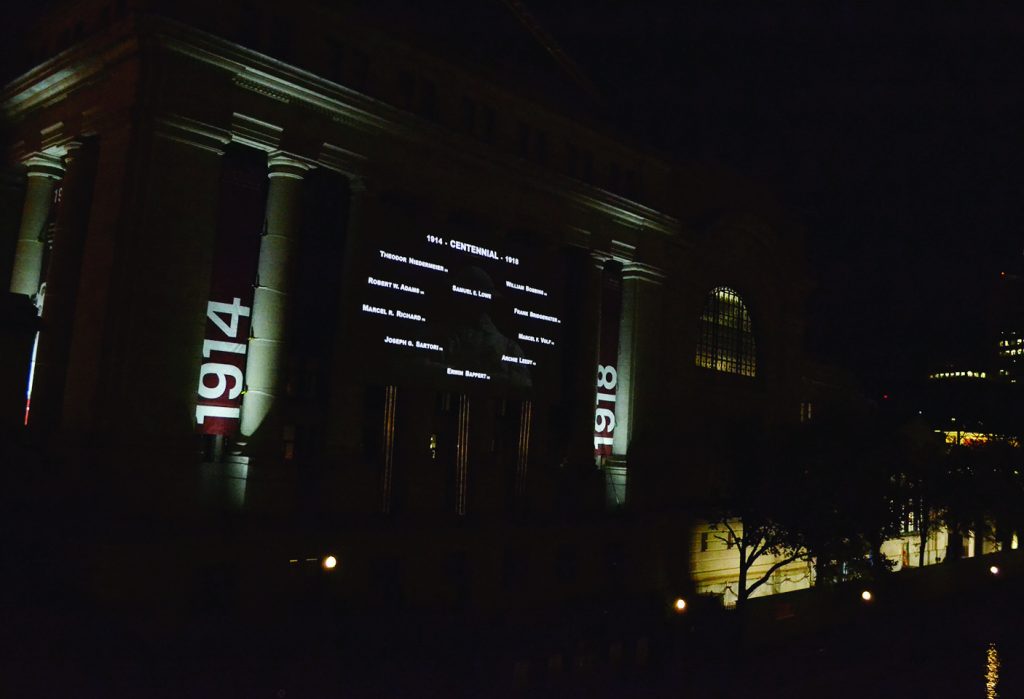

The Toronto-based non-profit organization The World Remembers is offering its own answer to the question by naming hundreds of thousands of those killed during the First World War in honourary displays across the globe — including a nightly projection of names on the side of the downtown Government Conference Centre leading up to Nov. 11.

This year, 661,837 names of soldiers killed in the 1914-18 war are being displayed around the world in libraries, museums, city halls and other locations as part of The World Remembers’ ongoing commemoration of the five centenary years of the conflict, originally known as the Great War.

In Ottawa, the names are being flashed on the side of the capital’s former central train station at 2 Rideau St. each night for 10 hours, a tribute that began at 8:30 p.m. on Sept. 24.

The projection slideshow begins with the statement: “The cost of war must not be forgotten.” The screen then fades to black, with the soldier’s names appearing in bright white letters. The Canadian names appear in the centre of the display, encircled by international names which are followed by their Internet country code. The international names dissolve, while the Canadian name remains alone in the centre for a longer duration before fading away.

Every 15 minutes, photos of the deceased soldiers appear.

The final name will appear at sunrise on Remembrance Day. The display is also running during the day at the Canadian War Museum.

“It’s impossible for us to show all the names in one year, so we show them 100 years afterwards. So the 2017 display is the names of those killed in 1917,” says the well-known Canadian actor R. H. Thomson, the producer of The World Remembers.

Thomson is working with Ottawa lighting designer Martin Conboy, whose other installations have included the National War Memorial and the Vimy Memorial in France.

“The project says that the most important thing, when you remember conflict, is to remember those who lost their lives. For 100 years, they’ve been referred to as ‘them.’ And in the 100th year after a war that was very questionable, and killed millions, we believe we should name them,” he said.

By including names from international armies, Thomson says, the project is a “large departure from the traditional way to commemorate.”

“Canada is all peoples now. Do you leave out the Italian Canadians? The Slovenian Canadians? The Vietnamese Canadians? The Sikh Canadians? Do you leave them out of commemoration? The World Remembers says no, because we are now everyone,” he said. “All those people should be included.”

Each name of those killed in 1917 is programmed to appear at an exact minute around the world through the participating nations: Britain, Canada, France, Germany, the U.S., Turkey, Belgium, Australia, the Czech Republic, Italy, New Zealand, Slovenia, and China. Names from the former British Indian Army are also included.

In Canada, 21,294 soldiers lost their lives in 1917, including those who died in the country’s most famous clash of the war, the April 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge. Every 90 seconds, on all the displays around the world, a Canadian name appears in the display, with 444 Canadian names appearing each day. The frequency of appearance of each name reflects the number of deaths from that country.

Thomson says seeing the names illuminated on the side of a landmark public building creates an emotional impact.

“We know if a name is scrolling, if you watch TV or a movie and the credits roll at the end it means nothing,” he said. “We know if a name stays still for at least 12 to 15 seconds, it stops being information and starts being a person. And at that moment, in reflecting on that person, that’s the point.”

Families can go to theworldremembers.org to search the names of their relatives lost in the First World War.

The Canadian War Museum was involved in the project last year and is “pleased to participate on such a big ambitious project” once again, said Caroline Dromaguet, the musuem’s manager of exhibitions and strategic initiatives.

Throughout the year, a film relating to the various exhibits is projected on the museum’s glass wall. Between the end of September and Nov. 11, regular programming is interrupted to participate in The World Remembers project.

“It makes a really good personal connection, seeing those names. I think it makes an impact on the visitor, and the person experiencing this will realize all the losses during the First World War,” she said.

“It’s all the soldiers combined, so it’s not just the Canadians, because we at the War Museum tend to speak more to the Canadian stories. But this is an occasion to speak more globally — it’s the war that affected everyone.”

Veterans Affairs Canada supplied the data for this country — the names of the dead — but the project was primarily financed by private donors. The Ottawa display was also supported by Commemorate Canada, the federal Canadian Heritage program that provides funding for remembrance initiatives across the country.

“Commemorating the service and sacrifices of Canada’s veterans and those who made the ultimate sacrifice is a key pillar of the Veterans Affairs Canada mandate,” said Marc Lescoutre, a departmental spokesperson.

Natalie Huneault, a spokesperson for the Department of Canadian Heritage, said the project “represents a meaningful way of honouring and understanding the First World War, which has ultimately shaped Canada, and Canadians, in profound ways.”

“(We are) proud to support The World Remembers project, which encourages Canadians throughout the country to remember the people of the First World War,” she said.

Thomson, 70, is best known for his Gemini award-winning roles in the films Glory Enough For All and Lotus Eaters. He was a recipient of the 2015 Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement, and was made a member of the Order of Canada in 2010.

For him, the most rewarding part of the commemoration is the reaction viewers have to the projected names.

“People understand that we are cutting through the habit of remembrance, and actually getting to the core of it, because I don’t think it’s about remembering a battle or a flag, or a war, or the fact that we won. I don’t believe that’s what remembrance is,” he said.

“I believe remembrance is remembering the individuals.”

This story was produced in collaboration with Artsfile.ca