![Isaruit Inuit Arts community members line up for a feast of country food, home-cooked desserts and fruits and vegetables available at Friday weekly drop-ins. [Photo © Grace Huntley] At a community centre, people stand in line at weekly drop in to get food](https://capitalcurrent.ca/indigenous-communities/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Photo-1edit.jpg)

Inuit living in Ottawa line up for a feast of country food, home-cooked desserts and fruits and vegetables at a weekly drop-in hosted by Isaruit Inuit Arts in the city‘s east end. [Photo © Grace Huntley]

‘A visceral way of connecting with your culture’: How Isaruit Inuit Arts brings country food to urban Inuit in Ottawa

For Ottawa’s urban Inuit, weekly drop-in meals at Isaruit Inuit Arts are a taste of home in the south

By: Jessica Campbell, Ryan Clark, Grace Huntley, and Bianca McKeown

In a kitchen tucked away in the basement of the former Rideau High School in Ottawa’s east end, Aija Komangapik stands next to a simmering pot of honey garlic seal ribs.

Other members of the capital’s large Inuit community venture in and out of the kitchen, speaking in both English and Inuktitut as they prepare a feast of country food — wild game from the North such as seal, Arctic char and caribou, which have been part of the Inuit diet since time immemorial.

“I focus really hard on showing, especially with this seal meat; it’s very easy to transform,” Komangapik says, explaining she likes to get creative with the country food recipes that she shares at the centre, making seal blood cake and cookies.

It’s a typical Friday at Isaruit Inuit Arts, a gathering place for urban Inuit to sew, create artwork or just chat. Once a week, Isaruit throws its doors open to host a drop-in meal. For Inuit living in Ottawa, thousands of kilometres from their home communities, these country food feasts are about more than sustenance — they’re a way to stay connected with their culture.

“It’s like any other group of people; being able to eat your own food is a pillar of culture. Food is your fuel… the way that you procure it, the way that you cook it, the way that you handle this animal, all of it bakes into culture — pun intended,” Komangapik says.

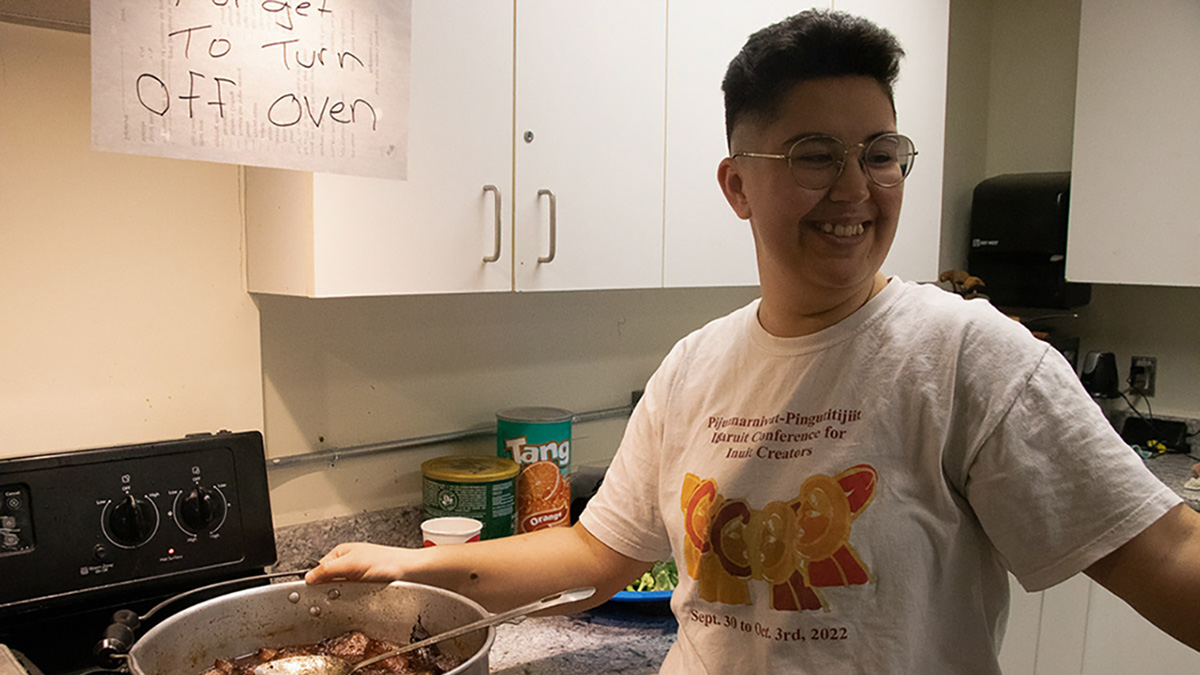

Aija Komangapik makes honey garlic seal ribs at a weekly drop-in. She says she likes to demonstrate the versatility of seal meat with her recipes. [Photo © Grace Huntley]

Ottawa’s Inuit population is estimated to be upwards of 6,000, the largest outside the North. Many Inuit come down south for the cheaper cost of living, employment opportunities and to pursue higher education. However, living in a new city can be very isolating and community spaces like Isaruit are vital for Inuit to connect with their culture and hang out — all without having to pay.

“Everything about Ottawa is very … you have to give, give, give, give,” says Komangapik. “[At Isaruit], you don’t have to give; you can just be you.”

Feeding the city

Just getting food to Ottawa for the drop-ins is a community effort, with some food donated and the rest purchased by Isaruit.

“That’s how it’s meant to be. That’s how Inuit share their food,” says David Erkloo, an Elder and workshop instructor at Isaruit. “If I have polar bear meat then I will bring [it] here; [or] maktaaq, which is narwhal skin.”

Komangapik, an artist and hunter from Iqaluit, is proud of the seals she has hunted on trips with her dad. Her father, Ruben, co-owns Reconseal Inuksiuti, a company that hunts seals in the Magdalen Islands to avoid overhunting seals in the North, which experiences food insecurity. Komangapik emphasizes the value of knowing where your food comes from.

“I remember the coat on it was very speckly on the bottom, and it had a little scratch that tells me when it was younger it was attacked by something, probably a great white shark,” she says of a seal she hunted on a recent expedition.

It’s a long trek to get to the islands — an 18-hour drive plus five hours by ferry. Komangapik makes the trip a couple of times a year. After a seal is shot, Komangapik skins, butchers and freezes the meat and sends it off to Inuit across Quebec and Ontario, including Isaruit.

“Everything is very fresh,” she says. “Sending it to the centre is important because we’re able to give to inner-city Inuit the meat that they really crave.”

Being able to eat your own food is a pillar of culture. The way that you procure it, the way that you cook it, the way that you handle this animal, all of it bakes into culture — pun intended.

David Erkloo holds a replica paddle of a qajaq, or kayak, which he made. [Photo © Jessica Campbell]

Other foods are shipped south by relatives in the north.

Canadian North, the main airline connecting northern and southern Canada, provides a discount on country food shipments, charging $1.31 per kilogram. Erkloo typically pays $8 per shipment, receiving the meat free from his family.

“Country food, we like it and it’s good for you; healthy,” he says. “Down south food is greasy, and sometimes spicy and all the bad things.”

While getting country food to Ottawa can be a lengthy and sometimes challenging process, it’s nutritious and has numerous health benefits.

Nat Whalen, a registered dietician and a community nutrition specialist for the Government of Nunavut, says research shows that regular country food consumers have higher intakes of key nutrients like vitamins A, B 12, C, D, iron, zinc and omega-3 fatty acids that help keep the body strong and the mind sharp.

“Country food is a complete diet, and Inuit have been well-nourished by a traditional diet for thousands of years,” says Whalen.

A community member rips a piece of Arctic char into smaller pieces after cutting it with an ulu. [Photo © Grace Huntley]

A woman holds up a piece of cut Arctic char. Beside her, community members use traditional knives known as ulu to cut fish and maktaaq. [Photo © Grace Huntley]

A culture of sharing

Inside the repurposed classroom that serves as Isaruit’s main gathering space, steaming seal soup, fried bannock and freshly baked sweets are set out on a table buffet-style. As the drop-in begins, Elders congregate at a long wooden table and share hunting stories from back home in Inuktitut, while others line up for food and catch up over a bowl of soup.

Today, the room is packed, with around 20 people seated across various tables, eating under the maps of the North posted on the classroom walls.

A frequent guest at the drop-ins is Zorga Qaunaq, an artist and actor. She says country food brings people together. Growing up in Ottawa, some of her only experiences eating country food were when her mom took her to cultural events. Now, with Isaruit’s drop-ins, she feels connected to the community.

“It’s part of our culture to eat that way. It’s a lot of sharing stories and sharing food and sometimes sharing emotions,” she says. “It’s just such a visceral way of connecting with your culture and your people — plus, it’s super nutritious.”

Komangapik says free community spaces are disappearing in the rest of the city, but Isaruit is expanding. A new seal skinning room is currently in the works. The room will be used for the removal of fat and skin layers from seals, as well as drying and tanning the fur.

“I want to have this room because I don’t see very many people making maktaaq anymore, especially in the south. It’s very hard, especially for a landlocked community, to really access anything to do with the ocean,” says Komangapik, adding she hopes the skinning room helps foster an interest in learning the skill.

“No one else knows how to do it the way we do it, and it should be prized and valued and put on a really high pedestal.”

Komangapik says she’s never seen another organization in Ottawa dedicate space or budget to a room like this one. It’s emblematic of what Isaruit is trying to create for Inuit in the city.

“[At Isaruit] you’re allowed to be present and you’re allowed to eat food, which is the making of a community.”

*This story first appeared in Canada Geographic in partnership with the Reporting in Indigenous Communities course at Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication.