The city’s move to scale back its commitment to affordable housing at Lansdowne 2.0 has left opinion divided on the extent of the impact on the escalating affordable housing crisis.

The latest Lansdowne revitalization proposal, released Oct. 6, promised even less of a commitment than the original proposal, earmarking just $3.9 million for affordable housing.

The amount “is a drop in the bucket,” says Carolyn Mackenzie, chair of the Glebe Community Association planning committee.

In 2021, when the city and the Ottawa Sports and Entertainment Group (OSEG) were negotiating the revitalization of Lansdowne, among the city’s key priorities was that affordable housing would be a consideration in whatever was negotiated.

However, one of the most significant changes in the latest proposal is the removal of the third residential tower, cutting the number of available units from 1,200 to 770. The city also pulled away from their original requirement for 10 per cent of the units to be sold at affordable rates.

“I’m willing to vote against Lansdowne as it does not create enough deeply affordable housing, onsite or elsewhere.”

– Kitchissippi Ward Coun. Jeff Leiper

Dean Tester, co-founder of Make Housing Affordable, has concerns over the supply-side effects of removing the third tower. “Losing 500 homes on this site could serve as a major supply shock to a market as I understand it is quite heavy in demand and short on supply,” he says.

Kitchissippi Coun. Jeff Leiper, chair of the planning and housing committee, is less convinced that losing the tower will have a major impact on housing affordability citywide, arguing that while the 550 units are a loss, the affordability of those units was always in question.

“The private sector’s role in affordable housing will be limited,” Leiper says. “If we are truly going to have affordable housing, it’s going to be up to the state to build it, or with help from our not-for-profit partners.”

For Leiper, the bigger concern is the level of contribution that the project makes to affordable housing overall.

“The $3.9 million directed towards affordable housing is simply not enough to make much of a difference,” Leiper adds.

Leiper takes issue with the city waiving its policy requiring 25 per cent of the revenue generated from the sale of public land for private residential use to go to the city’s affordable housing budget.

“Why do we have these policies if we are largely just going to ignore them?” asks Mackenzie.

From the city’s perspective, the reduction in population density because of the removal of the third tower meant there was lost revenue from property taxes, impacting the financial viability of the project, according to a revised plan released Oct. 6.

The city would pay about 20 per cent more for onsite affordable housing. Given the construction schedule of seven to 10 years, the city could get the best “bang” for its buck if it were to take the revenue generated from the sale of subterranean and property air rights and put it directly towards ongoing affordable housing projects off-site to help meet an urgent need.

Carolyn Whitzman, a housing expert at University of Ottawa, says the impact of $3.9 million from the project on the housing affordability crisis in Ottawa will be “extremely minimal.”

“This project doesn’t help anyone other than the rich developers.”

– Carolyn Whitzman, University of Ottawa housing researcher

“If the city was serious about tackling the housing affordability crisis, there needed to be much more of a public benefit,” Whitzman adds.

Based on the report, the city seems to have prioritized public-realm enhancements, such as more open spaces and community areas, at the expense of maintaining its original commitment to affordable housing. The city attributes this prioritization to “concerns expressed by the community in the consultations on the public realm,” according to the report.

However, as Mackenzie notes, the city does not mention its own Urban Design Review Panel in the latest report, which expressed similar concerns over the added density of the third tower and how it reduces public-realm areas.

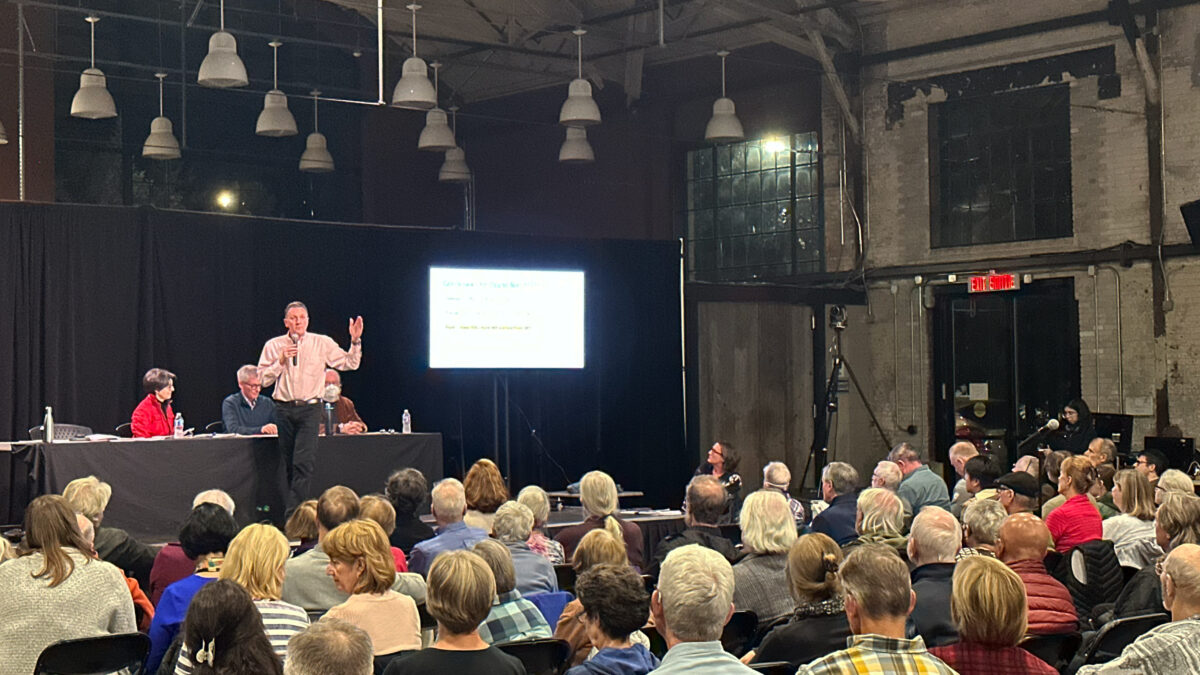

The final Lansdowne 2.0 project proposal will be at the finance and corporate services and the planning and housing committees for two days of discussion Nov. 2-3 and before city council on Nov. 10.