What’s it like to eat in complete darkness without even the light from your phone to guide you? You can find out inside the Dark Fork restaurant in the ByWard Market.

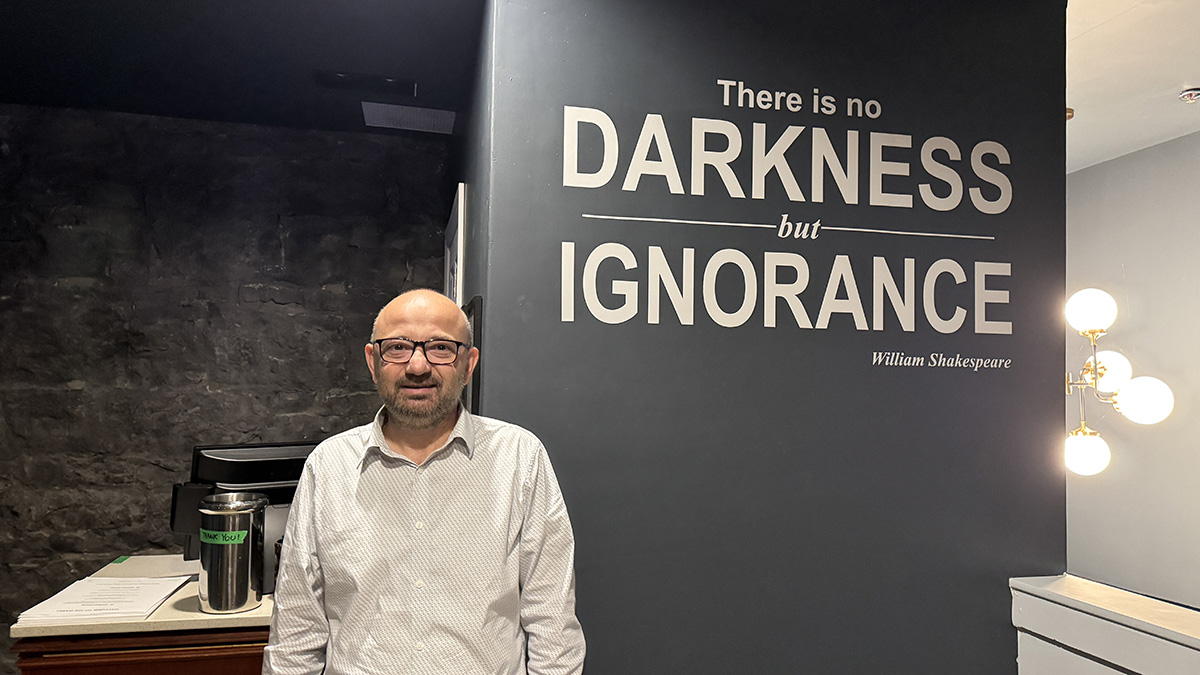

The dine-in-the-dark restaurant, which opened last month, is the creation of Moe Alameddine. The Lebanon-born entrepreneur, who grew up in this city, opened Canada’s first dark dining restaurant, Montreal’s O.Noir, in 2006, followed by locations in Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary (Calgary’s is now closed). Alameddine recently sold his share in those ventures to focus on Dark Fork in Ottawa.

The response to its opening has been better than he expected, he said.

“I remember when we opened in Vancouver [12 years ago], the opening week wasn’t as busy as Ottawa’s opening week,” he said. He thinks this is mainly because of the attention Dark Fork has been getting in the media.

On our excursion to the restaurant, we opted for a three-course meal. A hostess first sat us in a lit room, where we ordered steak frites from the menu (the other choices were crusted chicken parmesan, pasta San Marzano basil sauce, fish of the day or a surprise dish. Appetizers and desserts remain a mystery before eating). Then, like other guests, we checked our bags and phones into a locker. Clutching our server — who was visually disabled, as all the servers are at Dark Fork — we passed through two heavy curtains into darkness.

Most of Dark Fork’s staff applied for work here through announcements Alameddine made with help from Canada’s National Institute for the Blind. Alameddine said he wants his customers to have a “unique dining experience” and to trust the blind servers by giving them a chance.

“We give them the opportunity to do the job,” said Alameddine. “It’s a very tough industry, so I broke the barrier and I put them to work.”

Our first few steps into the dining room were disorienting. We held on tighter to each other and asked each other if we were OK. A couple seated nearby — we couldn’t see them — called out “Hi!” We all laughed.

As time went by, we started to notice muffled conversations at nearby tables. We could also hear servers giving the same instructions to other guests that they they had given us earlier.

Eating in the dark was challenging. Fries slipped off the plate more than once, and one of us lost the napkin. The waiter seemed used to this. The experience forced us to rely on touch and feel. We were poking around the plate with our hands for each bite and were careful not to knock over the drinks. The kitchen had pre-cut our steak, but that didn’t stop it from falling from time to time before it made it to our mouths.

The darkness did seem to heighten our sense of taste and texture. The steak’s black pepper sauce seemed stronger and more tasteful. The smell of the food was more intense in the dark, since we couldn’t see what it looked like.

As we ate, we kept asking each other, “Are you there?” We couldn’t see across the table; all we heard was the sound of forks and plates, so we needed confirmation that we still had company. Even when calling our server, there was no waving him down or raising a hand; we had to call his name out into the darkness and wait for him to assist us.

By dessert, we were much more comfortable, and quickly realized we were having chocolate cake. We never lost our waters, iced tea and Diet Coke, but it was hard to judge how much was left in the glass.

Hill Goldberg, a first-time customer at Dark Fork, said dining in the dark brought back memories of his university days. Back then, he worked with blind students at the Montreal Association for the Blind, but he didn’t know what it was like to be visually impaired.

“It pulls out all your senses,” Goldenberg said. “This was amazing … it shows you the senses you have, like feelings and things like that.”

He added, “I would come back in a heartbeat.”

Andrew Riff, who dined with Goldberg, said some friends recommended Dark Fork.

“It really made you think about what you’re smelling and hearing,” Riff said. “I ended up eating with my hands because every time I used my fork, I got nothing.”

“It really made me think about what I was eating and not looking at my phone,” Riff said. “I thought I’d be kind of anxious about it, but I think it was a good thing.”

The locations of dine-in-the-dark restaurants across Canada. [Map @ Samantha Carrillo Brito].

“[We want] to make a landmark in this city, an institution,” said Alameddine. “We want people to point their finger to the place and recognize it.”

The restaurant owner wants to get rid of the notion that “Ottawa is boring” through the development of his business and others like it. He is sharing the phrase “Ottawa mon amour” through a hashtag on social media, and by adding it to staff shirts.

“This concept here, it’s in Paris, London, L.A. and now Ottawa. If it was boring then we wouldn’t come here,” he said.

The owner says the city is trying to attract people and projects like his to the city. He said Ottawa needs this, considering it has a low number of restaurants per capita.

According to an article by Snappy, Ottawa is home to 1.9 restaurants per 1,000 residents, the lowest among the six largest Canadian cities.

Aaron Prevost is a visually impaired server at Dark Fork. He worked for more than two years at the dark dining location in Calgary before it closed.

Now living in Ottawa, Prevost trained many of the servers at the restaurant. He says the training process ranges from two weeks to two months.

“Basically we teach everyone to follow guided lines. So here we have some carpet or some places even have a little rope that most people wouldn’t even notice. Just things to help keep the servers on track,” he said.

He added that he usually hands people their drinks to prevent spilling. He makes sure the guest is holding the cup before letting go himself.

The server also focuses on communication with his customers when going into the dining room. He said this is especially important when guiding people into the dark area.

“[Guiding customers through the curtains] seems easier than it actually is, because you gotta make sure that the outer curtain is closed before you open the inner one, otherwise you light up the dining room,” he said.

Prevost enjoys meeting different people throughout his job. He also takes advantage of the opportunity to answer customers’ questions about blindness.

After 90 minutes in the dark, we again clung to our server as he guided us back to the light, a jarring transition. After paying at the same spot where we had ordered, we reflected on the sensory experience that had challenged our usual way of dining. We left Dark Fork wanting to share our adventure.