Abandoned barn stands amidst the landscape of land acquired by Pikwàkanagàn’s LP. As the community deliberates on its final purpose, the fee simple land brings available equity within the community. [Photo © Madeleine Van Clieaf]

Waiting for land back, Pikwàkanagàn First Nation is opting to buy back

Through land acquisitions and innovative partnerships, the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation aim to break free from the Indian Act and carve out a path towards sustainable growth and community development.

By Ally Lemieux Fanset, Madeleine Van Clieaf, Maude Lipsett, and Sophia Foglia

Published in The Globe and Mail

By the cool water of the Bonnechere River, obscured by bush and an abandoned barn, a plot of land stretches out across 170 acres. To some it’s just an empty lot with maple trees, but to the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation (AOPFN), the land represents an investment in the community’s economic future and self-determination.

Their reserve lies west of Ottawa, near Renfrew County, though their unceded land stretches nine million acres including eastern Ontario and the National Capital Region. For generations, they were restrained to 1800 acres of rocky unfarmable reserve land. The newly purchased land is part of the Nation’s plan to develop beyond the reserve’s borders.

With round glasses and a wide smile, recently elected councillor Don Bilodeau previously led the economic project responsible for developing the economy off-reserve.

Councillor Don Bilodeau of the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation poses in front of the band office. [Photo © Madeleine Van Clieaf]

“This land is very rich in many ways and beautiful,” said Bilodeau. “Yet we watch all that’s happening around us and none of it comes back this way. It’s a struggle for anyone to give us more. So, we have to buy back the land that we once were the stewards of a couple of hundred years ago.”

Under the Indian Act, community members are unable to own reserve land, as it’s owned by the Crown. The new purchase lets the community sidestep the Indian Act by owning land and choosing how to use it. Yet, the land’s future is uncertain and a controversial path forward for many.

Limited Partnership

In 2020, AOPFN bought two parcels of land through their Limited Partnership (LP). Council plans on adding one parcel to the reserve. The other lies five minutes away and could be kept “fee simple.”

Unlike reserve land, fee simple means Pikwàkanagàn’s Limited Partnership has exclusive rights and ownership to the property, aside from taxation, debt obligations and local building restrictions.

1m12s: “Gain a clear understanding of fee simple land ownership and its implications within Indigenous rights and land management, shedding light on important aspects of land tenure in Indigenous communities.” [Filming © Maude Lipsett; Editing © Ally Lemieux Fanset and Maude Lipsett]

“With the investment in land, we might be able to have some bank equity, some collateral we can borrow against to invest and grow capital, trying to be smarter and skirt around the Indian Act,” Bilodeau explained.

The purchase is a small piece of a larger venture: the AOPFN Limited Partnership, a company run in partnership with the community.

From her yurt in Pikwàkanagàn, Leah Hinterberger took the helm of the LP last year. She hopes to generate enough revenue to support local businesses, education and youth engagement.

Aligning with her passion for the environment, the LP is partnering with renewable energy businesses. Generated funds go back to the shareholders, the AOPFN. But Hinterberger has big aspirations.

At the Environmental Field School near Fort-Coulonge, Leah Hinterberger proudly holds a lake sturgeon, an endangered species within the Great Lakes and Upper St. Lawrence. There are many preservation efforts ongoing across the province of Ontario. [Photo provided by Leah Hinterberger]

“The LP has been small. I want to take it to the next level and really start bringing in some funds,” she said.

The company serves to help prove self-determination for ongoing land claim negotiations, Bilodeau explained. He sees the land as just a small part of the economic development created by the Limited Partnership.

“Our ability to foster partnerships and joint ventures with numerous businesses that are active in that nine-million-acre territory is really something we feel is possible,” Bilodeau said. “The limited partnership, from our perspective, is something that can earn revenue long term for the First Nations.”

Land back, not buy back

Veldon Coburn, a political science professor at McGill University and member of AOPFN, said he has mixed feelings about the purchase.

“We’re buying back our own land, which is a little bit perverse,” said Coburn. “We’re paying the fee to give us our land back, to give us back what was already ours.”

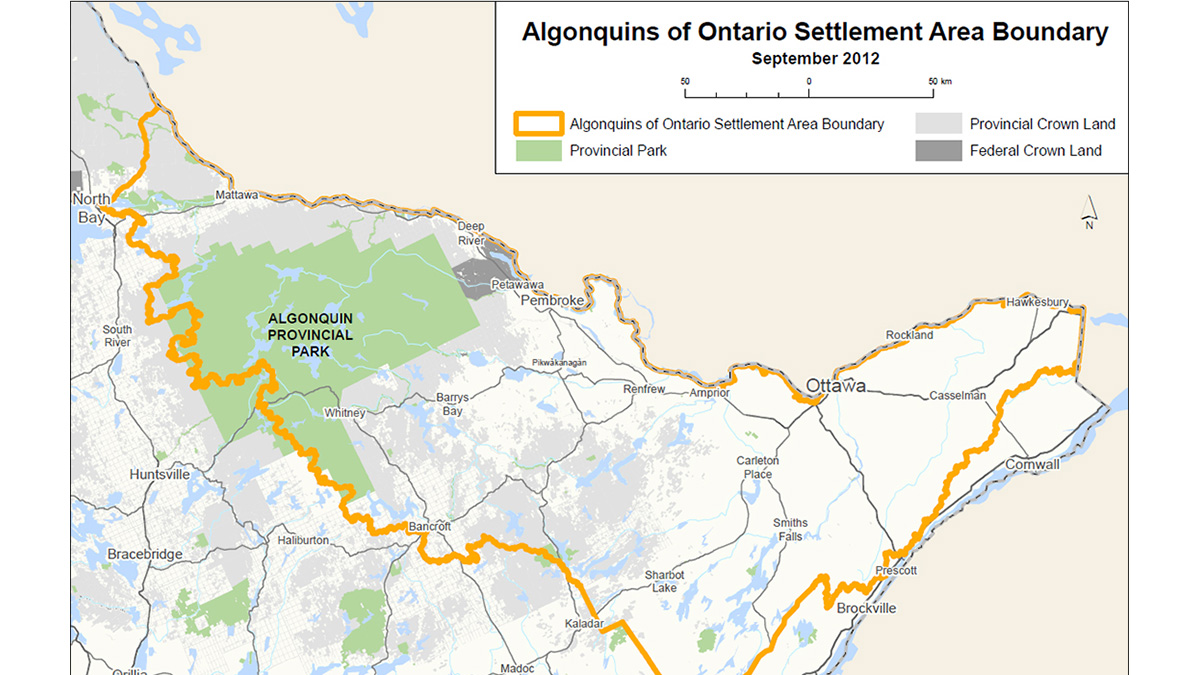

Currently, 36 000 square kilometers of Algonquin unceded territory in Ontario is involved in a land claim over 30 years old. As the only Algonquin reserve in Ontario, Pikwàkanagàn, stands as an important community in the process.

“We were left with something that was woefully inadequate to begin with, and we’re still playing catch up in terms of expanding into something that would be suitable for our needs,” Coburn said.

The Algonquin claim encompasses 8.9 million acres (36,000 km²), spanning across the majority of eastern Ontario. Within this claim area includes Algonquin Park and the City of Ottawa. September, 2012. [Photo © Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Government of Canada.]

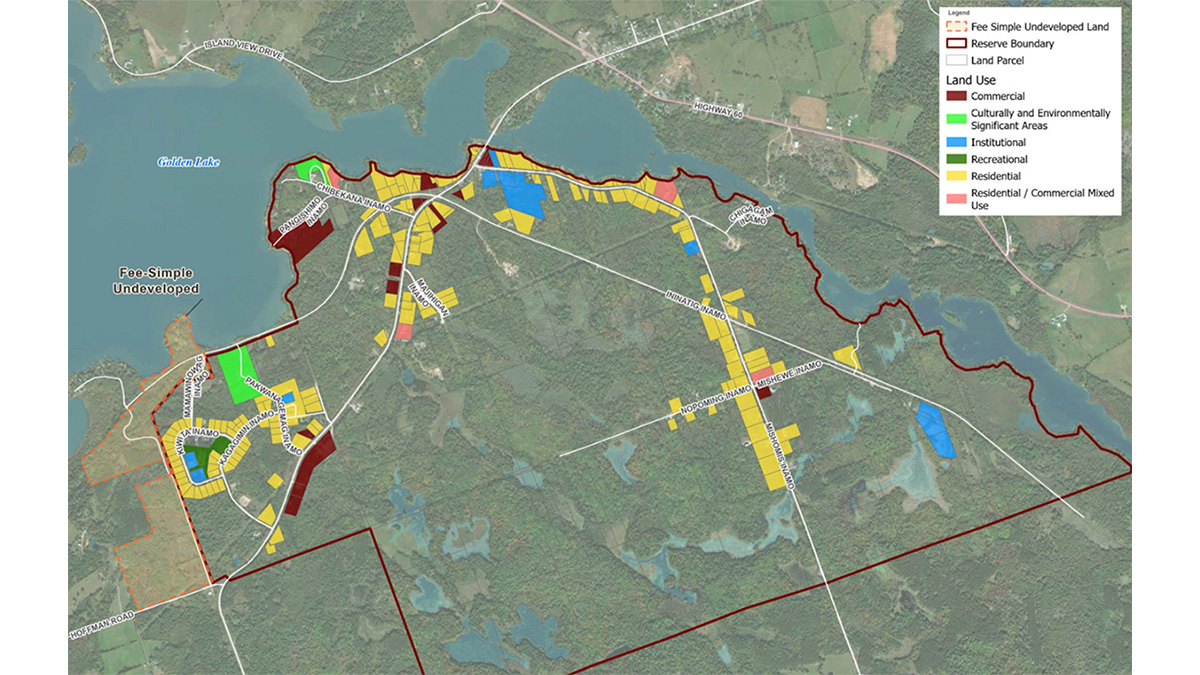

Existing land and current uses map from AOPFN’s Land Use Plan. August, 2022. [Photo © Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation.]

A vision for the new land

The AOPFN Council hasn’t decided on the land’s future, and community members are divided on how to use it. The Nation is dealing with multiple crises, including housing, health, and food insecurity.

Last December, the community declared a state of emergency for an opioid crisis.

In December 2023, the Alonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation declared a state of emergency after a series of opioid related deaths. The flag is half mast to mourn the loss of a community member. [Photo © Maude Lipsett]

If they don’t use the land for economic development, Bilodeau said they could use the fee simple land to build a treatment center or incentivize doctors to move nearby.

For others, housing is a key issue.

Ryan Peters works the front desk at the Makwa Community Centre and struggled to find housing after finishing college. He said the new land could be a solution.

“It might be good for other people who are looking to come back as well,” Peters said. “If they had housing set up for people to come back and to rent or buy.”

There’s an economic bonus to building new housing on fee simple land – homes on reserve land can’t be used as collateral to get a loan, Bilodeau explained, but you can borrow against fee simple land.

The farm house is located on the plot of fee simple land. Councillor Bilodeau imagines that the farm house could be transformed into a space for rehabilitation or for a doctor to reside in to address the ongoing crisis. [Photo © Madeleine Van Clieaf]

“If my roof needs to be repaired, I have to use cash. The banks won’t loan me money because my house doesn’t have value in their eyes,” explained Bilodeau, giving an example of some member’s experiences.

For Bilodeau, the community has to expand beyond the land currently available, through land claims and buying back.

“We need to invest beyond what’s available now because it’s not good enough. We want to do more for our community in the long term for our youth. That’s our long-term plan to be more self-sustainable and support self-governance,” Bilodeau said.

The Pikwàkanagàn reserve resides on the Bonnechere river. [Photo © Madeleine Van Clieaf]