Data showing that opioid-related deaths are falling in Ottawa is a hopeful sign various harm reduction measures may be making some difference.

The opioid epidemic has taken the lives of many Canadians, but experts say access to safe, clean spaces for users — and naloxone — are among the possible reasons for a change in trajectory.

“In the ER now, anybody that comes in with an opioid overdose, we give them a naloxone kit, we teach them how to use it and we send them home with it,” said Dr. Bhaskar Gopalan, an addiction physician and emergency physician at Queensway Carleton Hospital.

“That didn’t exist five years ago. There’s a lot of education on sort of how to use safely, how to avoid overdoses [and] how to use clean needles.”

Naloxone, also referred to as Narcan, is a fast-acting medication that is sprayed into the subject’s nose and temporarily reverses an opioid overdose. It can take effect within two minutes of being administered.

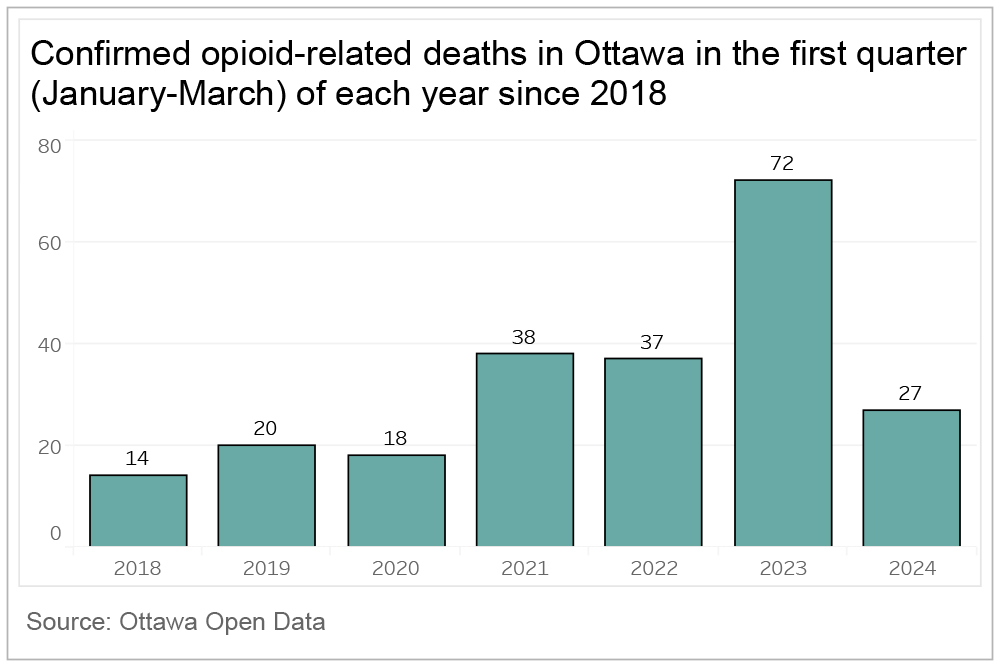

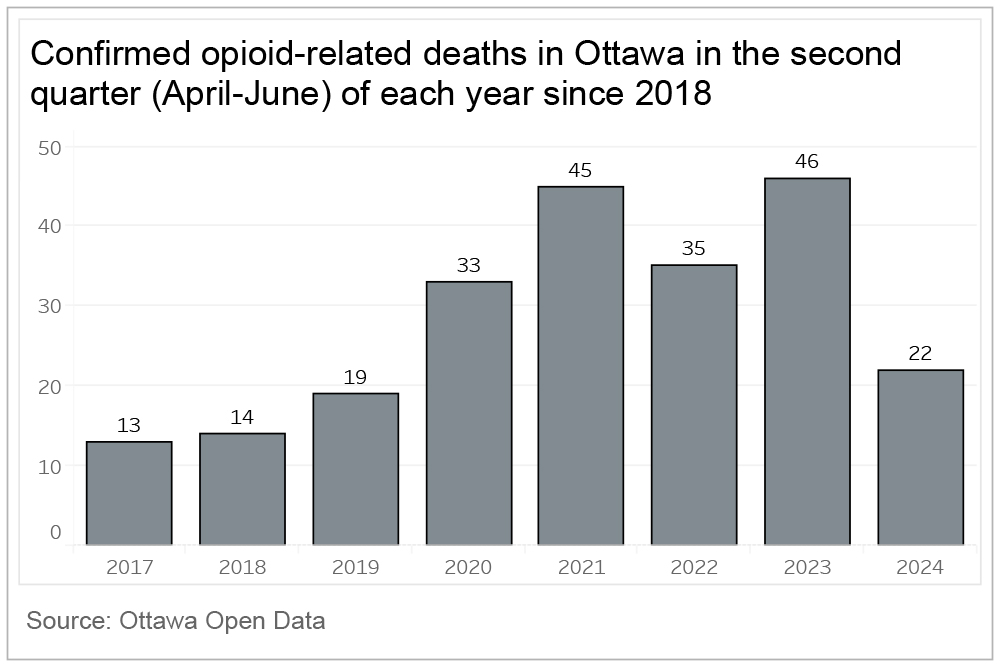

Data from Open Ottawa shows that between January and March 2024, confirmed opioid-related deaths were 27 – a sharp decrease from 72 deaths recorded during the same period in 2023 and 37 deaths in 2022.

“In the last three to four years, the opioid epidemic has been devastating to the community,” said Lise Laporte, a paramedic for 37 years in Ottawa and surrounding areas.

“The amount of users drastically increased during COVID. The amount of homelessness and hopelessness, through the charts,” said Laporte, who works in Brockville, Ont.

Statistics from the Public Health Agency of Canada showed 81 per cent of accidental opioid toxicity deaths in Canada involved fentanyl, a 42 per cent increase from 2016.

Of these deaths, 84 per cent were non-pharmaceutical.

“I’d say in 2021, 2022 I started noticing that they started putting fentanyl in heroin to get you addicted way faster. And you had a double effect, so the calls that we were responding to with those that were unconscious and barely breathing, spiked,” Laporte said.

In 2017, Ottawa opened its first Supervised Consumption Site (SCS), providing a safe space where people can bring their drugs to be tested for contaminants and use them under the supervision of trained medical staff.

These sites are now equipped with a Scatr’s device, which can detect if the street drugs people are carrying contain toxic contents, allowing them to make an informed decision on whether to use it.

Cassandra Piamonte, a harm-reduction worker at the King Edward Avenue and Murray Street location, said when most users are told their drugs contain other components, they’ll say no to using them.

“The risk outweighs the benefits in that case,” she said.

However, Piamonte said those who are battling with a stronger addiction may use the drug despite the increased risk of overdose but will ask the staff for support.

“So, it’s not like people are being tossed back onto the street with something unknown that could harm them, and they just have to deal with it. We will still monitor them,” she said.

Data collected from Canada’s Health Infobase on SCS, showed that there were 43,566 non-fatal opioid overdoses between March 2020 to May 2024, 17,713 overdoses requiring naloxone and zero fatal overdoses.

In August 2024, Ontario announced the planned closure of 10 sites across the province by March 2025, which has those in the medical industry worried this will result in a rise in fatal overdoses.

“We may see a rise of deaths again if people don’t have a safe place to use,” said Gopalan.

Gopalan has been specializing in addiction since 2015. He said that while the opioid epidemic has gotten worse, education and information are more readily available to the public compared to five years ago.

Naloxone only works for individuals using opioids, such as fentanyl, carfentanil, heroin, morphine or codeine. Since it binds to the same brain receptors as these drugs it reverses the effects of the opioids.

“The awareness and the knowledge of naloxone has allowed for the death rates related to opioids to be reduced,” said Laporte.

Despite fewer deaths, data from Open Ottawa shows emergency visits to hospitals related to opioid overdoses between 2023 and 2024, remains high.

Between February and September 2023, there were 927 emergency visits to hospitals in Ottawa related to opioid overdoses compared to 694 in 2024 during the same period.

Although naloxone prevents a fatal overdose from occurring, its effects only last for 30 to 120 minutes.

“There’s a lot more naloxone kits now,” said Gopalan. “People are very familiar with using it so [when] somebody’s overdosed, they’re able to use a naloxone kit [which] prevents death. But the problem is still there, so that’s why you still see emergency visits.”

Accessing a naloxone kit has become easier for those in need. It’s free and can be requested at any pharmacy.

Its accessibility, along with other safety kits has increased in Ottawa because of the Our HealthBox vending machine being located at the Carlington Community Centre since October 2023.

“We’re encouraging ways to reduce harm, that people stay safe, and show them that you care, that they have dignity,” said Sean Rourke, a clinical neuropsychologist at MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions at St Michael’s Hospital (Unity Health Toronto) who led the launch of Our HealthBox.

“We’re providing a low-barrier option for you to get what you need right now to stay healthy, to stay safe.”

OurHealthBox is a smart, interactive vending machine that dispenses free health supplies like self-testing HIV kits, COVID tests, women’s hygiene products, naloxone kits, sexual health items, safe injection kits, along with hats and mitts for winter.

Users must be over the age of 16 to register and the registration process is completely anonymous.

“There’s nothing in the Healthbox that can hurt someone. Naloxone can save someone’s life, these other things are just letting people know that they matter, that they’re important,” said Rourke.