For Dawn Pickering, the Canadian National Institute for the Blind’s (CNIB) new charter of rights for children with visual impairments is a move to a better and more equal society.

“Shouldn’t we all do our best to try and work towards equity so that every kid has the same opportunity to thrive?” she told Capital Current. Her 11-year-old son, Ollie, lost his vision after a battle with cancer three years ago.

The CNIB recently released “A New Way Forward,” with three aims: increase understanding and awareness of the blind and visually impaired community; make journeys more accessible by eliminating barriers in public transport — from getting on the bus to finding the sidewalk; and supporting children with visual impairments in and out of the classroom.

“In developing this plan, we consulted with the largest number of Canadians who are blind, low vision or deaf-blind in Canada, in our history,” said Suzanne Decary-van den Broek, vice-president of the CNIB in central Canada.

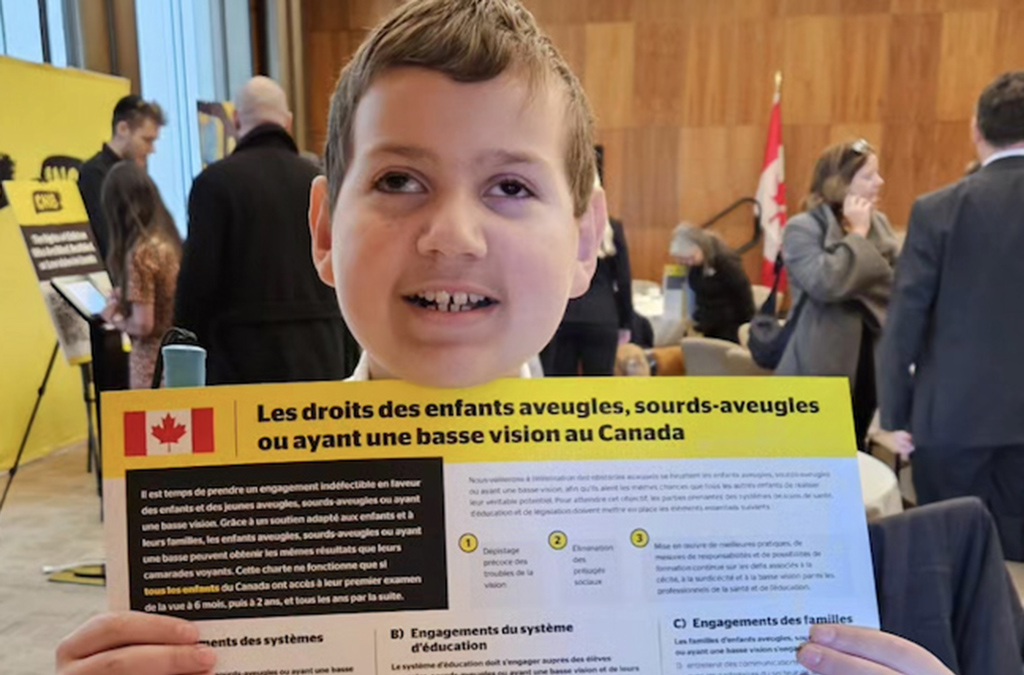

The CNIB unveiled the Charter of Rights of Children Who Are Blind, Deafblind or Low Vision on Nov. 20, the United Nations World Children’s Day.

One in 40 children has a visual impairment, and the charter says children have the right to an appropriate referral for support in education, health and in the community at the time of diagnosis.

“A lot of kids are falling through the cracks and they’re being left behind in the school systems and in their community,” Decary-van den Broek says. The CNIB hopes the charter raises awareness and leads to change. “There’s no reason for the world to not be an accessible place to anybody,” she said.

Andrew Galster, the executive director of CNIB Ontario, said the charter aims to address barriers in education and health care that are “major roadblocks” for children. He says many children don’t even know they are experiencing vision loss until they later get screened.

“The child doesn’t know what the child doesn’t experience,” said Galster. They may think their vision is blurry but “they’re not necessarily being flagged.” Prescribing mandatory eye tests before a child starts school would allow them to get the appropriate support from doctors and teachers and allow early intervention.

People “are tired of waiting, a lot of people have spent their whole life waiting for some of these changes,” said Galster.

Pickering, a member of the board of directors for Ontario parents of visually impaired children and an advocate for the CNIB, stressed the importance of having supports in place for those who are visually impaired, blind, deaf-blind and their families.

She says her family is lucky to live in Ottawa where there is access to the CNIB Hub and community support systems. The hub is a place for the visually impaired to meet and participate in various activities such as martial arts, ginger bread workshops, coffee and conversation. “It’s pretty phenomenal,” said Pickering.

Services in education, community and even health care differ from city to city but “it shouldn’t really matter … if you live here (Ottawa), or you live in a small town … you should be able to access services when needed.”

Pickering said that the CNIB showed her family many opportunities that were available and possible for her child.

Pickering’s family got a dog from the CNIB’s buddy dog program, learned braille and eventually participated in camps where her son, Ollie, had the opportunity to rock-climb, kayak, paddleboard and more. “It was really eye-opening for us. … He could engage with the world with just a little bit of adapted equipment, and do all the same things that he always liked to do when he was sighted,” Pickering said.

Pickering said the charter means that parents can begin to understand their children’s rights, especially in education and health. She stressed that all children have the right to have the same education as everybody else. “It’s not his fault he’s blind; he doesn’t get left behind just because he doesn’t have full vision.”