Laura D’Angelo woke up to a troubling email from the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB) on Feb. 28. The mother of two saw a proposal, impacting thousands of K-12 students, outlining new boundary and grade configuration changes that would take effect as early as September 2026.

Under the plan, approximately 11,000 students would be required to switch schools to be placed in schools within “their communities,” according to the board — about 4,000 more students than the annual average. The plan would also see 30 K-12 schools restructured into a K-three and grade four-eight split, adding another transition for students.

“There’s no way that this plan is based on building up community, this is ripping communities apart. The boundaries that they’re proposing [don’t] cut along neighborhoods or community lines but directly in the center of them,” said D’Angelo.

She says her 4-year-old son currently attends Broadview Public School, in the city’s west end. Under the new boundary changes, when her youngest daughter begins Kindergarten next year, she will be attending Churchill Alternative School instead of joining her brother at Broadview. D’Angelo expressed concern that when her daughter turns 12 and enters Grade 7, she will no longer be able to attend the school just an eight-minute walk from home. Instead, she will be zoned to Fisher Park, requiring a 40-minute walk across multiple busy roads, which she worries will make for a much more dangerous commute. Most importantly, she worries about separating her children.

“A lot of parents, myself included, will have to divide and conquer. It’s devastating to have to make these decisions about how we’ll keep our family closeknit when there’s going to be these big differences forced upon us,” she said. “My son is only 4 and he’s so excited to be able to help his baby sister be introduced to the school and teachers already. Forcing them to go to different schools — the loss cannot be quantified.”

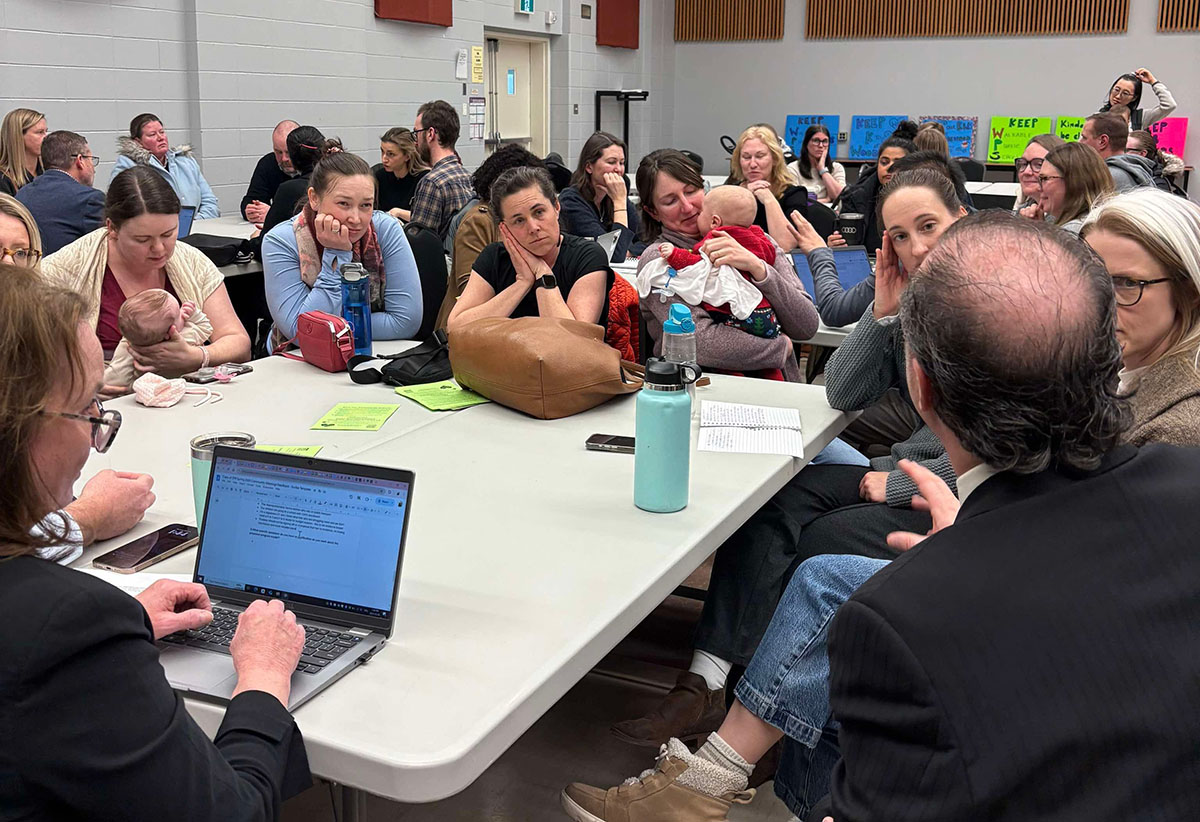

Since the announcement, hundreds of parents have reached out to the board, their district’s trustees and the media, raising concerns about what these changes could mean for their children. Siblings being split up, different pick-up and drop-off times, program changes in both English and French, lack of childcare and the loss of many special needs and alternative programming have been at the top of their lists.

Elizabeth Macdonald is also a mother of two. Her children, ages 4 and 7, both attend Woodroffe Avenue Public School. She recalls being consulted about potential changes earlier in the school year but is certain the most important aspects of the review were not shared with parents during the OCDSB Phase 1 Engagement.

“We were not told about the grade configuration changes or the changes to the school attendance boundaries until Friday. We now have less than a month to have our voices heard before trustees begin the voting process on Apr. 1.”

Over the weekend, Macdonald tirelessly reached out to her district’s elected representative Suzanne Nash, in hopes to get answers. When she finally heard back on Mar. 3, Nash detailed she would not “meet with parents until after the first round of motions and amendments.”

Angry and determined, Macdonald teamed up with parents from Woodroffe Avenue and began to push back. Within 24 hours, they had launched a website, distributed flyers to every mailbox in the affected zoning area and rallied those worried about the impact on property values now that a school would no longer be in their community. On Mar. 3, the concerned parents organized their first protest outside Woodroffe Avenue Public School, marking the beginning of what would be many more.

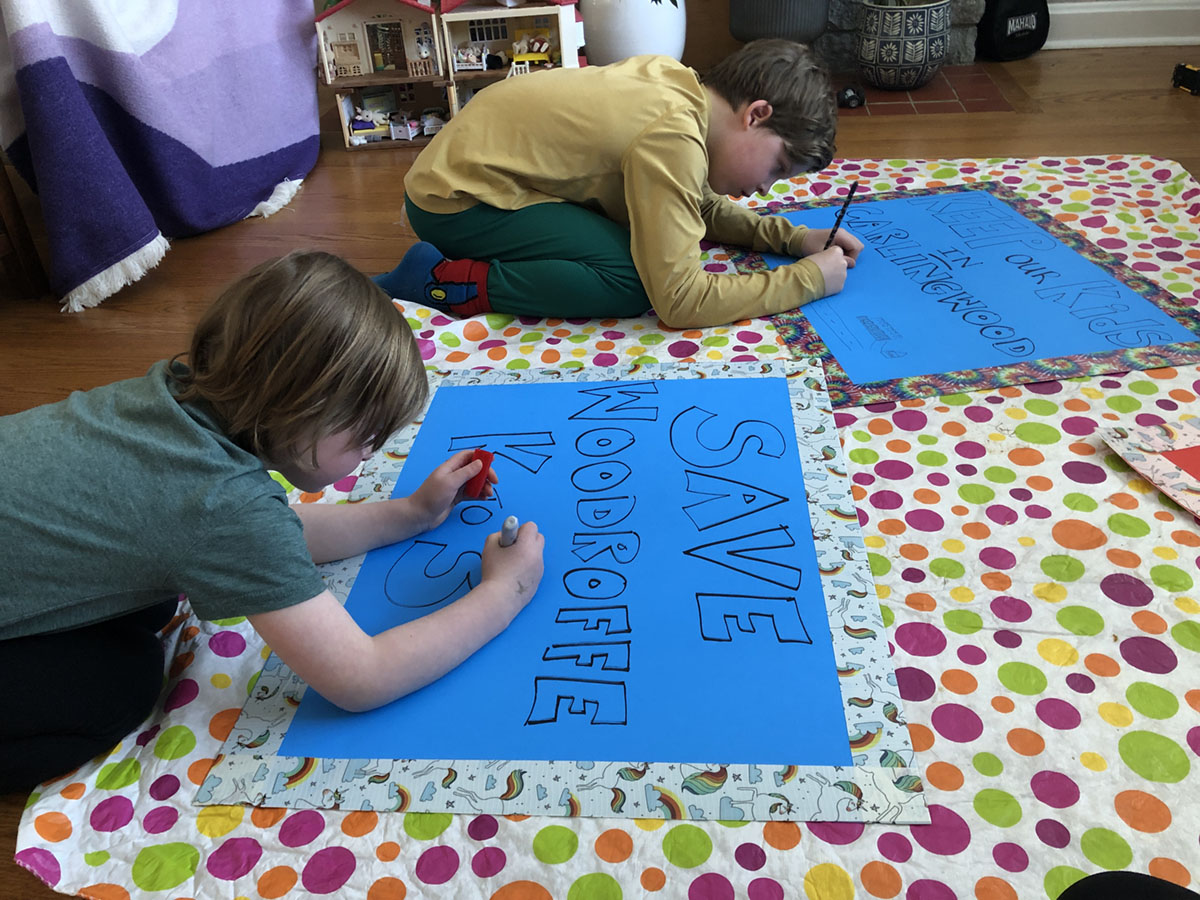

“My children and I stayed up late the night before making enormous signs. They are so deeply invested in this activism because they know full well that they’re being taken advantage of,” she said. “I feel this is an obvious failure of the OCDSB and the provincial government to secure adequate funding for education in Ontario and in Ottawa specifically. This is clearly a cost-cutting exercise disguised as a plan to build community, and our children shouldn’t bear the brunt.”

Similar concerns were voiced across the city. Shannon Worek, a concerned mother who chose not to disclose her children’s schools due to privacy concerns, launched a petition on Feb. 26 after realizing trustees were voting on this proposal “as a whole and not piecemeal.” Within a week, it had gathered 2,000 signatures from worried parents. At the time this article was written, the petition had reached over 2,600 signatures.

“There is no other reason that they would make difficult decisions like this, than budgetary ones and the lack of transparency is very problematic,” D’Angelo said in reaction to the petition and protests across other schools. “You would not see parents organizing this widespread, this quickly and frankly, this aggressively, if this plan made any sense and was working at all to build up community.”

Worek also recalls being consulted by the OCDSB but like Macdonald she says the changes were “broad[ly]” described.

“The tone of the proposal and the way that the consultation opportunities were framed, it wasn’t clear how significant the potential changes and considerations might be.”

According to the board’s timeline, Phase 2 Engagement will conclude with a vote. Parent surveys will close on Mar. 25, giving the board less than a week to review concerns before making a final decision on Apr. 1.

OCDSB Director of Education Pino Buffone acknowledged that “this is not a perfect plan” but emphasized that it is part of a four-phase process aimed at addressing issues of “equity of access and opportunity,” as many programs are currently only available at select schools.

“I really want people not to lose sight that we [already] move six to eight thousand students […], so what’s being described by the parents, and I really appreciate that every case is unique and different—is already happening in the district,” he said. “Students, siblings, already don’t go to the same school throughout their journeys.”

When asked how the board determined community boundaries, Buffone explained that they “de-coordinate boundaries in a way that allows students to transition as cohorts.” While he acknowledged the existence of various communities and recognized that “large-scale changes aren’t easy,” he confirmed that there is no Plan B.

Worek disagrees. “If [parents] are forced to change schools, they will not just be automatically accepting whatever school the OCDSB has dictated for them — they will be looking at all the options that are available to them.”

For Macdonald, whose daughter will be assigned to Regina Street Alternative School — 3 km from home and past other closer OCDSB schools — the Ottawa Catholic School Board (OCSB) is emerging as a possible alternative to avoid the “logistical nightmare” of having her children attend separate schools. However, the OCSB does not align with her family’s values or religious beliefs, leaving her, like many others, at a crossroads.

“I have a genuine fear that I will lose my job,” she said. “I don’t know how I will get two children who can’t walk independently to school at two different drop off times.”

This concern was echoed by three other moms who spoke to Capital Current on the boundary changes, including D’Angelo.

“It’s very clear that this plan was built without any regard for gender-based equity,” she said. “Whenever we see changes in policies that are implemented like this one, they vastly affect women over men. We’re going to see women having to leave the workforce to care for children and deal with those issues.”

With the Apr. 1 deadline approaching, more parents are mobilizing in an effort to intervene before it’s too late. If the proposal is approved, the OCDSB has indicated that programs and schools will be subject to further review in the coming years.

“No family should feel completely safe from these potential disruptions, and pushing this forward could set a dangerous precedent,” Worek said. “Even if a family isn’t directly impacted by these upcoming changes, the uncertainty will still linger for anyone with a child in an OCDSB school.”

For now, the proposal remains under discussion, though Buffone has made it clear there is no alternative plan. Worek is urging parents to contact their trustees, sign the petition, and find ways to advocate for their children and the educational choices being made on their behalf.

“A lot of parents make significant life decisions around what school their child will go to, this proposal completely undermines all the careful planning that parents have made around their child’s education and future,” she said. “Advocate for your child and the education decisions you’ve made for your child.”