This spring, as the City of Ottawa reviews its options for the future management of municipal waste, officials will explore a controversial proposal to build a waste-to-energy incinerator.

Local environmental groups are concerned about the emissions and toxins that could be produced by an incinerator and argue the facility would incentivize overconsumption instead of encouraging greater waste reduction and higher rates of diverting recyclable material from landfill.

The past June, the city approved its Solid Waste Master Plan and among the recommendations in was one to consider waste recovery technology, including a municipal incinerator. The plan said, however, that the implementation of a recovery technology project would take a decade before it becomes operational.

An incinerator would would reduce the volume of undiverted waste by 73 per cent, according to estimates in the city’s plan. The remaining material, mostly in the form of ash, would be put in a landfill.

Waste-to-energy is not considered a diversion technology by the Ontario government, but some councillors see benefits in it as a long-term waste solution.

Rideau-Jock Coun. David Brown said he feels now is the time to start doing something. He wants to see the incinerator online before the Trail Road landfill — the city’s main dump, about seven kilometres west of Manotick — runs out of space.

Capital Coun. Shawn Menard, chair of the city’s environment and climate change committee, said council needs more information. In a March 29 email to Capital Current, Menard confirmed that no feasibility study has begun.

Yet Brown, whose ward contains the Trail Road landfill, said he’s heard enough to know that he and his constituents would prefer a waste-to-energy incinerator.

Brown says the landfill is in its end-of-life phase, but can be prolonged by expansion of the present site or by having a portion of the city’s waste shipped to other facilities.

Environmentalists have long argued that the best way to extend the life of the Trail Road dump is to improve rates of diverting recyclables and reducing the generation of waste.

Council has requested an environmental assessment to expand the landfill by 5.5 million cubic metres, pushing the projected retirement of the facility from 2034 to 2048.

“As we look at what we’re going to do long-term, waste-to-energy … seems to be a common-sense opportunity to solve our waste problems, which is why that’s my preference,” said Brown. “I believe it’s also the preference of the majority of council and taxpayers who ultimately have to pay for (it).”

Brown points to examples of incinerators in “progressive” countries that have been using them for decades, even near city centres. He calls it a “made in Canada” solution that would create local jobs without needing to ship garbage south.

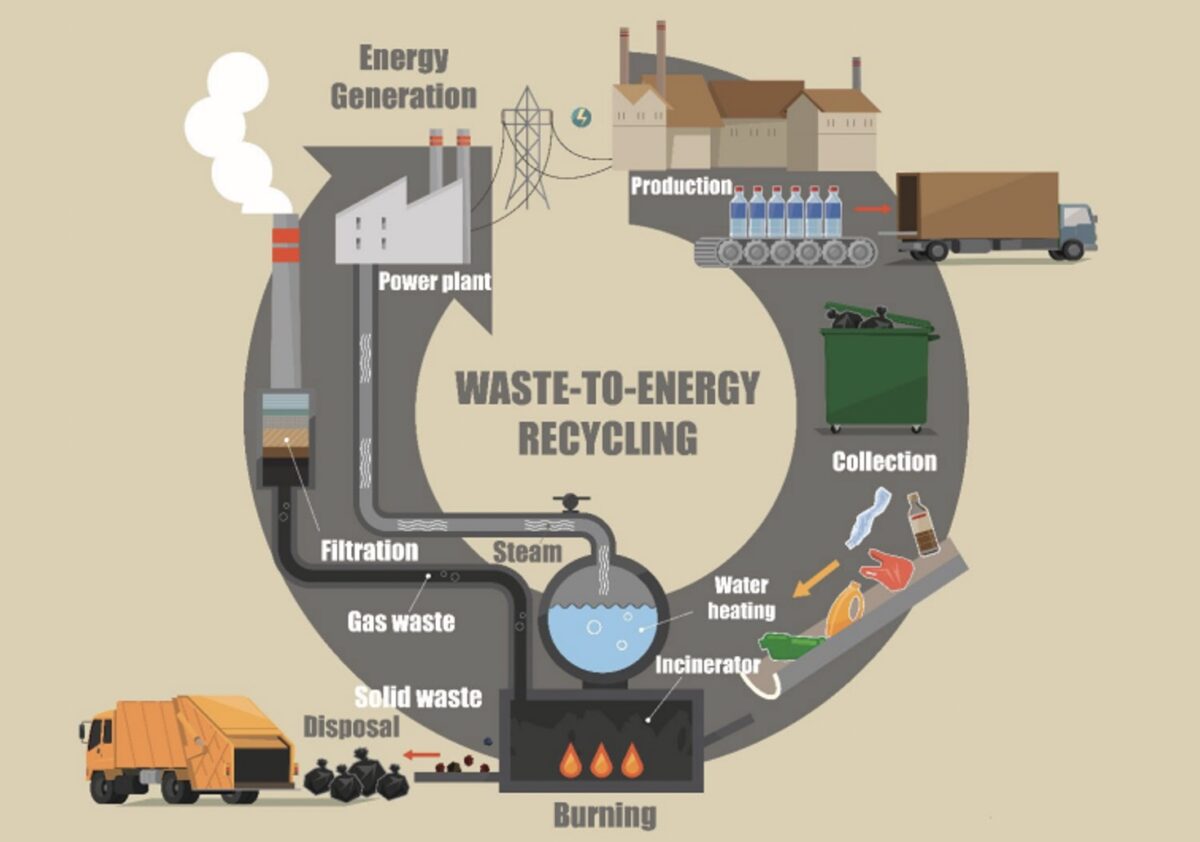

He said an incinerator would have additional benefits, such as district water heating, energy through electricity and renewable gas in the form of methane that can be injected into natural gas lines for community heating.

The city’s master plan also indicates incineration presents some revenue generation opportunities but is not expected to fully offset its operational costs.

“There are several opportunities, but the big one is we stop burying garbage because that is the worst environmental practice that you can take,” said Brown. “I’ve made it clear that if council doesn’t want to make a move towards a more progressive solution, then another ward can take the next landfill.”

“Ottawa is definitely not a leader in waste management in Ontario. There are other cities that divert far more of their waste,” Angela Keller-Herzog, the executive director of Community Action for Environmental Sustainability (CAFES), said. “I think there’s a general number around that about 50 per cent of the stuff that ends up in the Trail Road landfill could be diverted.”

This is confirmed by numbers in the city’s plan, which notes that “residents are putting 25 per cent of blue bin and 21 per cent of black bin recyclables in the garbage.”

Only half of residential homes and one-third of multi-residential properties use green bins. The prevalence of organic materials ending up at Trail Road produces methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times stronger in heating the atmosphere than carbon dioxide.

“Waste-to-energy, at very first glance, sounds like a fine idea, but at second glance, it’s not a good idea at all,” said Keller-Herzog, citing the emissions — including possible carcinogens — coming from incineration. “It’s not that there is a more modern technology that then makes incineration … harmless in terms of its public health risks.”

CAFES recently held a community information session about incineration, hosting experts such as U.S. environmentalist Mike Ewall, founder and director of Pennsylvania-based Energy Justice Network.

Ewall said he believes incineration as a form of energy production “dirtier” than coal in terms of air emissions. It’s a comparison based on several in-depth research projects done by his organization.