While trees in downtown Ottawa have now donned their yellow, orange and red leaves, 25 lifeless trees were removed in late September and early October by the National Capital Commission.

Half had died because of Dutch elm disease, and others because of “urban and environmental stress,” according to the NCC. Among the removed trees were 14 elms, five lindens, four maples, one locust and one lilac.

“After lengthy treatment for Dutch elm disease in efforts to extend their lives, the 14 elms had to be removed as they posed safety concerns,” said Corey Larocque, a strategic communications advisor with the NCC.

Dead or weakened trees are more likely to lose limbs or topple over in wind storms, a potential danger to the public.

The NCC is responsible for many of Ottawa’s downtown trees, including those that inhabit some downtown parks.

The NCC intends to replace the removed trees at an “appropriate time,” and use knowledge of their decline to “mitigate the possible environmental stresses” involved, giving new trees a better chance at longer lives, according to Larocque.

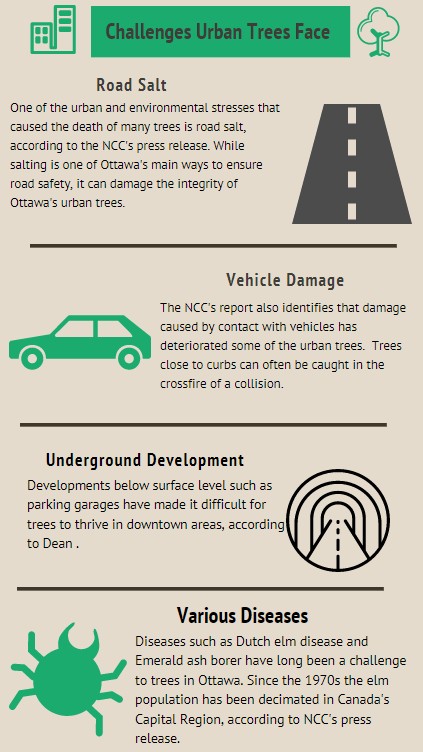

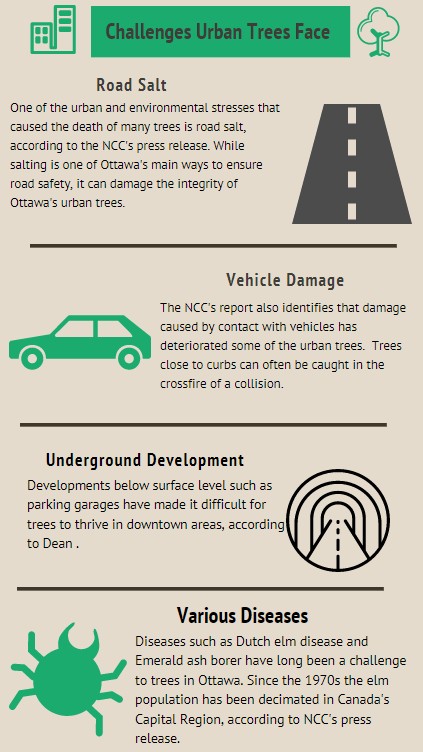

“Trees have always struggled to survive in the core of the city. Paving, then overhead wires, then salt and air pollution have made their survival increasingly difficult,” added Joanna Dean, professor of environmental history at Carleton University.

While maintaining Ottawa’s urban forest might be difficult, it plays a vital role and makes an “enormous difference to the mental as well as physical health of urban residents,” she said.

Treed areas improve mental health, promote physical activity and provide cooling in their immediate vicinity, according to the City of Ottawa’s website.

Problems with urban trees are not a recent development, according to Dean, who cited “asphalt roadways, concrete sidewalks, parking lots, and a labyrinthine infrastructure underground” as environmental stresses shortening their lives.

Diseases such as Dutch elm disease have also reshaped the cityscape, decimating Ottawa’s elm population since the 1970s, according to Larocque.

Similarly, many of Ottawa’s ash trees have also died and been removed because of the emerald ash borer infestation, which recently prompted an $8-million program to battle the effects of the invasive insect.

While removing lifeless trees from Ottawa’s downtown is part of the regular maintenance of the urban forest, trees in other urban areas face various threats, according to Paul Johanis, chair of the Greenspace Alliance of Canada’s Capital.

GACC works to protect green space across the region and has been consulted for the City of Ottawa’s Urban Forest Management Plan, according to Johanis.

On the left, a tree that has been removed since May 2019 on Wellington Street.

Johanis said the “big stress on urban trees comes from the way intensification and infill is planned by developers and approved by the city. There have been some improvements in relevant bylaws, but these are still ineffective and are not resulting in adequate tree preservation.”

The City of Ottawa cannot compel the NCC to adhere to certain bylaws. However, the work the commission does is expected to complement municipal tree-protection policies and projects, according to the City of Ottawa’s Urban Forest Management Plan.

Because of development, disease and urban stress, adequate “planting, maintenance and removal” must take place and are a normal part of managing the urban forest, according to Johanis. Adequate replacement of a diverse range of trees is pivotal to the health of Ottawa’s urban forest, he added.

With climate change as an issue at the forefront of the 2019 election, tree planting efforts were highlighted in campaign platforms. The Liberal party promised two billion trees over the next 10 years, while the Green party promised 10 billion trees over the next 30 years, according to their campaigns websites.