After the worst wildfire season ever in Canada, some provinces are exploring the use of AI to better predict fires. But experts warn that the destructive season highlights the need for better coordination across the country and more resources to actually fight fires on the ground.

In 2023, Canada recorded more than 6,000 fires that burned more than 16.5 million hectares, which, according to Natural Resources Canada, is an area larger than Greece.

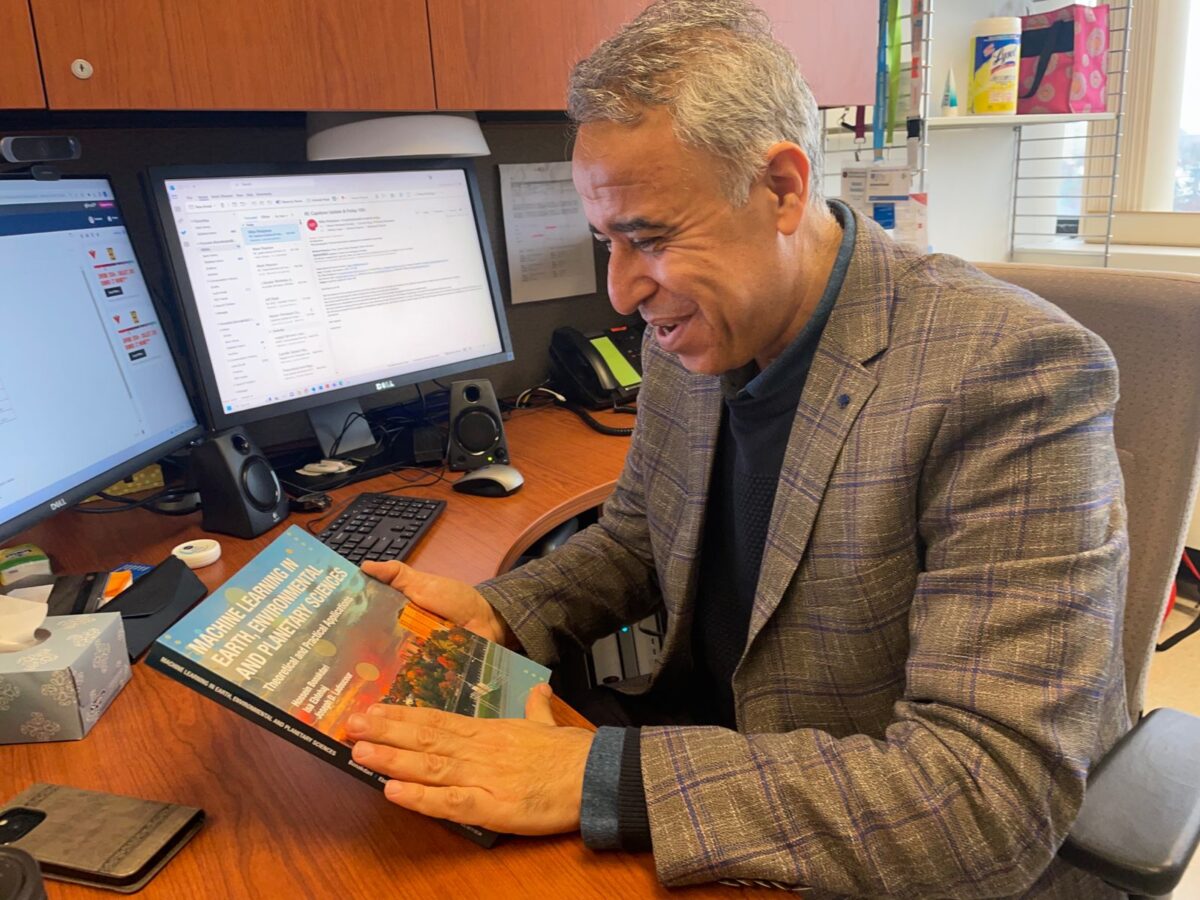

Dr. Mostafa Farrokhabadi, an assistant professor at the University of Calgary’s Department of Electrical and Software Engineering, said this stage of climate change leaves problem-solvers in “firefighting mode.”

“That means we have to throw whatever resources we have on the problem,” said Farrokhabadi, who specializes in innovative climate change solutions.

Artificial Intelligence is one of those potential solutions.

Provinces are already pairing with leading companies in telecommunication and artificial intelligence technology to find ways to predict, prevent and adapt to future wildfire seasons.

On Sept. 19, Microsoft announced a year-long collaboration with Alberta and AltaML, an Edmonton-based company, to help predict wildfires.

And while not based on AI, Rogers Communications has announced a collaboration with the University of British Columbia and the B.C. wildfire service to predict remote fires using Elon Musk’s SpaceX technology.

While some experts explore the potential for these tools to be shared across Canada, others argue different strategies should take precedence.

A nation-wide solution

As provinces make headway independently, Canada needs a national alliance consisting of federal and provincial governments, university experts and telecommunication and AI software companies, said Houssain Bonakdari, an associate professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of Ottawa.

“If we have a model that works in B.C, why not adjust it for Quebec?” He said, “Right now everyone is doing something separately.”

Bonakdari said that, while universities have expert knowledge, they need governments to build infrastructure and telecommunication companies to install sensors that collect information — including on humidity, wind, temperature — in high-risk areas, which are then fed into artificial intelligence systems.

In an email to Capital Current, John Weigelt, a national technology officer at Microsoft Canada, agreed that sharing information is important, adding that “Microsoft is a strong supporter of shared solutions.”

“Since Canada’s public sector has a long history of working together using shared solutions, we are optimistic that these solutions will be shared to find use in other regions,” Weigelt wrote.

More investment needed

The president of the Ontario Professional Association of Wildland Firefighters association, said this wildfire season in Ontario was marked by a lack of adequate resources.

“We’re supposed to have 190-200 fire crews. We only had 142 this past summer,” said Eric Davidson, who has worked as a firefighter for the past 10 years. “It’s getting to the point where we almost have to stop hiring because we don’t have enough leadership roles to hire enough people to fill out the crews.”

Davidson added that while this fire season was not the worst Ontario has seen, it exhausted their resources to “a level that was worse than a record breaking year like 2021.”

He said the deficit resulted from a combination of things, including challenges with firefighter retention, aging equipment and demands to fight fires in different provinces.

The Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, a not-for-profit corporation that coordinates resource sharing between provinces and facilitates wildfire cooperation nationally, told Capital Current in an email that Canada spent 120 days of the fire season at preparedness level 5, the highest level of wildfire activity. This level is allocated when several areas across the country face large wildfires that tax resources and require interprovincial or international collaboration.

Davidson says he welcomes any technology that will help make firefighters’ jobs easier, adding that he would ‘love’ to see an alliance on the national level.

But, the federal government must also prioritize investing in firefighters and resources, including newer water bomber planes across Canada, Davidson said.

“You can spend all this money on tech, AI and drones,” he said. “But if we don’t have any firefighters left, then it doesn’t matter if you tell me a fire is going to start tomorrow because nobody is going to go put it out.”

AI isn’t a perfect solution

While AI has potential for wildfire prediction, the emerging technology still has limitations. Currently, it is able to predict wildfires just one day in advance, with some problems with accuracy.

But Weigelt said that 80 per cent accuracy in wildfire prediction is ‘huge’, and that improvements will come with time.

No matter what the pitfalls, any emerging solution related to climate change should be explored and shared, Farrokhabadi said.

“The solution to the problem requires an astronomical amount of innovation,” he said. “I don’t think it’s one way or another, I think everyone should come together and contribute to the solution.”

Collaborative models for combating climate change are already active across the country.

Mostafa Farrokhabadi chairs the Innovation Ecosystem for the U.S.-Canada Centre on Climate-Resilient Western Interconnected Grid, an international and interdisciplinary partnership the Universities of Utah and Calgary spearheaded in the fall, 2023.

The Centre focuses on a variety of solutions across disciplines to enhance climate change-resiliency, and the Information Ecosystem focuses in part on commercializing the technologies it develops. Many of those technologies are based on AI and machine learning methods, he said.

“I wouldn’t say AI is necessarily the biggest component of the centre, but it’s definitely one of the most important components.”

He said one important function for AI at the Centre would be making sense of wildfire data in the electrical and environmental domains. It would help experts better understand the impacts wildfires and the electrical grid have on each other.

The regions and affiliates included in the U.S.-Canada Centre were mainly determined by the physical boundaries of the Western Interconnected Power Grid. However, their vision is to expand collaboration across the US and Canada within the next few years, Farrokhabadi said.

“The problem doesn’t have a jurisdiction. Climate-driven extreme events are a global problem at this point,” he said. “We invite everyone to collaborate.”

For Farrokhabadi, combatting the impacts of climate change requires an international and interdisciplinary collaborative model.

“Without total collaboration, without everyone realizing their share and without everyone contributing to the problem, it’s not going to solve itself.”

Correction: This story has been updated since the original version, which identified Dr. Mostafa Farrokhabadi as an associate professor. He is an assistant professor.