John Paul Kohoko sets up trail cameras in Algonquin Park as part of the Anishinaabe Moose Committee’s initiative to monitor moose populations on the Ontario side. [Photo provided by the Anishinaabe Moose Committee]

How the Pikwàkanàgan First Nation is combating moose population decline in Algonquin park amid climate change

Hunters from Pikwàkanagàn are working with the Anishinaabe Moose Committee to document and understand why moose populations are dropping while incorporating Indigenous knowledge into prevention strategies.

By: Natasha Baldin, Madison Flaro, Robyn Best, Camille Green

Several years ago, when John Paul Kohoko found himself face-to-face with the biggest moose herd he had ever seen, all he could do was lean against a tree and stare.

“No thought of mine ever wanted to harm any one of them. Even though I had a gun, I just put it there and said, ‘This is amazing.’”

“There were small ones, big ones, mothers, cows, calves, small bulls — there were 15 to 20 moose. I wish I had a camera, but all I could do was sit there in awe,” he said.

Kohoko, a member of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, has been hunting moose in Algonquin Park since he was young, learning how to feed his family and sustain his Anishinaabeg culture.

But, amidst widespread declines in moose populations across Canada, Kohoko knows he can’t take these moose sightings for granted. In Ontario, moose populations declined by 20 per cent between the early 2000s and 2017, according to the Government of Ontario.

“We see the change first-hand when we go to Algonquin Park — it’s totally changed compared to what it was and it’s very hard to watch,” Kohoko said. “We used to go for a drive in the park and see 25 moose, but now you’re lucky to even see one.”

Kohoko is the first Ontario member of the Anishinaabe Moose Committee, a grassroots project informed by Indigenous teachings which aims to document and protect moose on Algonquin lands. As moose experience warmer winters and shifting ecosystems caused by climate change, hunters in Pikwàkanagàn say it’s important to do everything they can to maintain the Anishinaabe tradition of moose hunting.

The Anishinaabe Moose Committee monitors moose populations in Algonquin Park using trail cameras installed onto trees. [Photo provided by the Anishinaabe Moose Committee]

Factors driving moose decline

Algonquin Park is home to approximately 2,650 moose, according to the most recent data collected by the park.

While moose populations are faring better in Algonquin Park than they are in many Quebec provincial parks, the committee decided to shift research to the Ontario side due to observed effects of moose decline by Pikwàkanagàn hunters.

“We wanted to go see for ourselves, looking into why [Algonquin Park] would still have a good number of moose in the area,” said Shannon Chief, the Anishinaabe Moose Committee project co-ordinator and member of the wolf clan.

The committee was formed in 2021, composed of members from several Algonquin nations in Quebec. Now, they’re expanding their work to conduct moose surveys, mapping and install trail cameras in Algonquin Park.

Provincial aerial studies conducted with input from Pikwàkanagàn show thinning moose populations across the Ottawa Valley reflect a broader decline in Ontario. This drop in numbers has been associated with climate-driven habitat loss, overharvesting and industrial sprawl such as logging, according to a 2022 study published in Ecology and Society.

Mike Diabo, a member of the moose committee from Kitigan Zibi, said consultation with Anishinaabe communities to learn about the changes hunters have seen on the land during their lifetimes have lead the committee to attribute moose decline to similar factors.

The committee gathered this knowledge through consultation with Anishinaabe communities to learn about the changes they have seen on the land during their lifetimes and how it is impacting moose populations.

“We were tasked with doing something and to act on behalf of these animals, something that came from my elders that saw this happening, and then to raise the alarm,” Diabo said.

Anishinaabe communities gather to share their knowledge of the moose among each other so they can work to combat population declines. [Photo by Marie-Raphaëlle Lebond provided by the Anishinaabe Moose Committee]

Importance of 'weaving' Indigenous knowledge

Merv and Barry Sarazin said they’ve noticed a change in the moose population during their lifetimes, which they attribute to climate change overhunting and deforestation in the park. While growing up in Pikwàkanagàn, the brothers would routinely get up before sunrise on crisp fall mornings and travel to Algonquin Park to hunt.

For Barry, now an elder on Pikwàkanagàn, the hunting season always starts with an Anishinaabemowin moose song to thank the moose for offering its spirit.

As the sun rises over the trees, Merv says he lets out his best moose call, mimicking the sounds the animal makes when attracting a mate, to bring them closer. He then sits back and patiently waits for them to answer.

However, warming climates mean hunters must navigate earlier and unpredictable mating seasons while moose travel further to find wetlands and shade to cool down. If hunting seasons are too inconsistent, Merv said moose don’t always answer his calls.

“They’re not coming at a call,” Merv said.

During the first phase of the moose committee’s study, members held consultations in several Anishinaabeg communities to gather witness statements from hunters. Diabo said prioritizing Indigenous knowledge, such as observations from people on the land, is important to explain trends behind the moose decline numbers.

“You have generation after generation of families that have witnessed this movement and participated in harvesting practices and … coexisting with the herd. You recognize pretty quickly when things are not right,” Diabo said.

Pauline Priadka is one of many Western scientists turning to Indigenous teachings to inform moose population research. As a wildlife engagement specialist, her PhD research at Laurentian University worked on embracing inclusive approaches and weaving knowledge systems to offer a holistic understanding of factors affecting moose.

Western science often focuses on habitat disturbance and predation on moose, she said, while Anishinaabe knowledge emphasizes harvest pressure, winter onset and timing of mating season.

“It helps in getting a bigger picture and opening the door to topics that maybe aren’t thought of from a Western science perspective,” she said. “For the most part, cumulative effects can be really hard to identify on paper.”

A stretched out moose hide sits behind a shop on Pikwàkanagàn First Nation. Community members aim to use all parts of the moose and not waste any of it. [Photo by Madison Flaro]

Looking ahead

Moving into the next phases of the moose committee’s initiatives, Chief said work is underway to help “communities take part in the studies and be part of the research.”

To help transfer knowledge between hunters and younger generations, the committee is developing a toolkit and an encrypted app called Our Data Indigenous for land users to track and share moose patterns. The app uses satellite data to geo-locate videos and photos uploaded by users.

“People that have that experience are out there all the time and see this information. They see it in real time, they see patterns change, see behaviour change. They see something that’s not normal right away. That observational data is really important,” Diabo said.

As moose hunters from Pikwàkanagàn look to pass their knowledge to the next generation, Kohoko said Pikwàkanagàn’s involvement in the committee gives him optimism that the community is beginning to pay attention.

“This is something I would never imagine in my lifetime, to be on a committee to represent and just share the thoughts of what we see out of our eyes is totally amazing to me,” Kohoko said.

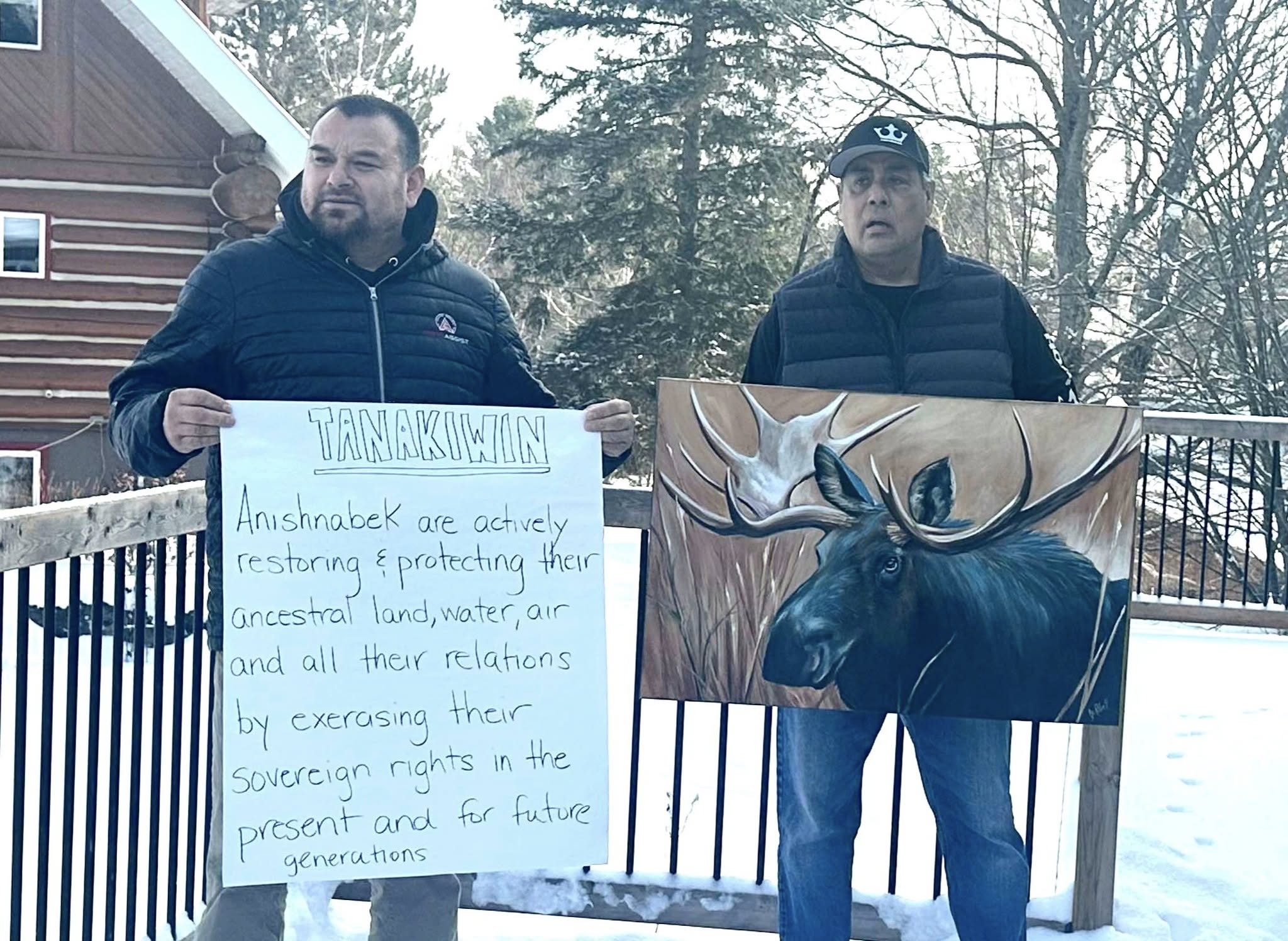

Mike Diabo and John Paul Kohoko meet as part of the Anishinaabe Moose Committee to share traditional knowledge of the moose among communities. [Photo provided by the Anishinaabe Moose Committee]