![]() No One Is Illegal Vancouver Coast Salish Territories, Justicia for Migrant Workers, and Philippine Women Centre organized a flash mob on Dec. 18, 2011 for International Migrants’ Day. [Photo © Caelie_Frampton on Flickr]

No One Is Illegal Vancouver Coast Salish Territories, Justicia for Migrant Workers, and Philippine Women Centre organized a flash mob on Dec. 18, 2011 for International Migrants’ Day. [Photo © Caelie_Frampton on Flickr]

By Allison McNeely

OTTAWA — New rules coming into effect next year for the caregiver immigration program do not fully address abuses within the system and will make it harder for temporary workers to stay in Canada, says an Ottawa temporary workers advocacy group.

“The changes are geared more toward restricting access to permanent residency,” says Aimee Beboso, chair of the Philippine Migrants Society of Canada.

New immigration rules

Citizenship and Immigration Minister Chris Alexander announced in October plans to overhaul the live-in caregivers program. It will be split into two streams of workers, child care and health care, starting in 2015. Permanent residency granted through the program will be capped at 5,500 people per year. Child-care workers will make up 2,750 of that total. Currently there is no cap on permanent residency granted under the program.

Alexander also said the government would process half of the current 60,000-case backlog of permanent residency applications within six months next year. So far in 2014, 17,000 temporary workers have been granted the right to stay in Canada after completing their two-year work contract. Many of these workers have likely been in the country longer than two years because of the wait time to receive their permanent residency.

David Harty, a Citizenship and Immigration Canada spokesman, said in an email that these changes are intended to eliminate opportunities for abuse and reunite temporary workers with their families left in their home country.

“Serious concerns about the long periods of family separation faced by many workers in the program, the vulnerability of caregivers living in the homes of employers, and the need to improve the long‑term outcomes of former caregivers in the Canadian labour market cannot be ignored,” he said.

Increase access to permanent residency, advocates say

However, Beboso says that these changes do not truly address “vulnerability and the precarious nature of the work.”

Workers admitted under the caregiver program should automatically receive permanent residency because it gives them access to the same rights as ordinary workers in Canada, such as the ability to bring their families with them and the ability to move between employers, she said.

“If they’re good enough to work in this country they deserve rights in this country,” she said.

Beboso said she is concerned that the government has not given any commitment on how long it will take to actually make a decision on each application despite its commitment to process permanent residency application backlog within six months.

“It’s a very creative way of making an announcement,” she said. “It’s not a given. They still have to make individual assessments.”

Aimee Beboso with Garry Martinez, chairperson of Migrante International, an organization that works to protect the rights of Filipinos abroad.

The average worker affiliated with her organization is generally in Canada for five to seven years before they get permanent residency, including the time they spend working under a temporary foreign worker program. She said the new six-month rule does not actually guarantee that the wait time for permanent residency will be shortened because the government has not committed to a timeline for making a decision on each application in the backlog.

Reforms don’t address abuses

Beboso also said that the removal of the live-in requirement under the program is not entirely good news. The program still gives the employer the right to ask their employee to live in the home. The government says the arrangement allows for abuses that are like “modern slavery” to occur.

“If they’re good enough to work in this country they deserve rights in this country.”

The overhaul of the caregiver program also does not address concerns about unpaid overtime or employers asking workers to perform duties outside their government-mandated contract, she said.

“Washing your car and gardening is not care work. Washing the windows outside is not care work,” Beboso said.

Live-in caregivers are tied to one employer for their two-year term and it can be difficult to get away from an abusive employer because there are no set timelines for processing a new work permit for a new employer, Beboso said. Workers have no guarantee about when they will get a new labour market assessment that shows the need for a caregiver and the subsequent work permit.

“In that kind of relationship the upper hand is always with the employer,” Beboso said.

Much of her organization’s work centres on holding workshops to inform workers of their rights under the program and their options to immigrate. Working at minimum wage, she said most workers can’t afford to hire a lawyer if their case gets “complicated.”

No legal assistance

Calls to Ottawa immigration law firms reveal caregivers are most likely not accessing legal services during their permanent residency application.

Tamara Mosher-Kuczer, an associate at Ottawa’s largest immigration law firm Capelle Kane, said her firm did not handle many caregiver cases and they would not be the best firm to speak on the subject. She suggested calling lawyers in Vancouver and Calgary.

“Washing your car and gardening is not care work. Washing the windows outside is not care work.”

Ronalee Carey, an independent immigration lawyer, said if Capelle Kane wasn’t handling caregiver cases, then it was unlikely any firms in Ottawa were getting these kinds of clients. She suggested calling lawyers in Toronto.

“Maybe these women are fighting through it on their own,” Carey said.

Carey said she had recently given a consultation on a permanent residency application filed incorrectly under the live-in caregiver program. She said the applicant was “screwed” because they had filed to the wrong immigration office and, because of their low wages, could not even afford her services. Carey referred the worker to a colleague who runs a community legal clinic for assistance filing as a humanitarian applicant.

The Philippine Migrants Society of Canada has partnered with the University of Ottawa legal clinic in the past to offer its members free legal advice, since temporary workers do not qualify for legal aid. Beboso said she hopes to develop more permanent relationships with lawyers and law students to help her members, as the Montreal and Toronto chapters of the society have done.

Beboso said she wants to develop these relationships because she anticipates the demand for legal advice will only increase once deportations under the new rules begin in April 2015.

“We may have to represent people who are illegally staying in Canada because of the changes,” she said.

“We don’t have access to lawyers right now.”

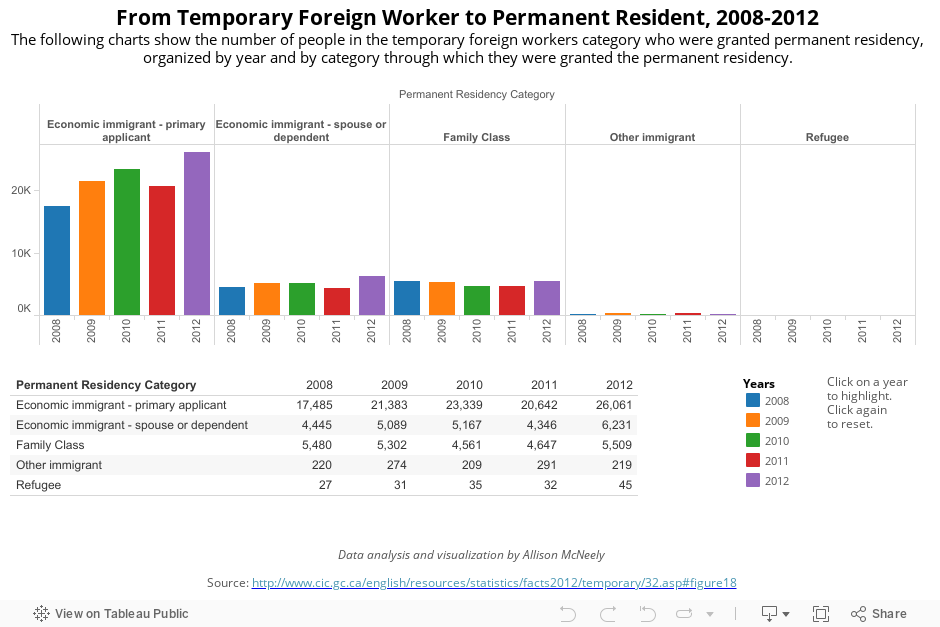

Thousands of immigrants come to Canada each year through the federal temporary foreign worker program. However, not all of them obtain their permanent residency as an economic immigrant. This data visualization shows how many temporary foreign workers obtain permanent residency under each immigration program.