Nukes. Bombs. War. North Korea. These are words Jenny Kwak, a 22-year-old Korean-Canadian, often heard when people discussed her heritage.

Growing up in Toronto, she always felt like she stood out. Her food was different. Her features didn’t fit in. When she met people who weren’t from her community, she learned to steel herself for the stereotyping.

Then came 2012, when the music video “Gangnam Style” by South Korean artist PSY exploded onto the global stage, racking up more than 5.4 billion views worldwide. For the first time, Kwak’s family saw a Korean artist perform in front of millions in New York’s Times Square.

It was a glimpse of something new — a Korea beyond headlines about bombs.

Eight years later, K-pop bands such as BTS, BlackPink and Twice are famous worldwide, and the Korean film “Parasite” won a Oscar for Best Picture. Everything had changed. Kwak no longer had to explain her culture. People were finally seeing Korea in a new light, free from the old stereotypes.

In 2022, U.S. listeners streamed K-pop 6.6 billion times; in 2023, that figure rose to 9.2 billion, making the U.S. the world’s second-largest K-pop streaming market after Japan.

And in 2023, Netflix committed $2.5 billion U.S. over four years to Korean content. K-dramas have gained attention worldwide, with hits like “Squid Game” attracting hundreds of millions of viewers around the world.

The global rise of K-pop and K-drama, known as the Hallyu or the Korean Wave, has reshaped how people perceive Korea.

And yeah, being Korean is great. I love saying that I’m Korean.

Jenny Kwak, uOttawa student

It also raises important questions about how deeply this trend can change societal attitudes.

For the Korean diaspora, global success marks a significant shift in how they are perceived, offering a sense of pride and belonging, in Canada and abroad.

Han Lee, the PR manager for the Korean Cultural Centre Canada (KCCC), said K-pop exploded in popularity during the pandemic, as people searched for new ways to stay entertained during lockdowns.

“Somehow, it just blew up like crazy,” he said.

The KCCC, established in 2016, promotes Korean culture in Canada through public events and education.

Korea was previously known primarily for its war history and political tensions, Lee recalled.

“They don’t know what ‘the actual people are like,’” or what the cultural trends are in Korea, such as music, Lee said. This information “was available, but nobody really cared or even knew about it.”

Today, many Canadians without any ancestral ties to Korea actively participate in the centre’s events, from online Korean cooking classes to in-person K-pop cover dance contests. Korean-Canadian families also regularly bring their children to learn more about their heritage, he said.

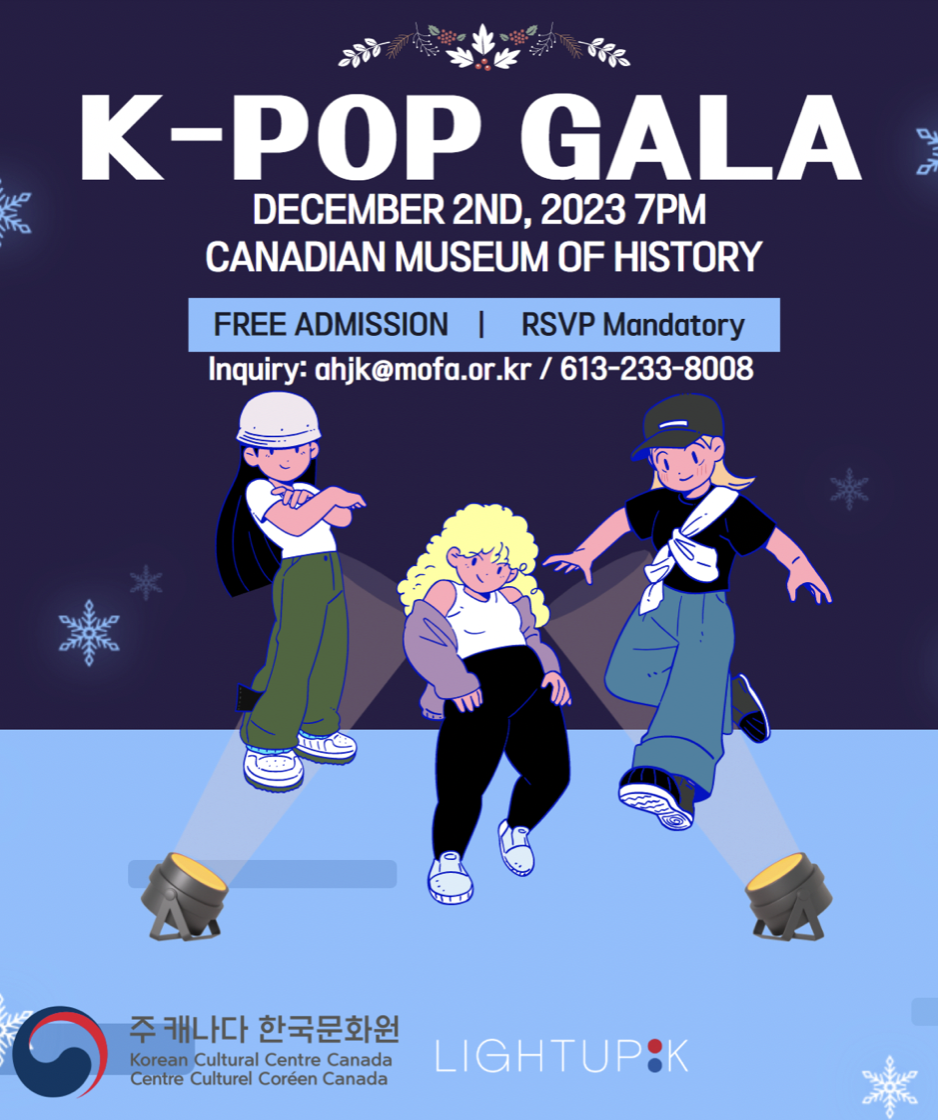

Lee highlighted a 2023 KCCC event featuring an in-person K-pop gala, with dance performances from teams across Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto, which drew thousands of enthusiastic attendees. “It was amazing,” he said.

According to Ji-yoon An, an assistant professor in modern Korean popular culture at the University of British Columbia, exposure to Korean culture is reshaping how Asians are represented in Western media.

The rise of Korean culture

The rise of Korean culture challenges stereotypes and broadens perceptions of Asian identity, she explained. “Any kind of visibility and exposure that Korean culture can bring, I think it’s always going to help tackle stereotypes,” she added.

An pointed to Mr. Sunshine, a historical Korean drama and the first Netflix original produced in South Korea, as a prime example. The series, deeply rooted in Korean history and rich with traditional costumes and cultural references, offers a version of Korea many Western audiences wouldn’t otherwise know.

She noted that viewers are often inspired to learn more about Korea’s past after watching the show,— highlighting how such content promotes cultural authenticity while still resonating with global audiences.

That said, she cautions, “I think it’s true that Asian visibility is still weak globally. And we still are in a white hegemonic kind of representation and culture, at least in Canada and North America.”

Hyounjeong Yoo said she has seen the impact of the Korean Wave firsthand. A Korean immigrant, Yoo introduced the first university-level Korean language courses at Carleton University in 2016.

Once dominated by Chinese female students, Yoo’s classes now reflect a diverse mix of students from various backgrounds, including India, the Middle East and across Canada.

“There is so (much) diversity, I feel that.” Yoo said.

Korean is now the third most popular language in Carleton’s linguistics department, after Spanish and Japanese. While many students are initially drawn through K-pop and K-drama, they often develop an interest in Korean history and culture, Yoo said.

“If you don’t have any cultural interest, it’s really hard to keep learning,” Yoo said. “Those interests make student keep working, learning (the) language more.”

In a 2021 article in The Conversation, on the impact of the Korean Wave, Yoo discussed how the Western film industry has historically confined Asian actors to stereotypical roles. K-pop’s influence is helping to challenge those limitations, opening more doors for Asian artists, she wrote. For example, Korean-American actor Ma Dong-seok (also known as Don Lee) was cast as a superhero in Marvel’s Eternals, and Blackpink’s Jennie made her acting debut in HBO’s The Idol — both major platforms that signal shifting attitudes toward Asian representation in Western entertainment.

“Korean culture really stands out now,” she added in an interview. “They see the Koreans are cool; it means that maybe they can see Asian culture (is) also cool.”

The Korean Wave

Beyond influencing pop culture, the Korean Wave is also helping Korean-Canadians reconnect with their heritage.

Young Korean-Canadians often go through different phases of ethnic identification, according to the 2022 book, Diasporic Hallyu. Some distance themselves from their Korean roots as children, only to embrace them later in life, the book said.

Lee said K-pop often acts as the first step. “So K-pop, you (get) into it, it’s a hook, and you delve deeper into the actual traditions, or what the actual language is like,” he said.

Korean culture really stands out now. They see the Koreans are cool; it means that maybe they can see Asian culture (is) also cool.

Hyounjeong Yoo, Carleton University professor

He said he has noticed an increase in second-generation Korean-Canadians bringing their children to the centre to learn more about their heritage.

“Having these cultures blowing up really is giving them a sort of a direction as to where to go,” Lee said.

Parents, once hesitant, now encourage their children to learn Korean and embrace their heritage, he said.

An said the rise of Korean culture has had a greater impact on the diaspora than on Western perceptions of Korea. “These diasporas often have had no visibility of people like them,” An said. “But to see that kind of engagement, we see more bridges being built.”

But there are some downsides to the Korean Wave.

Downsides

Kennes Lin, the former co-chair of the Chinese Canadian National Council Toronto Chapter (CCNCTO), said Asian representation in Western media remains largely controlled by those outside the Asian community, creating a gap between how Asians are portrayed in the media and their real-life experiences.

However, she sees the potential for change, particularly with the growth of digital platforms, which allow Korean musicians and content creators to reach global audiences directly. “That could be an amazing opportunity for celebrities to use that platform.”

In fact, some Korean idols are leveraging their fame to promote positive change. In 2022, K-pop group BTS attended a White House press briefing and met with then-president Joe Biden to discuss Asian representation, inclusion and the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes.

Lin said it was a significant moment.

“It’s great that advocacy groups put in years of work to prepare the key messages, so when celebrities speak on these issues, they are advancing a cause that has long been fought for.”

Another concern about the Korean Wave is that the “K” in K-pop and K-dramas is being diluted to appeal to a worldwide audience. Each year, new K-pop groups debut, yet some contain no Korean members, such as Blackswan, a girl group that identifies as a K-pop group and sings in Korean.

The current lineup of Blackswan includes members from India, Brazil, Senegal, and the United States. Although the group is signed to a Korean agency, trained under Korea’s idol system, and performs in Korean, some observers question whether K-pop can still be called “K-pop” without Korean representation.

Many people worry this trend could contribute to a cultural drift or skills drain, while others, like Lee and Yoo, argue that such groups reflect the natural evolution of a genre that now has fans and performers around the world.

The worldwide reach of Hallyu is also raising concerns that western K-pop fandoms are increasingly dominated by “Koreaboos” —non-Koreans who are overly obsessed with Korean culture. One high-profile example is British influencer Oli London, who made headlines after undergoing multiple cosmetic procedures to look like BTS member Jimin and controversially claimed to identify as Korean. This statement drew significant backlash for appropriating Korean identity rather than acknowledging or respecting its cultural roots.

As this trend grows, so do concerns about cultural appropriation and the line between admiration and fetishization.

Despite these concerns, Lee and Yoo argue that the essence of K-pop remains intact. They believe that while K-pop is evolving, its core — its rigorous training system and structured format — will always stay true to its Korean roots.

But even as Korean culture has found new fans around the world, that visibility has not protected Asian communities from rising hate.

Anti-Asian racism

In Canada, anti-Asian racism and harmful stereotypes became more common during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Statistics Canada, police-reported hate crimes against the Asian community rose by a staggering 143 per cent from 2019 to 2022, with an 18 per cent increase from 2021 to 2022. The surge was primarily fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which was first identified in Wuhan, China, in late 2019.

Although the origin of the virus remains debated, early reports linked it to a seafood market in China that sold live animals, which triggered a rise in racist backlash against East and Southeast Asian communities.

Lin said anti-Asian hate worsened during the pandemic.

During that time, people of Asian descent saw a sudden “increase in overt racism,” Lin said, including “very blatant interpersonal types of racism, including physical assault and attacks.”

Although data from Statistic Canada’s 2023 suggests a decline in police-reported hate crimes targeting East or Southeast Asians — from 312 cases in 2021 to 192 cases in 2023 — the number remains nearly triple the pre-pandemic levels, which stood at just 67 cases. Lin says many incidents are not reported, meaning the actual number is likely much higher.

Youth are particularly vulnerable. A 2022 national report by the CCNCTO found that racist incidents targeting children and adolescents (18 and under) rose by 286 per cent from 2020 to 2022, while cases involving young adults (ages 19 to 35) increased by 43 per cent. In 75 per cent of cases, perpetrators were identified as white men.

“We know that the profound sense of not being able to do anything about their situation would have a long-lasting impact on their self-determination, or even feeling like they have a sense of being an equal citizen in Canada,” Lin said.

A 2023 study published by researchers at the University of Toronto and the Hong Fook Mental Health Association, an organization that supports Asian communities in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), found that many Asian youth described racism as a daily, normalized experience–what the researchers referred to as “casual racism.” This included jokes about their food and facial features, exclusion in social settings, and being stereotyped.

According to the researchers, these experiences can profoundly shape identity formation. Participants also reported feeling invisible in everyday life, yet hyper-visible when portrayed as a threat or potential source of disease.

Hannah Xu, head of youth and family services at the Hong Fook, said that youth who come to the centre for help described being bullied at school, verbally harassed on the street, and experiencing hate in online spaces.

Exposure to racism can lead to mental health problems, primarily depression and anxiety, she said. For example, students with anxiety may have panic attacks or social anxiety; such issues can then “increase their risk to stay at home and not (go) to school.”

Despite these problems, the spotlight on anti-Asian racism has faded in recent years, Lin said. At the height of the pandemic, there was “a lot of consultation at all levels of government,” but those conversations have “quieted down” since then, she explained.

For many Korean-Canadians, the rise of Hallyu has helped to foster a sense of pride in their culture and a desire to deepen their connection with it, despite the surge in anti-Asian racism.

Jenny Kwak is one of them: after completing her first year at the University of Ottawa, she travelled to South Korea for four months to reconnect with her roots.

During that time, she discovered a new depth to her Korean identity, she said. And she realized there was a lack of Korean cultural celebrations in Ottawa. This realization inspired her to take action.

Upon returning, she connected with other Korean students at her university and founded the University of Ottawa Korean Student Association (UOKSA). The club’s mission is to celebrate Korean culture and introduce others to it.

“It’s like, nothing scary,” Kwak said. “It’s just a little bit different than Western culture.”

Nowadays, Kwak said, more and more people tell her that they think being Korean is cool and express interest and appreciation for Korean culture. This makes her feel accepted in Canadian society, she said.

This acceptance has made her feel proud of her heritage and motivated her to share Korean culture with others — especially Korean Canadians who lack strong connections to their roots.

“And yeah, being Korean is great,” Kwak said with a smile. “I love saying that I’m Korean.”

This story was originally published in Ricepaper Magazine. © 2025 Ricepaper Magazine.