Food price inflation is certainly a top of mind issue for consumers. But for restaurant owners, it’s putting even more unwanted pressure on their future, a Capital Current survey has found.

Mark Steele, owner and chef of OCCO Kitchen in Ottawa, knows all about this problem. He has been in the restaurant industry for 30 years. He’s always been forced to be innovative with his menu to keep his prices affordable. But this current period of price inflation has been a trial.

“The hardest part right now,” he says, “is just navigating all the price fluctuations and increased prices.”

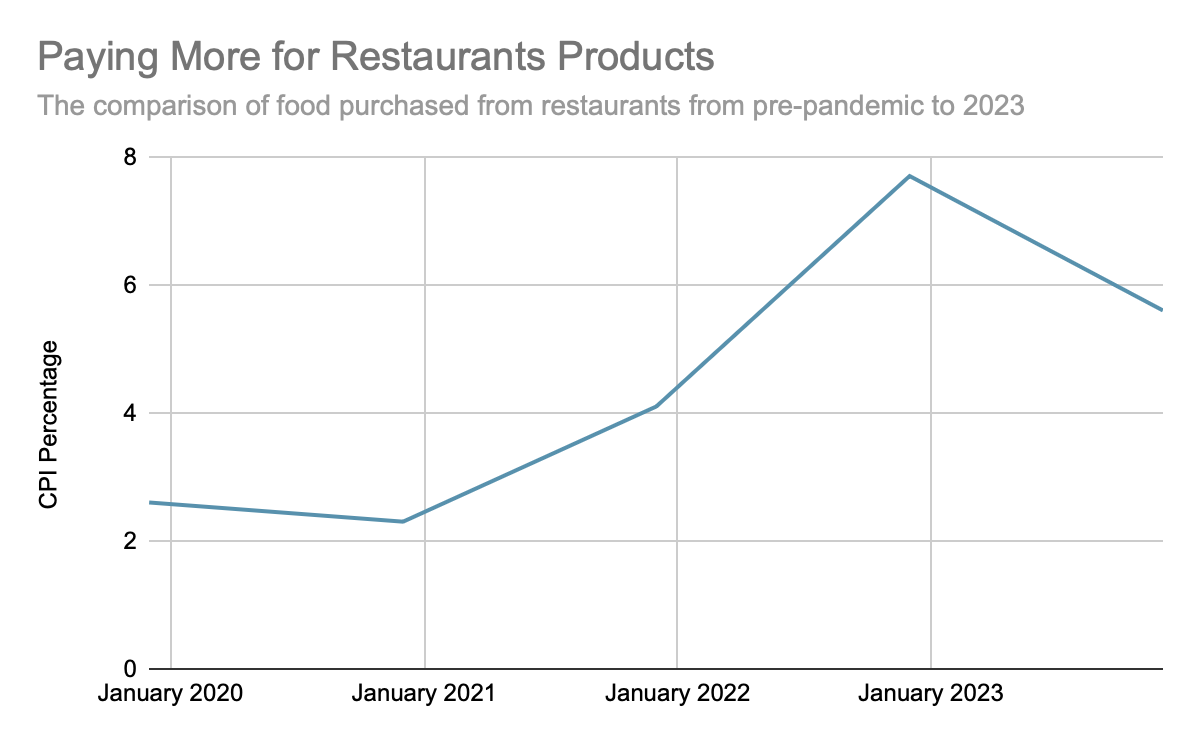

He’s not alone. Food purchased from restaurants has increased 4.4 per cent from before the pandemic to December 2023. This is a three per cent price difference, according to an analysis of Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Chris Elliot, Restaurants Canada’s lead economist and vice president of research, says menu prices increased to 6.5 per cent in 2023. This increase “was largely due to higher costs for cooking oil, protein, labor costs, insurance costs and rent,” he said.

That’s about to ease. Elliot says Restaurants Canada expects menu prices to be down about 1.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2024.

Despite this slight decrease in menu prices, they continue to affect people’s choices in where, when, and what they eat. And for an industry that already struggles with narrow profit margins, that’s not good news.

Jennifer Areli, a single mother of two boys, has been eating at restaurants less since prices have risen. At the beginning of the pandemic she liked supporting local eateries because she knew the businesses were struggling, but spending $75 for her family or $40 for herself to eat out has become too costly.

“And that doesn’t include a fancy drink,” she said.

She sticks to pizza and cheese bread now when the family eats out.

“Going to a restaurant is more of a treat thing for us, it’s not something we can do every week.”

The price increase hasn’t deterred everyone.

Emma Kaye, who works at Algonquin College in food services, said she doesn’t consider the prices to be an issue. She said she knows the prices are going up for everybody in multiple industries, so she finds it does not affect her choices much.

She has continued to support local restaurants since the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the prices are higher, she understands that part of the increase comes from paying their employees fair wages.

As for Steele, he’s trying to adapt to the growing cost of products.

He understands why many restaurants resort to “shrinkflation”, a practice in which restaurants will cut down portion sizes while menu prices are fixed. Steele refuses to do that and prefers to change the product altogether.

“If we are using kale for our salad and the price goes through the roof, then I’ll design a new salad, maybe using romaine lettuce if the price is good,” Steele said.

According to Steele, the national average for profit margins is roughly four per cent right now. This means that if a restaurant were to sell $100 worth of food, it would only make $4 profit, which can easily be lost by accidentally over-booking staff or having an excess amount of waste one day.

“It’s tough – it is tough. I mean our profit margin is pretty much zero, you know? And it’s just too hard to navigate. Restaurants already have extremely slim profit margin,” Steele said.

Although frustrated, Steele is embracing the creative process of modifying his menu as prices fluctuate.

“At the end of the day, people want to be social and get out and so I think the demand is always going to be there,” Steele said.