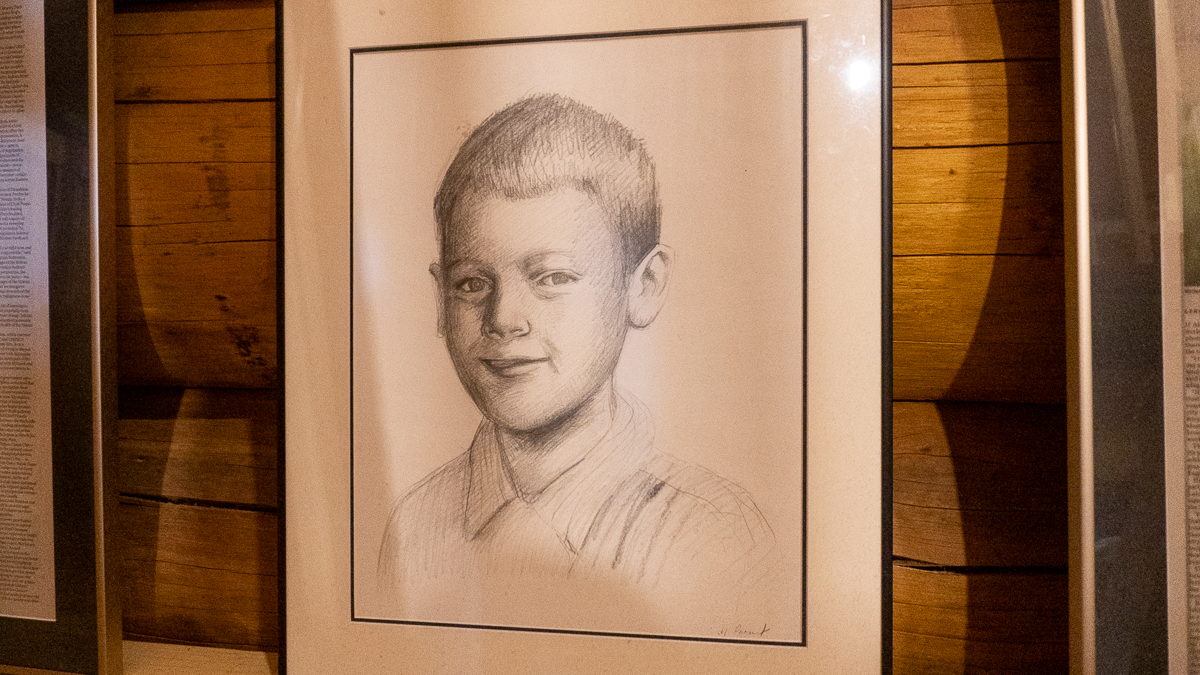

Albert Dumont, an activist, spiritual advisor and writer from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, has consistently fought for human rights and environmental protections in Ottawa. [Photo © Olivia Grandy]

“A tree has rights”: Albert Dumont’s fight to protect land

In hospitals, prison harmony circles and on city streets, Albert Dumont has spent decades fighting for what he believes in – the rights of people and the environment.

By: Olivia Grandy, Reagan Spencer, Jasmine Birks and Ley Pickard

Albert Dumont’s activism career began when he fell off of a four-story building.

At the age of 40, he suffered two crushed vertebrae and two cracked ones. Three years after the accident, he began spending time with chronically ill patients. He soon met Mike Cornel, who experienced a similar fall that left him paralyzed.

Dumont said he advocated for Cornel, a Cree man, who often faced racist remarks from healthcare workers.

Albert Dumont, an activist, spiritual advisor and writer from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, has consistently fought for human rights and environmental protections in Ottawa. [Photo © Olivia Grandy]

Thus began his 30-year career as an activist, storyteller, poet, playwright and spiritual guide.

Dumont describes himself as a human rights activist, but that extends to the natural world. “All these things in the forest, they have rights,” he said.

Over the past two decades, Dumont has stood side-by-side with Ottawa’s environmental activist community. He’s fought projects such as the Zibi and Tewin housing developments and the new Ottawa Civic Hospital campus, which have plowed ahead on what Dumont describes as Algonquin ceremonial lands.

His presence and speeches have become familiar at protest sites across the city.

“Does the world need more condos, or does it need more sacred sites to be revived, to help the health of water and winds?” Dumont asked while sitting in his log home in the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation.

Dumont picks out tea at his kitchen counter in his home at Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation. He says that, even as a child, he felt strongly about protecting the environment. [Photo © Olivia Grandy]

The Making of an Activist

Dumont grew up in the only Indigenous family in the mining town of Pontiac, Quebec. He said a racist attack from his teacher when he was ten-years-old ignited his passion for human rights.

As Dumont remembers, his teacher told the class they needed to know the Bible to go to heaven. When Dumont asked about his ancestors, she responded, “Your ancestors are in hell.”

“If my ancestors are in hell, then I want to go to hell someday,” Dumont replied.

“That’s why I’m who I am today,” he said while enjoying tea and strawberry rhubarb pie at his kitchen table.

That catalytic moment became a scene in his one-man play Bloodline, which he wrote and performed.

Dumont picks out tea at his kitchen counter in his home at Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation. He says that, even as a child, he felt strongly about protecting the environment. [Photo © Olivia Grandy]

Bloodline outlines his family’s oppression under the Indian Act. Dumont believes that paternalistic government policies planted the seeds for his years-long battle with alcoholism.

“In 1988, I renounced alcohol as a cancer that was eating at me spiritually,” Dumont said about his recovery. He simultaneously embraced Indigenous spirituality.

After his back injury, Dumont immersed himself in activism, beginning with protesting for Indigenous victims of crime, leading him to work as a harmony circle leader at the high-security Millhaven Prison.

As he was walking barefoot with a Cree prisoner who hadn’t set foot on grass in seven years, Dumont’s activism work, not just to protect people but also nature, had only just begun.

The Rights of Nature

In the last fifteen years, urban land developers building on unceded Algonquin Anishinaabe territory without proper consultation has become a repeated pattern, said Dumont.

From fighting for the South March Highlands in 2011 to being one of the loudest opponents to the Zibi housing development along the Akikodjiwan or Chaudière Falls, Dumont said his philosophy is rooted in “just being there to be counted.”

Ottawa’s Chaudière Falls are a sacred Algonquin ceremonial site. Now, the small space is occupied by condos built as a part of the Zibi development.

Dumont and other activists fought four years to keep the islands as a space for gathering. Their work was ultimately unsuccessful.

“When you’re an activist fighting to preserve the environment and you’re up against what they call ‘the almighty dollar,’ you don’t win very often,” he said.

Dumont standing on the front porch of his log home in the winter. [Photo © Olivia Grandy]

He also opposed clear-cutting to make way for a parking garage at the new Ottawa Civic Hospital. He advocated against the Tewin development, a controversial housing project being built on unceded Algonquin land along Ottawa’s Greenbelt. It has garnered both support and dissent from nearby Algonquin groups.

Dumont emphasizes that protecting future generations is what motivates him.

“I need to be at peace in knowing that at least I tried,” he said.

Dumont’s sister, Cecile Dumont, praises her brother’s commitment to his community, spirituality and activism.

“Albert’s wisdom, his dedication to Indigenous people and his example are an inspiration to everyone who knows him,” wrote Cecile, who participated in a number of protests alongside her brother.

Dumont says his activism came naturally to him and has given his life purpose. [Photo © Olivia Grandy]

Making a Stand for Future Bloodlines

Chris White, a friend of Dumont’s and a fellow activist in Ottawa, said that when he became involved in protecting began lobbying to protect historic trees at the Civic Hospital site, Dumont was quick to lend his support.

“I called on Albert, and he showed up even in the middle of winter and freezing cold. He showed up and addressed people and helped us all to understand why it was so important, specifically to protect trees in particular,” said White.

Dumont has been involved with a number of different causes, including this Every Child Matters march in September 2022. He says what motivates him is future generations. [Photo © Christopher Dunn]

Dumont said the reason he protests is for future generations.

“I feel badly for the human beings in the future because this generation, my generation, has a lot to do with the pollution and the destruction, wiping out of forest, and who’s going to really suffer for that is … future generations,” said Dumont.

Dumont advises young people who want to be environmental activists to begin with reflection.

“I just ask them to sit back once a week, or whatever they want, and think about the future. Are they willing to accept the further abuse of this poor planet, or will they make a stand to defend it and fight against those who don’t care?”