Jason Michelin has worked over 30 jobs in his life, but out of them all he likes the title entreprenuer best. [Photo © Boshko Maric]

“I’m anti-capitalist”: how one Inuk entrepreneur is including cultural values in his work

Self-proclaimed “Inuk-preneur” Jason Michelin says he’s on his own due to lack of funding.

By Angel Xing, Boshko Maric, Sember Wood, Ashley Keller

Typing sounds fill Jason Michelin’s home office. His profile is backlit by his two computer screens as he works on the numerous projects he has on the go.

An Inuk from Goose Bay, Labrador, Michelin calls himself an entrepreneur, but has redefined the word’s meaning as it pertains to him and his work.

“As much as I’m an entrepreneur, I’m anti-capitalist,” Michelin said.

While capitalism prioritizes profit, Michelin envisions a different kind of economy.

He references the word’s Greek origins, where ‘economy’ translates to ‘household management.’ It’s about building wealth to care for the community and environment, which Michelin says aligns with Inuit values.

“Every human being on earth has an inherent responsibility to take care of nature and Mother Earth for themselves and future generations.”

The Inuit value of community wellbeing

Community wellbeing is fundamental to Inuit economies, says Emilie Fortin-Lefebvre, a professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal. She leads a research centre studying Inuit economic autonomy.

“Very rarely an Indigenous entrepreneur … will do something only for themselves,” Fortin-Lefebvre said. “They always want to give back to the community, create more jobs or give services to … people that don’t have services.”

Fortin-Lefebvre describes Inuit entrepreneurship as a path toward economic autonomy. “It’s a way to protect traditional culture, a way to enter the economy while doing it on their own terms.”

Karen Orser agrees. She’s the employment manager at Tungasuvvingat Inuit (TI), a non-profit supporting Inuit across Ontario.

“People are preferring to be in the entrepreneurial system because they understand what they need to do in their own way,” Orser said. “They don’t want to be part of the colonial system.”

Orser sits across the meeting table at TI wearing a shirt with a design of Inuk artist Kenojuak Ashevak’s Enchanted Owl (1960). She says she’s hopeful for change and is doing what she can to support entrepreneurs. [Photo © Boshko Maric]

“I know it is a non-profit, and even I may come and go,” Orser says. “But that doesn’t stop me from planting those seeds because I have seen that they do start to take. They do start to grow.” [Photo © Boshko Maric]

Michelin has created multiple projects in the spirit of venturing beyond the colonial system. His first project was a game app called Tulip Crush.

Now, he’s working on bringing “Inuitsy” to fruition. The project is a play on Etsy, a digital sales platform for self-employed artists.

Besides taking a sizeable cut from vendor sales, Etsy has been under scrutiny for ethical concerns like removing Inuit artists’ sealskin items from the site.

Michelin’s “Inuitsy” is made by and for Inuit artists, but he wasn’t able to find enough funding to get it started, leading him to take on the initial cost of the business.

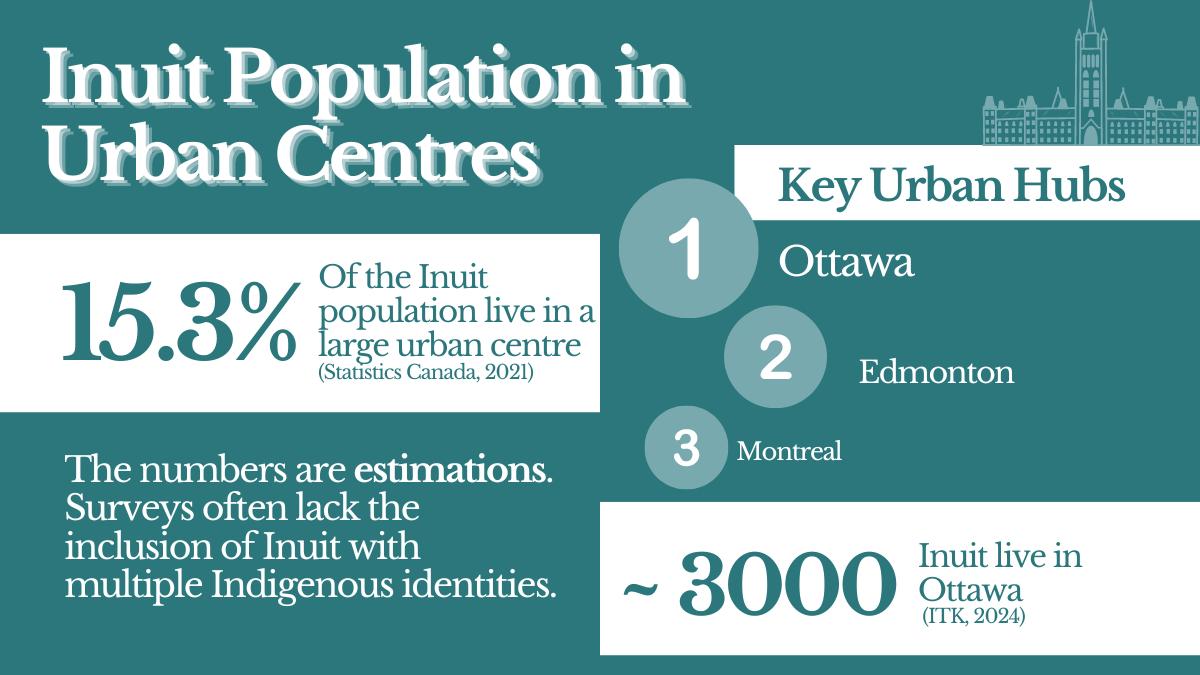

He says he’s not alone. Ottawa is the biggest urban hub for Inuit outside Inuit Nunangat, their homeland up North, but Michelin says there aren’t many accessible resources for budding Inuit entrepreneurs.

[Graphic © Angel Xing]

Finding funding for Inuit entrepreneurship

TI is one of the only Inuit-specific urban service providers in Ottawa and the first stop for hopeful entrepreneurs. It receives employment funding from the federal program, “Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program” (ISET).

According to Orser, Northern communities get most of the funding, forcing her to make some difficult calls for applicants in Ottawa.

“We have to go with where the bigger need is,” Orser said. “What [entrepreneurs] really need in terms of money for that year could potentially send other Inuit through post-secondary certificate training.”

The other two main options for federal funding include the Community Opportunity Readiness Program (CORP) and the Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program (AEP).

CORP isn’t for independent entrepreneurs, and AEP is only available after they’ve been denied business loans.

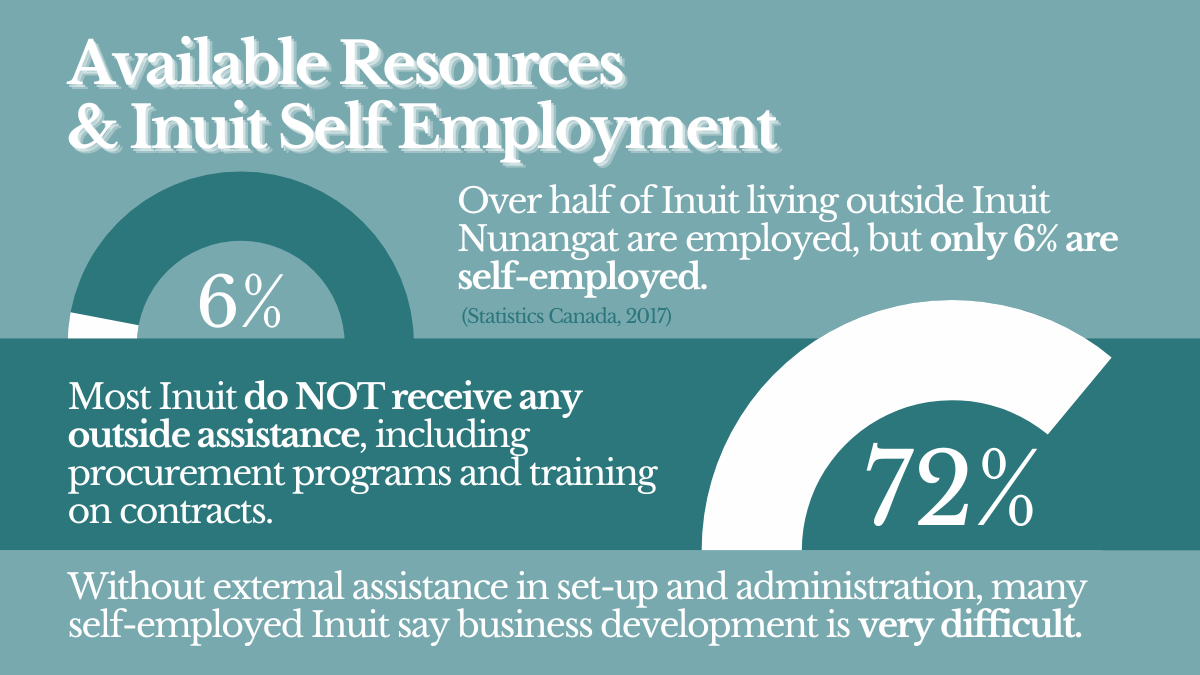

[Graphic © Ashley Keller, Angel Xing]

Grants for Indigenous entrepreneurs are also often First Nations-centred, and don’t cater to the different cultural needs of Inuit entrepreneurs.

Michelin remembers an instance where grants for Indigenous entrepreneurs given out by Service Canada were offloaded to regional First Nations representatives. Michelin couldn’t apply because he had to state his Band membership, and unlike First Nations, Inuit don’t have Band membership.

Rejecting corporate sponsors

In his 12 years as a solo entrepreneur, Michelin has faced challenges for refusing to compromise his anti-capitalist values while working within a capitalist system.

Michelin says he first pitched Inuitsy to Shopify since the company claims it wants to help Indigenous entrepreneurs. Shopify expressed interest, so he sent them a business plan.

“I really solidified what I thought was a serious effort to bring everyone together to show that their words could be put into action to actually create fundamental change,” Michelin says. “The CFO at the time ghosted me.”

“If they really meant what they meant, in good faith with integrity, they would have replied—any one of them.”

He also passed on Pow Wow Pitch, an annual competition funding Indigenous entrepreneurs in Canada, when he learned RBC sponsors it.

RBC has contributed funding to the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline running through Wet’suwet’en homelands in British Columbia, despite opposition from hereditary chiefs.

Without grants, Michelin pays the bills and funds his business endeavours through contract work in IT and side hustles like flipping software.

Dreaming big for the future

Despite setbacks, Michelin doesn’t plan on giving up. Part of his anti-capitalist mentality means he, like many Inuit, wants to share information freely to empower his people.

The first collection that will be sold on the site is Michelin’s “Ancestors Anew” series shown here. He used AI to upscale public-domain colonial paintings of Inuit from as far back as the 1570s. Inuitsy is part of this plan, and Michelin hopes Inuitsy will be ready to go live in the coming weeks. [Photo © Boshko Maric]

Michelin’s ultimate dream is bringing his knowledge back to Goose Bay.

“I do have some ambitions to do what I can to better my community, better my life, my family’s life, and everyone around me,” Michelin said. “Hopefully get my spot out in the middle of nowhere, which I’m gonna call Shangri-Labrador.”

“That’ll be my little utopia.”