Editor’s note: Since this story was first reported, CUPE 2204 says that an agreement has been ratified in October and that there is no possibility of a strike.

Christina Beauchamp, 59, has spent nearly 30 years working weekdays at Dalhousie Parents’ Day Care Centre, nurturing children and supporting families. But come the weekend, she swaps her day-care duties for house cleaning and scrubbing toilets — jobs that pay nearly double her day-care wage.

Beauchamp is among 95 workers at four Ottawa daycares fighting for a “living” wage. Represented by CUPE 2204, they’ve been locked in negotiations with the Ottawa Federation of Parents’ Day Care for 18 months. With contract talks at a standstill, a strike looms. (An agreement was reached in October and ratified.)

“We are caregivers. In our hearts, we don’t like controversy, we don’t want to strike, we don’t want to put our parents out,” Beauchamp told Capital Current. “But I deserve a decent wage, and I deserve to be able to live without working two other jobs. Why are we not valued, and why are we not valuing our children? Why is housekeeping valued more than child care?”

Some child-care workers earn a minimum of $23.86 per hour a rate that, the workers argue, falls short of what is needed to support themselves.

A strike could leave parents without reliable child care and forcing already financially stretched workers into an indefinite period without pay. Beauchamp emphasized the crucial role child-care workers play in the city, pointing to the COVID-19 pandemic as an example.

“The city couldn’t operate without us,” she said. “Paramedics, doctors, and nurses couldn’t go to work if you didn’t have child care. It’s a lose-lose situation all across the board. I can’t afford to strike, the centre will lose money, Parents are going to be scrambling for child care.”

Statistics Canada reports that from 2019 to 2023, living expenses in the city surged by nearly 17 per cent, placing further strain on already these low-wage workers who have not seen a raise for two years.

Abhann Cupper Scott, a child-care worker at Andrew Fleck Children’s Services and a spokesperson for CUPE 2204, told Capital Current the fight for a fair wage is also about securing the future of the profession by attracting and retaining qualified staff.

“At the end of the day, when we’re talking about increased wages and we’re talking about a fair deal that represents it goes hand in hand with good jobs. That’s how we keep staff in our field,” said Cupper Scott. “There’s a provincial crisis in our field, so it’s very much about retaining people and bringing in people.”

Beauchamp shared similar concerns about the future of her profession.

“Because of the pay, people aren’t going into the field,” she said. “I don’t encourage people anymore, because you struggle, and you might go get a second and third job to be able to survive.”

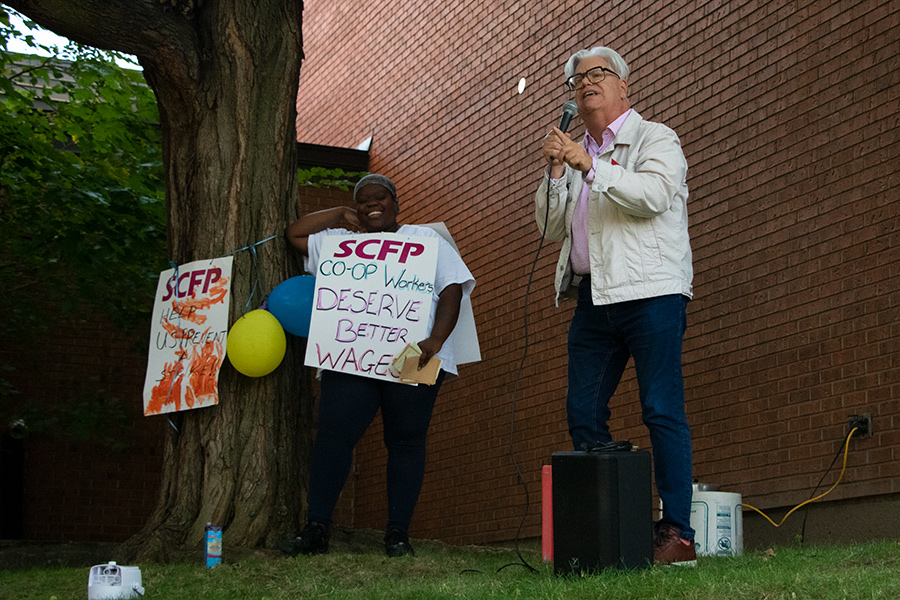

CUPE Ontario President Fred Hahn attended a recent rally for the child-care workers. He questioned why no provincial funding has been directed toward wage increases for these workers, despite Ontario being “the only province that forced the federal government to agree that fully one-third of that money could go to for-profit care.”

“We’re talking about child-care workers who are already undervalued in their pay. They are not paid enough for the work they do already,” said Hahn. “And now, we’ve got a centre that ought to understand the importance of workers, offering them a zero per cent wage increase. All of us have been through the last couple of years. We know the cost of living crisis that we’ve all been in.”

At the same rally, Ottawa Centre NDP MPP Joel Harden echoed Hahn’s criticism of the Ontario government.

“All of the deputy ministers of the Ford government got a 16 per cent raise last year. Do you think the staff here at this centre deserve a 16 per cent raise?” Harden told the rally. “CUPE 2204 members work wonders every single day. When our kids are hurting, or tired, or hungry, you’re there for them. I want a province that is there for you.”

The Ottawa Federation of Parents’ Day Care and Ontario’s Ministry of Education did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite the challenges she faces, Beauchamp remains deeply committed to her work. She loves her job but longs for the day she will not need to work two extra jobs to make ends meet. “It takes away from our ability to provide the best care that we can because we’re tired,” she said. “We need change. We need decent wages.”