By Nadya Pankiw, Brendan Skykora, and Sarah Tsounis

It’s unknown how much greenhouse gas is produced by Ottawa’s existing buildings, but one organization is preparing to find out.

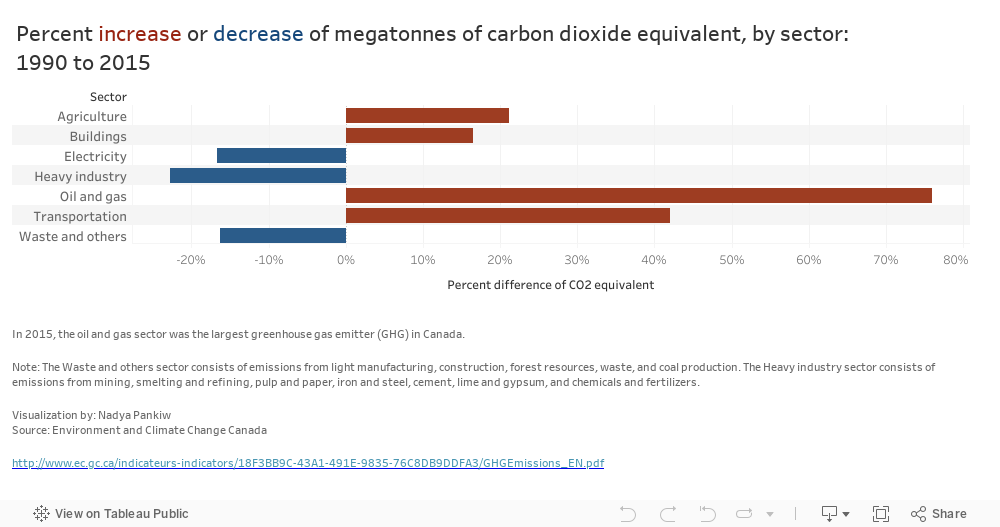

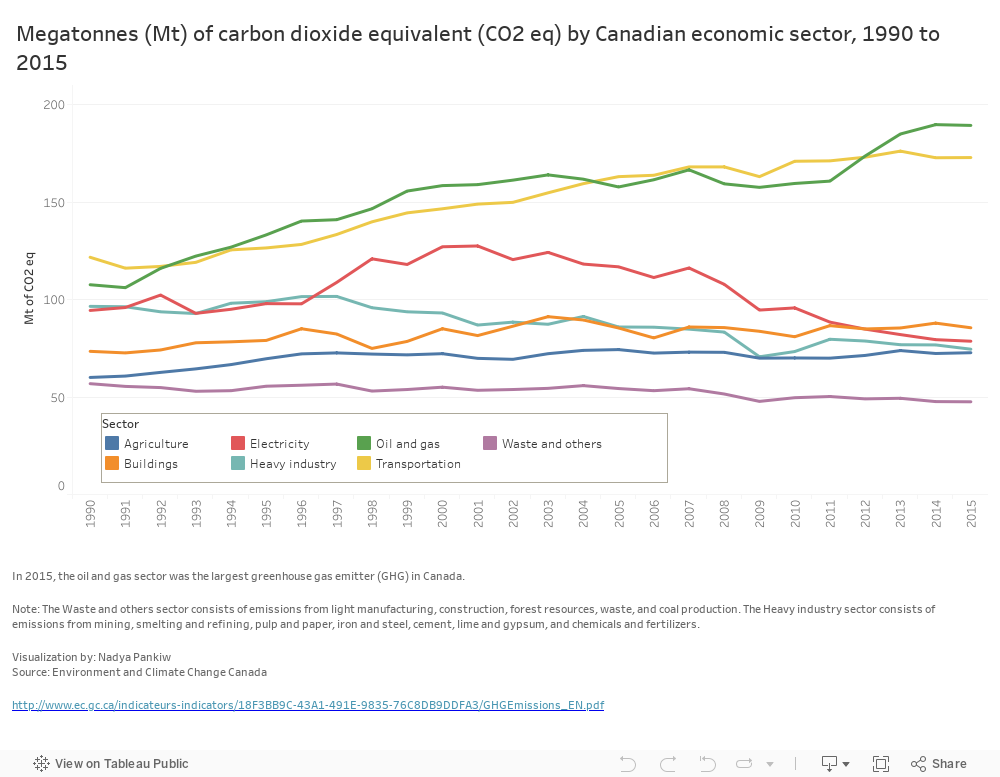

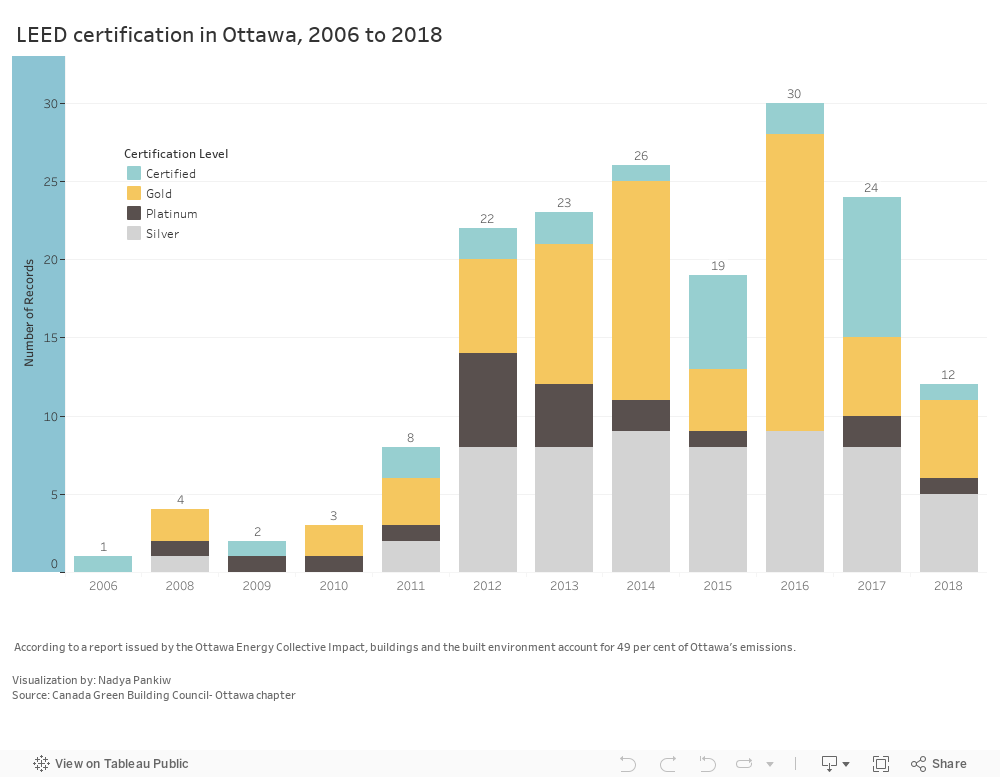

According to a 2017 report by Ottawa Energy Collective Impact — a group of green organizations and advocates in the city — buildings and the built environment accounts for 49 per cent of the city’s emissions. That’s nine per cent higher than the second biggest culprit: transportation.

Beginning in the fall, the Ottawa chapter of the Canada Green Building Council plans to collect information from national organizations and the city’s utilities department to assess the carbon intensity of Ottawa’s built environment. The end goal is to produce more informed policy recommendations for cutting the carbon output, such as how to go about retrofitting older, more inefficient buildings.

“What we need to do now is take a better inventory of our building stock, and try to understand it not just in terms of energy consumption but in terms of greenhouse gas emissions,” said Kim Bouffard, manager of the council’s Ottawa chapter.

Bouffard says this will be her organization’s main work into 2019, and hopes the results will set an example for the rest of the country.

“I think it’s so important that as the capital we really take a lead on this.”

The plan follows some stark revelations about the looming threat of climate change made in a report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in early October. The report gave the world 12 years to hold the global temperature increase to 1.5C, a threshold above which extreme weather events and other changes will worsen.

The chapter is part of Ottawa Energy Collective Impact, which works alongside the city’s energy evolution program. Ottawa, like Ontario, has signed on to emissions reduction targets of 80 per cent of 2012’s levels by 2050.

College Ward councillor Rick Chiarelli confirmed that there’s been “hardly anything done” in terms of targeting the emissions of existing buildings in Ottawa. The vice chair of the environment committee said the city’s main focus is on new construction, since it’s easier to build sustainable buildings from scratch than to retrofit older buildings.

For Bouffard, the fact that buildings make up nearly half of Ottawa’s total emissions is just one reason to view the built environment as the industry most suitable for targeted reduction strategies.

“When you look at all these different industries, the only one that has the tech and can do it while making money is the built environment, so we kind of have to lead the way.”

The Green Building Council is in charge of giving building projects in Canada certification for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), which ranges from basic to platinum certification depending on a lengthy list of sustainability standards. Bouffard says that while the added focus on existing buildings is critical if Ottawa is to meet its emissions reduction targets, designing new buildings according to LEED standards is still equally important.

“If you’re trying to hit targets by 2030 you can guarantee that at least 50 per cent of the buildings that exist now are going to exist at that time, so you’ve got to understand how they’re performing. But you also have to make sure that all new builds are built towards zero carbon.”

On a smaller scale, some businesses in Ottawa are taking their own measures to track their greenhouse gas emissions.

Angela Keller-Herzog runs her bed and breakfast business from her Glebe home, which was built in 1898. In 2015 she became a member of Carbon 613, a local green network of that provides emissions tracking tools and software to its members.

“It’s interesting to have organizations that can help us with measurement and the knowledge that is helpful for making rational decisions about carbon.” Keller-Herzog said she’s in the early stages of having solar tiles installed as part of a pilot project.

“That’s a good example of how, even though I have just a micro-sized business compared to some of my colleagues [at Carbon 613], I can be helpful.”

“Climate change is the issue that our generation of people needs to step up to, and so we all need to do our bit, whether that’s as individuals or as businesses or as advocates,” said Keller-Herzog.

To that end, Bouffard hopes the Green Building Council’s focus on quantifying the carbon footprint of the city’s buildings will lead to a clearer way forward for people and businesses wanting to retrofit, and also pave the way for more robust city-wide initiatives.

“Once you have that information then it’s easier to create a more concise plan of how to move forward,” Bouffard said.

So far this year, 12 building projects in Ottawa have received LEED certification. That’s down from 24 last year and 30 in 2016. Only four of the certifications in 2018 were for existing buildings.

Ontario is now in the middle of a five-year plan to reduce greenhouse gas pollution, but the previous Liberal government’s plan has undergone significant changes since Premier Doug Ford’s government took over the reins.

Ford has repealed the cap-and-trade carbon market system after the Progressive Conservatives passed legislation on the last day of October. Cap-and-trade was a major initiative of the Liberals’ five-year plan that aimed to put limits on the amount of carbon companies can emit before having to buy allowances from other companies that stayed under the cap.

In June the provincial government nixed a program that provided rebates to homeowners who made energy-efficient renovations – a program funded by the cap-and-trade system.