Clad in a paper gown, Tom Gardener was led into the emergency operation room with the instructions to not touch anything in blue. In front of him lay his partner, unconscious on the table and her stomach cut open, while he cradled their newborn daughter for the first time.

For 21 hours Gardener had been left alone in the hospital lounge as his ex-wife struggled through intensive labour before undergoing an emergency c-section. With no support from the staff, Gardener turned to the hospital janitor for help.

“I’m alone. There’s no one there. There’s nobody helping me,” Gardener said. “There’s no men’s support group. The woman I loved most and my baby — I didn’t know if they were gonna make it. I had no support.”

Services for fathers are often overlooked and under researched — particularly those that help with the transition to fatherhood during the perinatal period. Defined as the time during pregnancy and up to a year postpartum, the perinatal period is characterized by immense change for both parents and which can result in various mental health impacts. Unfortunately, paternal health is often neglected.

In an effort to increase support for fathers, Ottawa Public Health, in collaboration with McMaster University, will be providing free, nine-week, virtual cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) sessions this fall for fathers who are experiencing perinatal depression and anxiety.

“The focus is not so much on men during the perinatal postpartum period because we usually focus on the moms. So they may feel they don’t have their space in the healthcare system,” said Genevieve Mosher, a project officer nurse with the City of Ottawa.

“That’s why,” she added, “we’re trying to spread this message to make this more normalized.”

Offered through Parenting in Ottawa, a new resource for local parents created by OPH, these two-hour, weekly sessions will follow a manual developed by Dr. Ryan Van Lieshout, a professor of behavioural sciences and psychiatry at McMaster University.

Each week, participants will complete a module focused on different facets of communication and parenting such as social support and role transition.

The goal is to balance negative thoughts with positive ones using cognitive restructuring and psychoeducation techniques.

“As the group goes on we get into teaching them how to identify those negative thoughts . . . and how to make those thoughts more balanced,” said Van Lieshout.

“If you’re able to make those negative thoughts more balanced, it tends to produce positive shifts in the mood.”

What is paternal perinatal depression?

Paternal perinatal depression is a type of clinical despondency that coincides with the early stages of pregnancy to the first full year after the birth of a child.

The prevalence of paternal prenatal depression — the time between conception until birth — is just under 10 per cent. About nine per cent of fathers experience postpartum depression, which occurs up to a year after a child’s birth, according to a 2020 study in the medical science publication Journal of Affective Disorders.

“That rate in dads is about twice as high as other times in their life,” said Van Lieshout.

‘As the group goes on we get into teaching them how to identify those negative thoughts . . . and how to make those thoughts more balanced.’

— Dr. Ryan Van Lieshout, behavioural sciences professor, McMaster University.

Paternal perinatal depression can leave dads feeling powerless, overwhelmed, inadequate and resentful towards the child. Some may also experience somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbance or compulsive behaviours such as gambling.

“Sometimes it’s anxiety, other times some of them are feeling angry, some are feeling depressed, sad, anxious or worried, overwhelmed. So it definitely does vary,” said Mosher.

“We do see some different behaviours in what moms experience. For example some (fathers) may have some substance misuse which is not something we see often in moms.”

The signs of perinatal depression generally occur later for fathers than mothers, according to a 2019 study published in the journal Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. However, the risk of perinatal depression can increase for fathers whose partners are struggling with psychiatric problems.

According to CAMH, the Toronto-based Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, there is a 24- to 50-per-cent increased risk of depression and a 10- to 17-per-cent increased risk of anxiety among fathers whose wives develop mental health issues as new moms.

Other risk factors for paternal perinatal depression include the presence of depression prior to pregnancy, anxiety concurrent with pregnancy, significant adverse childhood experiences, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (widely known as ADHD) and being a victim of intimate partner violence, according to a 2021 study published in the journal Depression and Anxiety.

No Space for fathers? We’ll build our own!

In the months following the birth of Gardener’s daughter, Canada and countries around the globe descended into chaos as COVID-19 shifted from an epidemic to a pandemic. The new father’s world was upended. His stable home life dissolved with his wife’s choice to separate and his financial stability collapsed when he lost his job.

He wanted help. He searched for it.

“I went looking for it. I went to a program for fathers, for young men, and I was the only person there,” Gardener recalls. “The supports just aren’t there, or it isn’t accessible or widespread.”

Although the role of fatherhood is in transition, with fathers taking on greater active roles in caregiving, according to a 2022 report by Equimundo, healthcare services that engage fathers are lacking and gender norms are largely to blame for it.

‘I went looking for it. I went to a program for fathers, for young men, and I was the only person there. The supports just aren’t there, or it isn’t accessible or widespread.’

— Tom Gardener, member, Ottawa Dads Group

Traditionally, early infant care has been designated to and assumed by the mother, while fathers are seen as the “stoic breadwinner” of the family. This perception has continued to shape the landscape of services available to fathers at the macro (e.g. governmental), meso (e.g. organizational) and micro (e.g. clinician) levels of healthcare, according to a 2024 Australian-led, international meta-analysis published in the journal Midwifery.

Fathers in the study reported “father unfriendly” or “hostile environments” due to restrictive gender norms such as the “perceptions of ‘women’s work’” which created maternal-centric healthcare services that often excluded father engagement.

“Men often feel that they are excluded or invisible, so there is that stigma when it comes to accessing care because they feel like, ‘Well there’s really not much available for me,’ ” Mosher said.

During his search, Gardener stumbled upon a Facebook group, the Ottawa Dads Group. While the group’s nature was not clinical, the community it fostered helped Gardener immensely.

“There’s not a lot of men’s mental health support out there. So the group did help,” Gardener said. “These struggles that I’m going through are not unique to me, so it felt good to talk to people. I made very good friends. Deep friends.”

When he joined ODG, Gardener felt there was little conversation or community. Many of the posts were often ads for services and there were few discussions for advice or support.

“This is not a community.” Gardener remembers thinking to himself. “So I did things like you can only do business posts once a month. I’ve opened up side chats for different circumstances, for single dads, gay dads, military dads, Christian dads.”

“Men’s mental health is not going to be solved through 1-800 numbers,” said Gardener. “It’s going to be solved by community, friendship and meaningful relationships.”

While more fathers are open to discussing their mental health difficulties with their partners, the stigma associated with help-seeking behaviours can hinder men from reaching out, according to a 2021 British-led study in the journal Mood Disorder. The vulnerability associated with mental health difficulties paired with the need to be “the strong person” in the relationship can cause feelings of weakness or threaten a man’s masculinity.

“Paternal perinatal depression is often not really detected or shared because (fathers) don’t often reach out for support,” said Mosher.

That study also found fathers expressed worry that their mental health needs would compromise the support given to women by becoming an unnecessary burden to healthcare services.

Despite these perceptual barriers, the study found men were open to receiving more information on signs of paternal depression and the triggers that cause it, with the belief that greater awareness would reduce both clinical (e.g. healthcare services) and individual (e.g. self-perception) barriers.

Gardener is only one of many fathers trying to generate discussion around paternal depression.

Mark Williams, a father and parenting advocate from the U.K., said he experienced his very first panic attack in the labour ward as his wife endured 22 hours of childbirth. His son was born in December around Christmas. The nights were longer and Williams found himself at home more often.

At the time his wife was experiencing severe postnatal depression, which prompted Williams to step into a greater supportive role for his partner and led him to give up his employment position. While he put on a brave face, the reality was that he was struggling, too.

“I was wearing a mask. You know anyone who knows me, I’m always smiling and joking, but deep down I was struggling inside.” said Williams.

“The first six months were a vital time when I was home. But I think my mental health — I started feeling guilt. ‘Am I good enough as a dad?’ I haven’t got a job. I can’t provide like I used to’.”

Four years after the birth of his son, Williams finally reached out for support following the loss of his grandfather and his mother’s cancer diagnosis. The stress and grieving pushed him over the edge. Soon he developed a dad’s support group, Fathers Reaching Out.

From there his advocacy work quickly ramped up as Williams wrote articles, appeared on talk shows and radio programs and collaborated with Dr. Jane Hanley, a perinatal mental health specialist and president of the International Marcè Society for Perinatal Mental Health.

“When I first started there were a lot of trolls — only because people were thinking I was taking attention away from mums,” said Williams.

‘The father is not always the breadwinner anymore. It’s the mum who has to go work and the father’s home. If the father’s home alone with the baby and he’s not getting the support, of course that’s gonna have an impact on that child, as well.’

— Mark Williams, co-founder, International Father Mental Health Day

In 2020, Williams was a keynote speaker for a TEDx talk on “The Importance of new fathers’ mental health”. He also co-founded International Fathers Mental Health Day with Dr. Daniel Singley.

“There’s little on policies to actually include fathers. But we need better pathways of care and when you get better pathways of care, health professionals are more likely to engage with fathers,” said Williams.

“The father is not always the breadwinner anymore. It’s the mum who has to go work and the father’s home. If the father’s home alone with the baby and he’s not getting the support, of course that’s gonna have an impact on that child, as well.”

Cognitive restructuring

In Ontario, “treatment as usual” for fathers with perinatal depression often involves the use of medication, such as antidepressants. In some cases men may also receive psychotherapy, but this can be difficult to obtain through the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, explained Van Lieshout.

“Treatment as usual could involve the use of an antidepressant, usually a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor — an SSRI, usually sertraline or escitalopram. But most dads, we think, actually go untreated,” said Van Lieshout.

Through his investigation with a sample of 141 mothers, Van Lieshout found the integration of usual treatments, such as medication, with CBT interventions, significantly reduced the symptoms of postpartum depression compared to only taking the usual treatments without CBT.

“It sort of capitalizes on the fact that people in the perinatal period can have more negative thoughts about themselves, about other people and about the future,” said Van Lieshout.

Unfortunately, the efficacy of CBT interventions among fathers with perinatal depression is not well known.

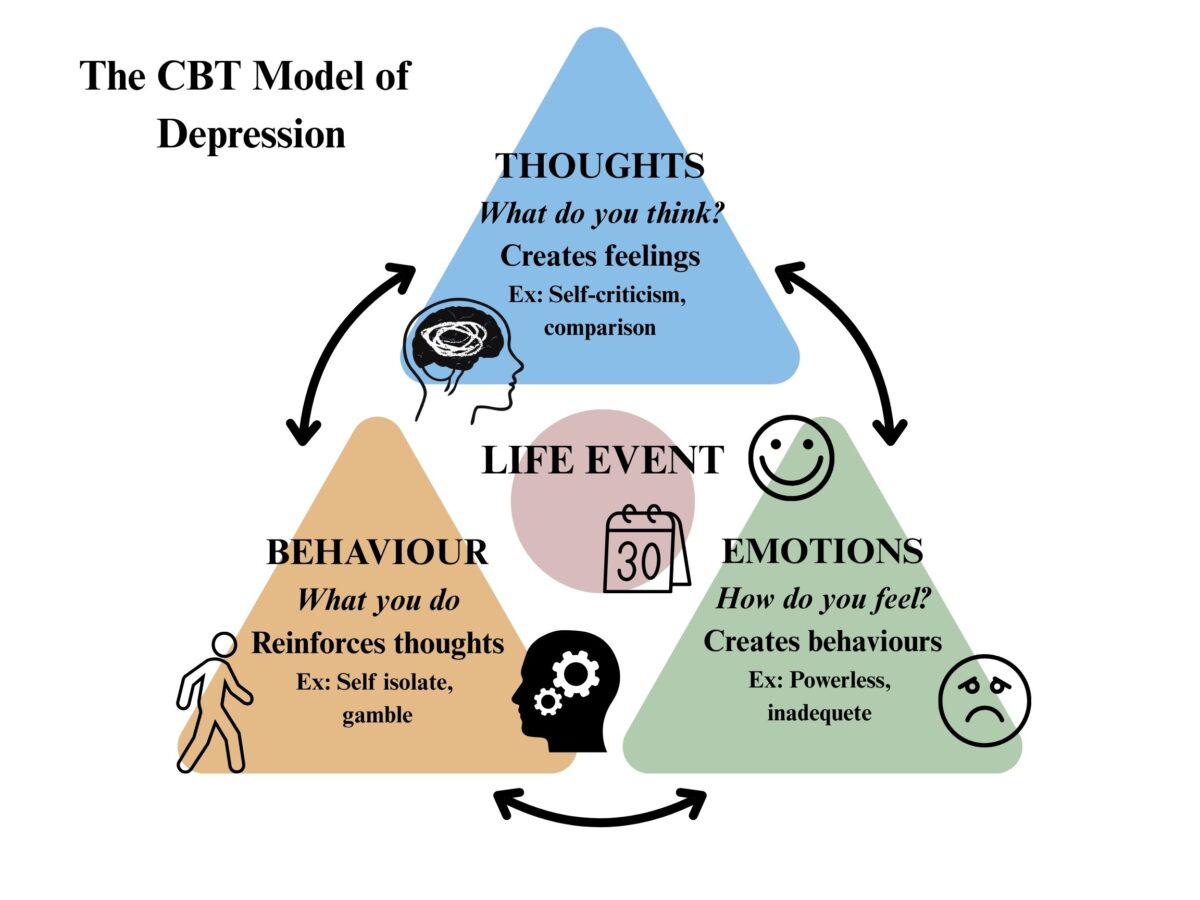

Within depression, there is a proposed model of cognitive behaviour, the cognitive behavioural model of depression, which suggests the negative perceptions we have on life events can manifest in maladaptive behaviours, which leads to dysfunctional cognitive reactions. These reactions can then create the symptoms associated with depression.

CBT interventions aim to restructure this thought pattern through the use of “thought records”. Thought records are tools used to examine, identify and reframe negative thoughts. They involve the recording of emotions and thoughts associated with a situation. Then, using different restructuring techniques, like the evidence technique, which focuses on the examination of evidence that contradicts and supports a thought, the person will challenge those negative thoughts.

“We have this cycle of negative thoughts, strong negative feelings and avoidance and withdrawn behaviours,” said Van Lieshout. “CBT aims to break the cycle at two places — the thoughts and the behaviours.”

Eligibility

During the last half of 2024, Parenting in Ottawa launched the first nine-week CBT sessions for mothers in both French and English. These session finished during the last quarter of the year with resounding success.

“Overall the feedback surveys are showing that moms are feeling better emotionally,” said Mosher. “We are getting a really great response from the community. We are getting many, many referrals. So it’s been really great. It’s been such a positive experience and we’re also noticing there is a need for this.”

In order to participate in these free nine-week sessions, fathers must pass certain eligibility criteria. Fathers must be at least 18 years old, have a child 18 months old or younger, or are expecting to have a child, there should be no other major mental health concerns and they need access to technology.

‘Something happens when men have the courage to be vulnerable — it enables other men to be vulnerable.’

— Tom Gardener, member, Ottawa Dads Group

Fathers must also pass the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale, with a score of nine or more. The maximum score is 30. The scale is a clinical screening tool often used for mothers at risk, or showing signs of postnatal depression.

“Making sure that all these services are available has an impact on the population.” Mosher said. “Having strong fathers in the community, healthy fathers — emotionally physically — has an impact on families and on the future of children.”

As he continues his journey through fatherhood, Gardener has been slowly restructuring his own relationship with masculinity and what it means to be a man. The invulnerability that boys, men and fathers have been groomed to show is what Gardener believes creates the barrier to reaching out.

“Something happens when men have the courage to be vulnerable — it enables other men to be vulnerable,” Gardener said. “Everything you think about being a man — strong, tough, doesn’t cry, all that sort of stuff — and then what do you need in a helpful friend? None of that.”