Little warrior

Randy Kakegamick's journey through the justice system

By Devon Litster and Ellen Spannagel

[Photo © Ellen Spannagel]

“I wanted my history to be told, I wanted the sense of being a person. That’s what it felt like, it felt like I’m not forgotten.”

– Randy Kakegamick

[Photo © Ellen Spannagel]

The way Randy Kakegamick sees it, his troubled journey through the justice system began long before he was born. His arrests, his charges, and his time in prison are all rooted from the experience of those who raised him. When he recounts his story, he reaches back to his parents’ childhood spent in residential schools.

“My parents, they were both taken from home when they were kids and sent to residential schools,” says Kakegamick, an Ojibway-Cree man from Ottawa. “That had a very big, very negative impact on the whole family, like the whole infrastructure of what people think is a family.”

Though Randy is a tall man, the stories he shares make him seem small. His voice is soft and yet the scars on his face speak volumes. He has seen a lifetime of challenges.

Left to right: Randy’s brother Eric, Randy, his mother Frances. The family spends time together in Waswanipi, with Randy swaddled in a copper Tikinagan. [Photo courtesy of Randy Kakegamick]

Randy starts his story with his parents’ history because he believes his experiences were shaped by something that was out of his parents’ control. In the residential schools they were forced to attend, their language was not to be spoken, their teachings were lost to them, and they were punished for their culture.

In Canada, around 150,000 Indigenous children were removed and separated from their families and communities and forced to attend residential schools across the country. It was a cultural genocide. The last Canadian residential school closed in 1996. In these institutions, hundreds of children experienced significant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. This trauma runs deep.

Randy’s parents never fully explained the hurt they experienced and it’s something he doesn’t ask about. He knows his mother, Frances, experienced trauma there because it is something she has had to deal with her whole life. Randy says his father, Abraham, became a withdrawn type of individual, someone who could be around people only with the support of substance abuse.

To cope with the trauma of their past experiences, both of Randy’s parents were led to addiction. Eventually the two were divorced, and their struggles influenced their ability to be parents to both Randy and his brother.

“They weren’t taught to nurture they weren’t taught to like hold us or, my mom would say she loves me and stuff like that yeah, but there was something lost, and I didn’t know what it was either,” Randy says. “I lost a parent who kind of wasn’t a parent in the first place.”

His experience as a self-described child-survivor of residential schools also denied him those relationships with his grandparents. His grandma, also battling with addiction and the pain of having her children taken away, couldn’t make it through one visit with her grandchildren without drinking. She eventually passed away as a result of her addiction.

“There was just this intergenerational stop of everything,” says Randy.

Due to these strained relationships, Randy spent most of his childhood alone. He learned to fend for himself and take responsibility into his own hands.

“I just felt really alone. I remember wandering the streets when I was a kid, like eight years old, seven years old and just cruising around downtown,” Randy says. “I’d pretend I was, you know, on an adventure, or just make up things to pass the time.”

He learned basic things such as cooking Kraft Dinner on his own and making sure his meals didn’t burn down the house. He spent time entertaining himself and becoming a ‘little warrior’ without any guidance.

At a certain point, he knew that things were different for his family; they didn’t have a lot of money. He knew his mom’s addiction could get them into trouble if more people found out about it, so he kept quiet about it.

“I had to keep it inside, you know. I had to not tell anybody that, oh yeah I was at home alone again, scared and crying.”

Later, he realized his family was different because of their suffering – the intergenerational stop they experienced. He’s known kids who grew up with parents that didn’t attend residential schools; he says he can see a difference in how they engage in life, with a connection to a culture he sometimes feels is foreign to him. A culture his parents themselves weren’t taught.

“Their leaning of their language was stunted, if anything. They do speak their language still but they forgot to carry on that with us, they weren’t really capable of teaching us how they were taught.

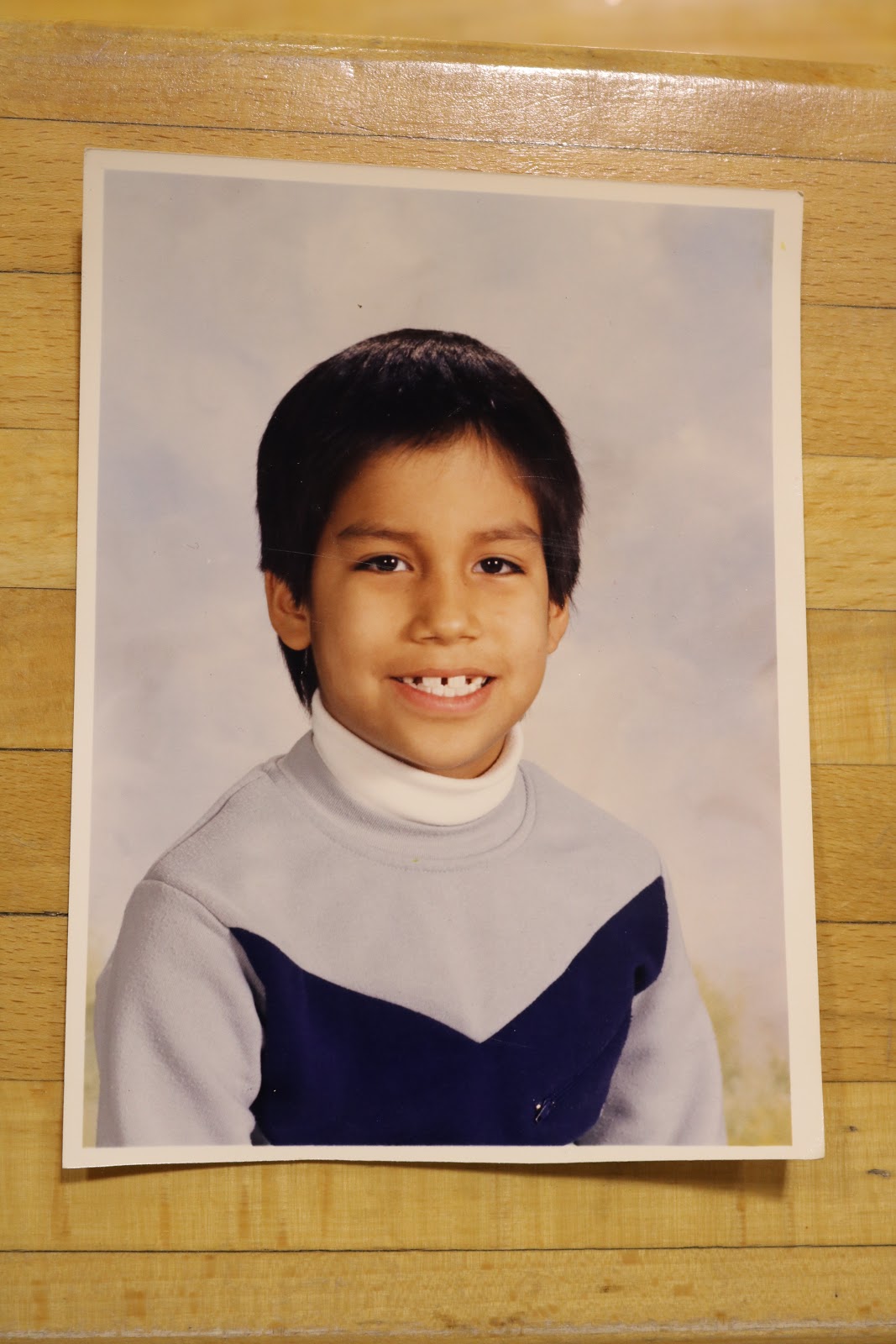

Randy between ages nine and ten. He happily remembers listening to Joan Jett in the Rainbow Diner. Other times, he remembers his loneliness at this age. [Photo courtesy of Randy Kakegamick.]

Randy himself can only speak a few words of his language Ojibway-Cree.

He did have one connection to their culture to hold on to, however. The music of his culture, the beating of his drum, is the only thing Randy remembers cherishing.

Randy says his drum was brought to him by a woman named Roberta, who wanted to bring the teachings of the drum to his community. She wanted to change their definition of what it meant to be men and show them how to connect to their community.

“Those parts of my life became a very special thing to me, those were the memories that I really had happy times in. Doing singing, just learning how to hit the drum together on beat and all these little things was making us stronger as little men, little warriors I like to say.”

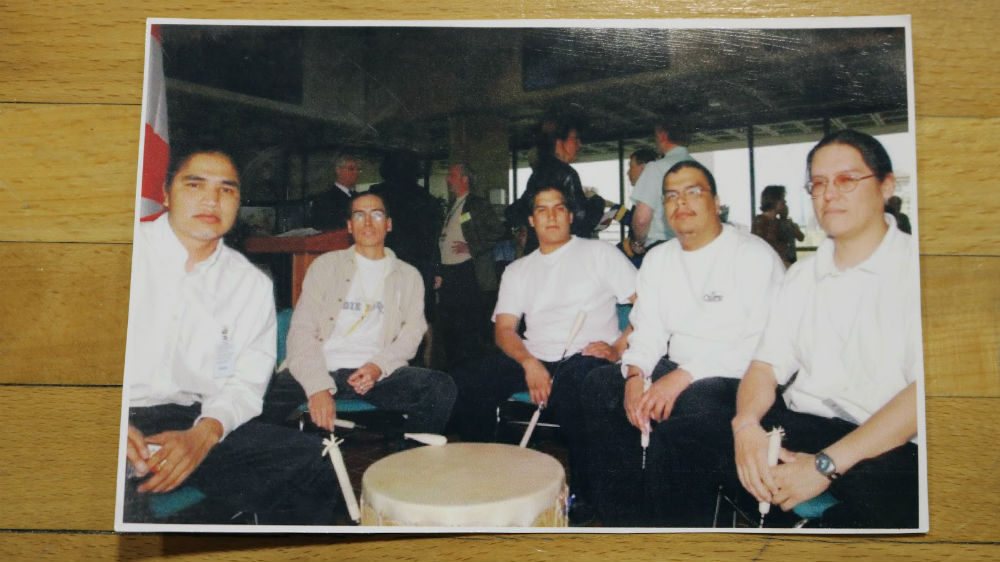

Left to right: Randy’s cousin Greg, friend Jeff, Randy, Erik, and Randy’s cousin Mark. As young men, they sang and played the drum together

and formed close bonds. These are some of Randy’s most cherished moments. [Photo courtesy of Randy Kakegamick]

The lack of structure in his upbringing led him to trouble. At age nine, Randy recalls feeling lost in school. At times he would ask other students for food when he didn’t have any. He had many long and hungry days.

Randy spent time causing problems and starting fights with other students without cause. He remembers picking fights with kids when he was having a bad day.

“I started really getting into trouble, doing all kinds of things that normal kids don’t really do because they have structure, they have small roles in their family to take care of things, and I didn’t have any of that.”

On top of fighting and schoolyard troublemaking, Randy began getting into more serious trouble with the law. He constantly pushed the boundaries set before him; he would steal and do other illegal things with friends. Including drinking and using drugs while underage.

Randy recalls joy-riding on a window cleaning scaffolding once; at the time he thought it was funny and harmless. He realizes now that his recklessness was dangerous.

At age 16, Randy knew he was an alcoholic after his first encounter. He battled with it up until a year ago, at age 40. He remembers his father dropping the role of an authority figure and becoming one of his “drinking buddies”. He thought it was cool at the time, but realized it wasn’t a healthy dynamic. By the time he was 20, his crimes turned more serious and he spent time behind bars for the first time.

Randy, age 12-13, after he and his mother moved to this new house, he felt a shift in their relationship and part of him began to resent her. [Photo courtesy of Randy Kakegamick]

Randy says he was charged with domestic violence a few times with a few different women. Some of his charges were also a result of public intoxication.The first time he served jail time was a result of an incident with his daughter’s mother. He spent eight months in a medium security facility in Merrickville.

Randy also found himself in fights that severely scarred him. At one time, he was slashed so brutally that he believed he had lost his nose.

He describes all these stories calmly. This was his normal.

He ended up with longer sentences each time he was arrested, going from 20 or 30 days to 90 days. Eventually, the time in jail snowballed and he spent a total of almost five years behind bars. Randy found himself in a “pleading guilty cycle”. His lawyer would tell him that the small offences were nothing and not worth fighting. So he didn’t.

When he was released, the cycle would continue. He would relapse, find his way to the bottle, and end up back inside over and over. The lack of resources and treatment provided for his addiction made it difficult for him to avoid encounters with the law.

Because of the intoxication, Randy had trouble remembering most of his offences. His history led him to believe the worst in himself.

“I told my lawyer, if they’re saying this is what happened, I guarantee it’s probably true. You know, I have this sense of guilt right now that they can’t not be true,” Randy said after one offence he was too intoxicated to remember.

Randy felt like he was forgotten by the system. He felt regret, shame, and anger with himself. An experience, he says, that is echoed by other Indigenous inmates just like him.

For Randy, breaking his cycle began with telling his own story. He did this through a Gladue report, which offers a comprehensive history of an Indigenous individual to give context to their upbringing for judges to consider when sentencing.

At first, Randy was daunted at the idea of telling stories too painful to put into words.

“I was ignoring it. Because I was so deep in addiction that I didn’t want to face it. Who wants to tell those kind of stories?”

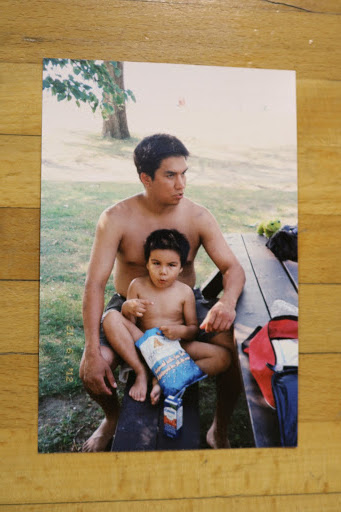

Randy and his son, Isaiah, at the beach. At this point, Randy was still battling alcoholism while trying to be there for his son. [Photo courtesy of Randy Kakegamick]

Randy first began his Gladue report with the intention of having Mark Marsolais, someone he knew through from the Odawa Native Friendship Centre, write his story. Due to the time constraints placed on them by the court, he was forced to use a court-appointed writer.

In the spring of 2017, Randy’s story found itself in the hands of Kara Loutit, one of the only official Gladue report writers in Ottawa. When Randy met with her, he sat down and immediately told her how he wanted their meeting to operate. He wanted to say his piece, fully, and just have her listen.

“The only way we’re going to get this done as if you let me share everything that I feel like sharing and I get to oversee everything that you’ve written. I don’t want anything to be put in there that’s a little too far.”

Gladue writers have to be responsible, because including certain information can lead to families getting into even more trouble with the law.

Randy and Loutit met several times, taking nature breaks, and getting to know each other on a personal level. “It was really emotional,” Randy says. “Going through all this stuff with a person I didn’t know. I had to build a sense of not pride, but strength.”

When he finally had a finished copy of it in his hands, Randy felt like his story was finally being heard. After all the years of cycling in and out of prison and addiction, he finally felt like this time could be different.

“I felt like this was my chance to say hey, I have history that is distinct to anybody in this country, along with numerous other First Nations people who are locked up. And nobody gets a chance to voice it like I did.”

After his judge read his report for the first time in court, she apologized for all that he had experienced, on behalf of Canada and all that it put him through. However, not all judges take the same approach. Randy describes having had several Judges who simply said they “considered the Gladue principle” before moving on, brushing it aside.

For Randy, if there is going to be justice for Indigenous peoples in Canada, then considering the grim history is necessary. “That’s the kind of people we need. Those are the kinds of writers that guys like me who were inside need,” he says.

He hopes this can lead to more methods of restorative justice- community programs and treatment built on Indigenous culture, as well as more lenient sentences, rather than lifetimes behind bars.

Getting the Gladue report was a chance to reshape his path in life on his own terms.

“It’s like taking a big breath. It’s like definitely getting my head above water,” he says.

Working through his past is an ongoing and trying process, but one he’s willing to fight for.

There are times the immense burden of the past still weighs him down.

He has been denied the opportunity to visit his grandson Eli Jeffrey, due to the broken relationship with the grandmother.

There are moments where he is too tired and too overwhelmed to give his son Isaiah, age 10, the time he knows he deserves.

But Randy fights on.

“I push through because I remember what it was like to be ignored too as a kid, and I want him to feel the love that I lost.”

Randy and Isaiah like to go on little adventures together; they spend their time hanging out and talking, and Randy always ensures his son feels heard. Sometimes they talk about superheros, other times Randy is checking in to see how Isaiah feels at school with his friends.

Getting the Gladue report done was a huge stride in Randy’s attempt to seize control over his own life, and end the intergenerational cycle that brought him to the mercy of the law in the first place.

“I started out on the route, on the same path as my father with my son. But I put an end to it. Two years almost five months now. I had to,” Randy says.

Randy performs with his fellow singers and drummers, bringing the beat and rhythm to the sacred circle. [Photo © Ellen Spannagel.]

Part of Randy’s path to being the person he wants to be is putting music at the forefront. He is a student at Algonquin College for Digital Music Production, where he wants to become a music producer and promote local artists.

Singing, dancing, and beating the drum at Powwows across Ottawa gives Randy a way to give back to his community while engaging in the music that he loves. More than that, it has given Randy a haven where he can heal and grow.

When he dances, Randy fills every inch of the sacred circle. His eyes are filled with light and excitement, and he no longer carries the weight of his past. He is a vibrant force of energy.

Randy also was asked to teach the younger generation, ‘little warriors’ as he would say, the art of dance and ritual. This is a huge honour for him.

Randy danced tirelessly throughout the day. His outfit, which is the product of several hours of work, is a huge source

of pride and honour to him. [Photo © Ellen Spannagel]

“I can’t believe I’m being asked this. From sitting in a cell or sitting in solitary confinement to now being somebody a kid can look up to, it’s really inspiring for myself,” Randy says.

Even after the moments of pain and doubt that his journey brought to him, Randy sees his life now with a sense of satisfaction. “I do have those moments now where I can say I’m proud finally. I really did not feel that sense of pride for a long time,” Randy says.

Randy Kakegamick is one of the lucky ones. Gladue reports are hard to come by for Indigenous inmates. Many of them are left without options.

Between 2016 and 2017, Indigenous adults accounted for 27 per cent of the federal correctional population, while only representing 4.1 per cent of the overall Canadian adult population, according to Statistics Canada.

“There’s the inmate that sits in his cell that’s so full of loneliness and so full of hurt and so full of pain that he doesn’t want to go see a social worker, he just wants to do his time,” Randy says. “There has to be better way to reach him.”

Randy never knew he could love someone in his life as much as he loves his son, Isaiah. [Photo © Ellen Spannagel]

[Photos © Ellen Spannagel]

To write this story, we sat down with Randy Kakegamick and listened. It was a process of several hours of openness and trust. We are honoured to have written this story: Randy, Meegwetch.