The impending closure of a supervised drug consumption site in Somerset Ward has sparked concern among addiction experts and nearby businesses.

The Somerset West Community Health Centre’s supervised consumption and treatment service (CTS), two blocks from St Anthony School, will close next March. In August, the province ordered the closure of all supervised consumption sites within 200 metres of schools or daycares.

Eugene Oscapella disagrees with the closure. The lawyer and uOttawa criminology professor says that supervised consumption sites are part of “intelligent drug policy.” The first goal of these policies should be “to prevent death, the second should be to prevent disease, and the third should be to prevent dysfunction,” he says.

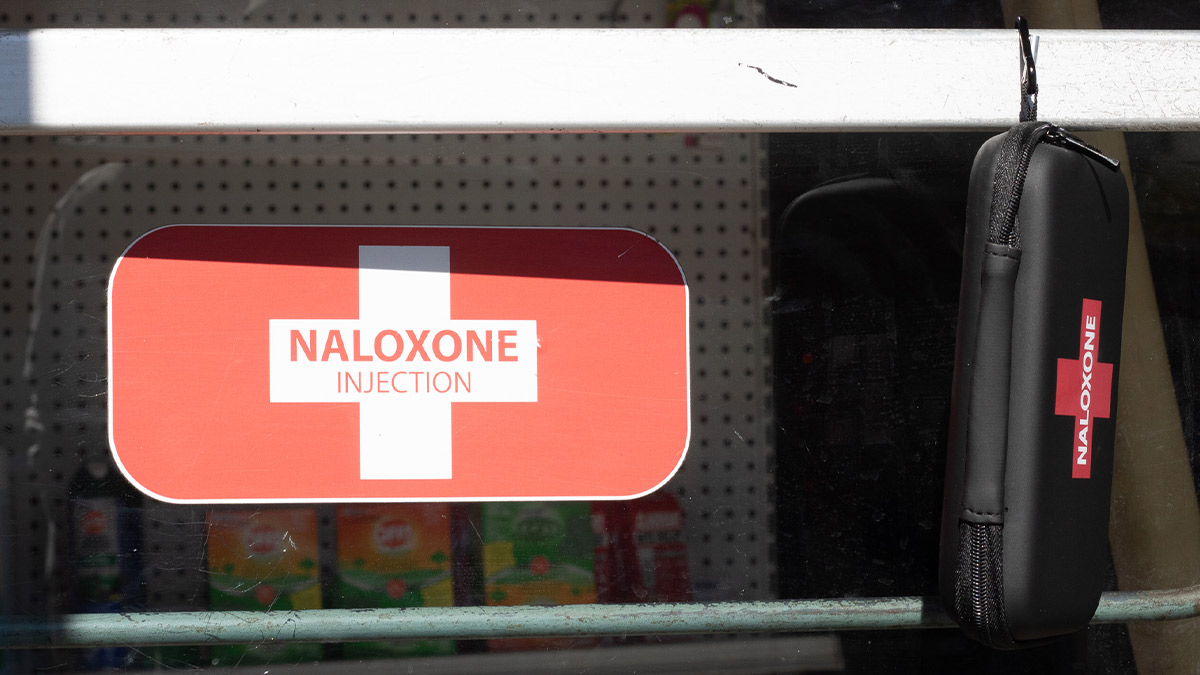

The first supervised consumption site in Canada, InSite, opened in Vancouver in 2003. These facilities, which require Health Canada exemptions from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, provide a controlled environment in which users can consume drugs with access to health care and overdose reversal medications. Somerset West’s CTS is one of three in Ottawa.

Staff at Somerset West CHC declined to comment on the closure.

The contamination of street drugs with fentanyl or other additives means the risk of fatal overdoses has risen, making supervised facilities — which can test street drugs for contaminates — even more important, says Oscapella, who is an expert on drug policy.

“You can’t help people if they’re dead.”

He says these sites are also points of contact for social services.

“Supervised injection sites aren’t just for using drugs. They’re also for helping to stabilize people and get them connected to the community so that they can maybe get mental health services, and maybe move away from problematic use.”

Business owners near the Somerset West CTS say encounters with people experiencing homelessness or addiction are common in the neighbourhood.

Emma Campbell co-owns Corner Peach café on Somerset Street. She says that staff often interact with CTS clientele.

Corner Peach staff are “all for” the CTS, Campbell says, despite thefts from and overdoses in the store.

“We think that that’s an awesome thing that should definitely stay,” Campbell says. “I just think there needs to be a bit more protection for the neighbourhood.”

Alexandra Chernuik of Giovanni’s Snack Bar & Pizzeria says the closure of the CTS is part of a larger issue within the community.

“These people are going to use anyways and now they’re going to use in an unsafe way,” Chernuik says. “We probably will have more overdoses and deaths as a result of it.”

Len Bunce, whose daughter attends St. Anthony, says there’s been more open drug use in the neighbourhood since news broke of the upcoming CTS closure.

“Where are they gonna go? They’re here, whether you like it or not,” Bunce says. “It’s a shame it’s beside a school and beside a place where a lot of families live who don’t have security [systems] … but what are you gonna do? Everyone deserves to be welcome and have a place in the community.”

It’s a lose-lose situation. A loss for the drug users who need health care and compassion and social services, and it’s a loss for the society around them.

Eugene Oscapella, lawyer and uOttawa professor

Bunce says she’s never seen drug use on the school grounds of St. Anthony, adding that the grounds are kept locked at all times and Somerset West staff conduct periodic checks in the area.

Gerald Potter is executive director of Ottawa Innercity Ministries, a charitable organization that supports people experiencing poverty and homelessness. He says that the level of need his outreach teams see on the streets is growing.

He calls the opioid crisis a “wicked problem” that’s only getting harder to solve, adding that it remains to be seen whether the change in provincial policy will have a positive outcome.

“These shifts are like steering a very large oil tanker: it takes a long time to turn, and we don’t know what the downstream effects will be.”

The province says that along with the closure of 10 of 17 supervised consumption facilities, it will invest $378 million in Homelessness and Addiction Recovery Treatment (HART) Hubs. It says these hubs will combine access to social services, addiction treatment and housing through a mix of “on-site and integrated care pathways.”

Oscapella questions this logic.

“You’re taking away a lifesaving measure, one of the few rays of hope that some problematic drugs users have, and you haven’t replaced it with anything yet,” he says. “If the government wants to prove its sincerity, let them set up the [treatment centre] beds and then shut down the supervised injection facilities.”

Closing the Somerset West CTS will likely mean more public drug use and public nuisance, he says. “If people don’t have a clean, safe place to use, they’re going to use in the street.”

“It’s a lose-lose situation. A loss for the drug users who need health care and compassion and social services, and it’s a loss for the society around them.”