OHIP+ helping youth with diabetes deal with financial burden of medication

By Madeline Lines

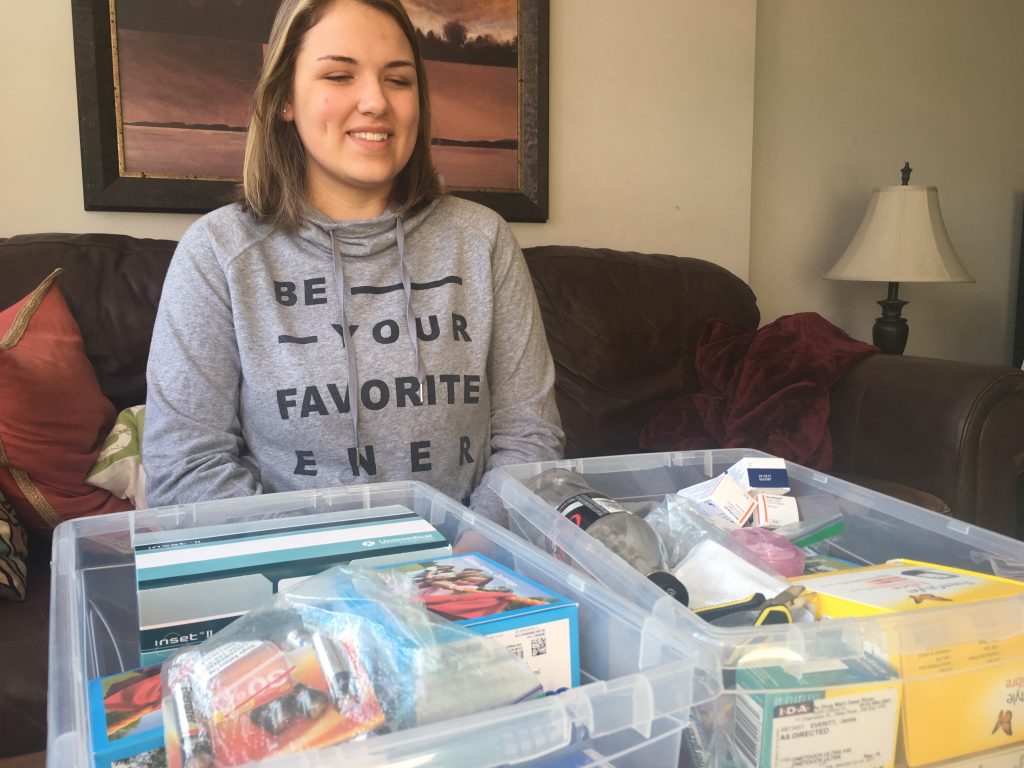

Jamie Everitt is a 21-year-old student with type one diabetes working in Centretown. Diagnosed at age seven, she got used to the painful prick of testing her blood sugar four to eight times a day, but the real shock was the price of the test strips — one dollar per strip.

Add that to going through a bottle of insulin every couple days, at about $20-30 a pop, and you have a financial burden that could appear unbearable.

Ontario’s new prescription drug plan, OHIP+, is covering costs like these for youth 24 and under. The program covers the entire cost of over 4,400 prescriptions — from cancer medications to contraceptives, and beyond. It is expected to cost $465 million per year in the province’s 2017 budget.

For many young people, this may be a welcome relief to already tight budgets. But for youth like Everitt, the financial impact of this program can be huge.

Luckily for Everitt, her parents’ insurance covers these costs while she is a student. She has been getting her medicine in bulk through her parents’ coverage when she visited home. But when she graduates next year and her parents’ insurance no longer covers her health costs, OHIP+ will spare her a massive financial burden.

“By the time I’m 25 —the hope is that I’ll have a job of my own by then, with benefits,” said Everitt. “Of course everyone wants that, but it’s especially important for someone like me that has a chronic disease.”

Nadia Boucher is a 22-year-old type one diabetic and Centretown resident who had been scraping by without any benefits. She said it was stressful trying to get the test strips she needed each month, and that she would often have to go to diabetic family members for emergency supplies.

She said the new program has affected her positively, lifting a stressful weight off her shoulders.

“Yesterday, I filled a prescription and saved $170 on four boxes of test strips,” she said.

Diabetes Canada has been advocating to the government for improved access to medications, devices, and supplies for a while, said Amanda Thambirajah, the organization’s director of government relations.

“Our recommendation doesn’t have an age cap on it, because diabetes doesn’t end at the age of 25,” said Thambirajah.

While Thambirajah acknowledges that the new program will be helpful for diabetic youth and children, she said the organization wants to improve access to anyone who may “fall between the cracks”.

Clients of Operation Come Home, a Gloucester Street support centre for homeless and at-risk youth, should be able to access OHIP+, said Lynda Franc, director of development. She said the centre needs to learn more about the program in order to assist OCH’s 600 youth clients in accessing it.

“The best thing that (the government) could do to help with the program rollout would be to increase awareness,” said Franc.

Many who will benefit, like Everitt, remain positive about the program’s impact.

“I think it’s going to be really great for all types of people — with epilepsy, with diabetes — just all types of people. 4,400 drugs covered is going to change a lot of people’s lives,” said Everitt.