Ottawa-based mother-artist collective 44.4 unveiled their first exhibition Nobody Sees a Flower at the Ottawa Art Gallery (OAG) on March 1.

Scattered across three floors of gallery space, the collection explores the intersection and complexities of motherhood and art, drawing inspiration from the observation of American modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe: “Nobody sees a flower, really; it is so small.”

“It reminded us of the mostly unseen cognitive labour that mothers inherit,” said Alexa Mazzarello, member of 44.4 collective.

The roots of the collective trace back to 2014 when O’Keeffe’s painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1 sold for $44.4 million (U.S.), making it the most expensive work by a female artist ever sold at auction.

Sexism in the art world has make it harder for women to succeed. Female artists face increasingly unequal compensation for their work: there is a nearly 48 per cent discount for women’s art at auction in the United States. Additionally, female artists between the ages of 55–64 earn 66 cents for every dollar earned by their male counterparts.

The 44.4 collective, composed of 11 members including Jennifer Cherniack, has challenged stereotypes surrounding the concept of a “mother artist.”

With years of experience in the contemporary art scene, Cherniack initially viewed the term mother-artist as a “dirty word.”

“All of the internalized misogyny that has been passed on to me lived within me and percolated,” she said. “I thought ‘this is contemporary art, and this is motherhood – never the two shall meet’.”

Through encouragement to create from fellow female artists and mothers, Cherniack’s inspiration to create was rekindled. Being part of the collective “ignited” something in her and brought a newfound “joyfulness” to her practice.

“I’ve shed something,” she said. “This idea of being a mother-artist is no longer shameful. I see the intersection – I am a parent, and I am an artist … there can be more truth than one truth.”

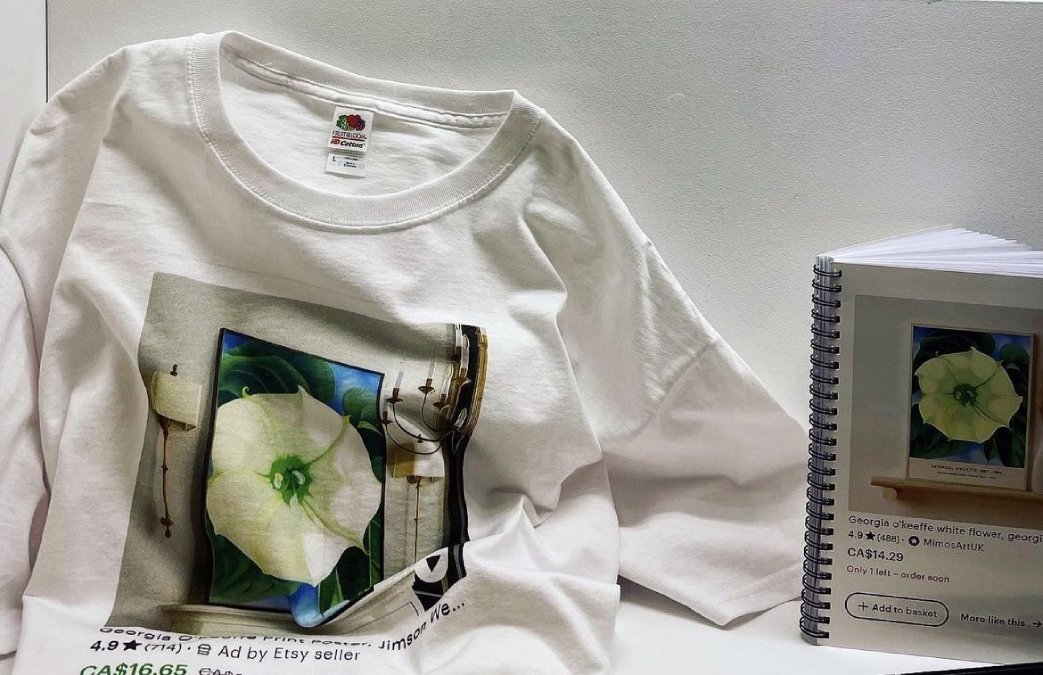

Riffing off of museum gift shop swag, Cherniack’s work explores the widespread consumption of art through reproduction.

Using image searches of O’Keeffe’s painting as a stand-in for the work itself, her project speaks to the impact of digital reproductions and commercialized representations on the true essence of art – much like the exhibit title, nobody sees the actual painting.

“It’s been a completely art, life and career-changing instance in my life,” she said. “I’m an artist again.”

Mazzarello, a photographer, joined the 44.4 collective, driven by the desire for a supportive community that resonated with her experiences and artistic vision.

Despite not being deeply familiar with her artwork, Mazzerello found inspiration in O’Keeffe’s iconic sense of fashion photographed by Alfred Stieglitz, to whom O’Keeffe was married from 1924 to his death in 1946.

In a male-dominated art world, female artists often find themselves reliant on endorsement from men for opportunities and visibility. Despite O’Keeffe’s undeniable talent, her ascent to stardom was amplified by Stieglitz’s support and promotion.

The 44.4 collective emerged as a space where women could take agency over their artistic narratives.

“It’s such a rich experience to work in a collective,” said Mazzarello “We give each other permission to try stuff and encourage each other to do so.”

In addition to her fashion-inspired creations, Mazzarello has curated a collection of photographs from her walks following the traumatic birth of her first child during the pandemic.

The digitally altered photos are meant to represent her self-transformation after experiencing a life-altering event and becoming a mother. Mazzarello said the original photos have taken on a “brighter and more optimistic” expression than when they were taken in times of struggle.

“Art making is about sharing what we know,” she said. “It’s about expanding our experiences out into the world.”

Mazzarello believes the support of her fellow collective members is essential to navigating and sharing these artistic experiences.

“There is so much more we can get done in community than we can on our own,” she said. “To think that I’m showing art at the Ottawa Art Gallery… that would have been an impossibility to tackle alone.”

Nobody Sees a Flower marks Moira Power’s curatorial debut at the OAG.

Although not a mother herself, Power said she was “instantly intrigued and inspired” when she learned about 44.4’s mission of questioning the ambiguity of motherhood. She attended critique nights at the artists’ studio to better understand the nature of the collective’s work and how it could best be displayed to reflect the artists’ unique lives.

“Once I heard that Alexa [Mazzarello] wanted to display clothing, I was instantly drawn to the idea of a clothesline,” she said. “I thought it connected with the theme of motherhood, as doing the laundry has traditionally been understood as a mother’s responsibility.”

Power said she felt encouraged by members of the collective to broaden her horizons for her first curatorial project.

“44.4’s positivity is contagious,” she said. “As a young woman beginning a new position in an unfamiliar space, they were extremely kind and understanding. It was almost as if their maternal nature had extended to myself.”

Speaking about their unique experiences as women, as mothers and as artists, mother-artists are challenging social perceptions and standards of motherhood.

“We’re here, we exist, we are mothers and we are artists,” said Mazzerello “We’re speaking together, and people are starting to listen – there is power in that.”

Nobody Sees a Flower runs until March 31 at the Ottawa Art Gallery.