Though Ottawa doctor Susan Wilkinson has been practicing medicine for 44 years, she can’t seem to retire just yet. When she closed her practice of more than 3,000 patients in 2022, she decided to continue virtual care, despite being “well past the age that she should be doing it.”

Her hesitation comes in part because it is harder to access professionals for health information and easier to get misinformation.

“Everybody’s on social media, everybody’s on all these platforms, and it gets disseminated so quickly,” she said. “It’s very hard to actually, to stand up and say, ‘there’s no value to this, this is absolutely misinformation,’ and I don’t ever recall a time when we had to deal with something like that.”

One result has been distrust in vaccinations, she says, particularly on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic. With vaccine rates slipping in Canada and around the world, Wilkinson is reminded of the early days of her medical career when there were far fewer immunization options.

When Wilkinson was a medical resident, the modern dose of measles, mumps, and rubella was not yet standard across the country. She recalls the fear of seeing a child with encephalitis, a serious complication of measles associated with a high mortality rate and long-lasting neurological symptoms.

“If we go back to these days when nobody believes in vaccines, we are in terrible trouble, and that’s very dangerous,” said Wilkinson. “People are going to die because there is no treatment. You either get better or you don’t.”

Dr. Trevor Arnason, the medical officer of health for Ottawa Public Health (OPH), is also concerned about misinformation and disinformation around the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. He notes a decline in vaccinations has led to outbreaks.

“Diseases that have been eliminated by vaccines are returning,” he said.

Factoring in the spread of incorrect information about vaccines has been a theme in recent OPH immunization campaigns, including in an RSV immunization campaign which started earlier this month. The team monitors information on social media and meets with community members in neighbourhood health and wellness clubs to better understand attitudes.

“We certainly recognize that minsinformation about vaccines is a major problem,” Arnason said. While he notes it’s normal to have questions about vaccines, social media algorithms often favour content that elicits emotional or angry reactions, not necessarily truthful information.

Declines in vaccine uptake means increases in hospitalizations and deaths, he says.

Misinformation on the rise

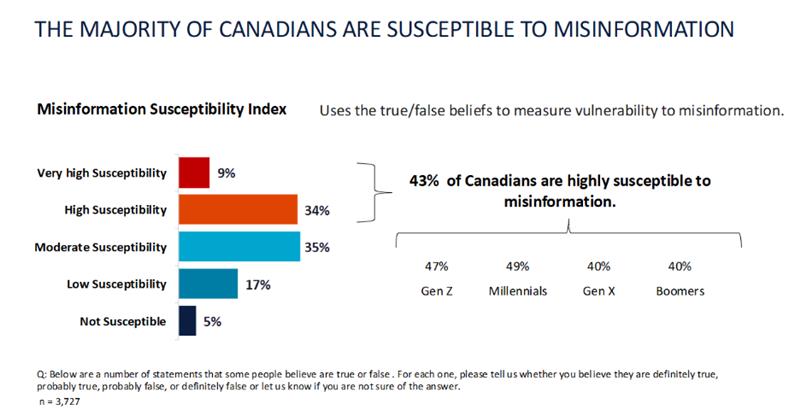

Earlier this year, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) published findings from a joint survey with Abacus Data on health and the media. The report suggested encounters with health misinformation are rising and respondents are increasingly recognizing the prevalence and harm of misinformation.

Some types of misinformation identified include negative beliefs about vaccinations or beliefs that cancer can be caused by 5G technology or prevented by lifestyle choices alone.

Some 37 per cent of respondents reported having to “use medical advice [they] found online because [they] couldn’t access a doctor or medical professional for help.” Twenty-three per cent also reported a negative impact or adverse reaction to acting on health advice found online.

Graphic by the Canadian Medical Association from a 2025 joint survey with Abacus Data.

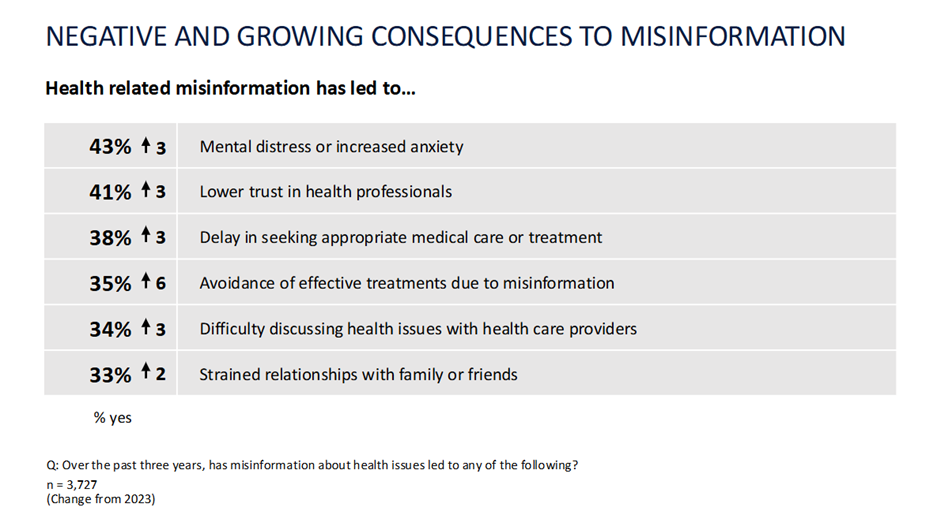

“The repercussions of misinformation are even more concerning,” wrote the CMA in a Jan. 21, 2025 press release. “The survey points to a direct link between misinformation and negative health outcomes — and it’s a growing problem.”

The same survey also found a decline in trust in health news and scientific studies.

Carleton University health communication and misinformation researcher Joshua Greenberg says the effects of misinformation go beyond personal health impacts.

“Misinformation can increase cost of health care,” he said. “It can expose people to infection, it can lead to preventable infection, preventable deaths, hospitalizations, when people avoid seeking access to health care because of misinformation, it can cause people to delay getting surgeries. It can exacerbate inequities and inequalities.”

Health communication and misinformation researcher Joshua Greenberg says misinformation has widespread effects on society. [Photo © Mia Parker]

Through all these impacts, misinformation can undermine trust and social cohesion, Greenberg says. Though gossip and rumours around medicine have always existed, he says social media can accelerate the spread of false information.

“We now have access to more information from more sources than we’ve ever had access to before,” he says. “The efficacy of those sources, our ability to verify whether they’re trustworthy or not, is much more challenging today than it’s ever been in the past.”

Respondents to the CMA survey were also asked about non-health-related misinformation commonly shared on social media, as well as health misinformation. Findings show 69 per cent agree that “climate change is primarily caused by human activities, namely the burning of fossil fuels,” (11 per cent said they weren’t sure) and 63 per cent agree that “humans evolved from earlier species of primates” (14 per cent weren’t sure). However, only 48 per cent of the respondents agreed that “masks [could] stop the spread of airborne illnesses,” and 41 per cent believed that an actual health professional (such as a doctor) will provide better diagnostic and treatment options than AI.

Graphic by the Canadian Medical Association from a 2025 joint survey with Abacus Data.

Why might people be more susceptible to medical misinformation? Greenberg suggests simply that it is “more personal.”

Misinformation can come from chatter and speculations between friends, or, “arguably the most powerful office in the world,” he says. In a Sept. 22 announcement, U.S. President Donald Trump indicated that the use of acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, during pregnancy is responsible for the “autism epidemic.”

Health Canada says there is “no conclusive evidence that using acetaminophen as directed during pregnancy causes autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders.”

CMA President Margot Burnell agrees that Tylenol does not cause autism.

“False information doesn’t recognize borders, and so I think we have to be on guard for that,” she said. “We see it when patients come and present some of these ideas to us in our offices, that we have to take the time to start having those discussions, and it’s building trusting relationships to have those difficult discussions.”

She emphasizes the importance of improving health literacy, the understanding of medical terms, data and clinical trials. She also wants to see health information providers meeting Canadians where they are including on social media.

Better access to trusted providers needed

Ultimately, trusted medical professionals are a large part of the fight against misinformation.

“We need to increase our access to primary health care,” said Burnell. “The reason for that is people are going to social media when they can’t get into their health-care provider, or when they haven’t built a trusting, lasting relationship with them.”

Burnell is calling on the Canadian government to focus on primary health care and set standards and safeguards to support the training of new physicians and the implementation of health-care teams, which would allow a distribution of care responsibilities.

She is also advocating for pan-Canadian licensure, meaning a registered physician in good standing with one province could seamlessly practice in another province.

“I think we just need to be putting out the good science and reassuring people, and then hopefully they’re going to make good decisions,” says Wilkinson.