When Ottawa Council recently approved plans to include surrounding streets in a major study of transportation options along Bank Street, advocates for public transit, cyclists and pedestrians dismissed the move as a waste of time. Instead, they argued, an obvious solution to the congestion and safety issues — 24-hour bus lanes — should be implemented urgently.

The Bank Street Active Transportation and Transit Priority Feasibility Study is an ongoing initiative by the city to analyze and improve the complicated relationship between cyclists, pedestrians, buses and vehicle traffic on Bank Street, one of Ottawa’s main north-south arteries linking the urban core and suburban Ottawa South.

The study has been going on since February 2024, and could now see delays with the inclusion of additional streets.

But Strong Towns Ottawa, an urbanism advocacy group, said so many problems would be solved with 24-hour bus lanes that firm action is needed now instead of further analysis.

“At a certain point, we have to stop studying things and just do them,” Marko Miljusevic, a director of Strong Towns Ottawa, said at the city’s May 22 public works and infrastructure committee meeting. “We cannot keep delaying the improvement of a vital transit corridor, especially when the city is worried about ridership numbers.”

Strong Towns Ottawa then took its message to Bank Street, as its members pooled money on May 29 to rent out the sign at the Mayfair Theatre — near the corner of Bank and Sunnyside Avenue — to promote bus lanes.

Bank Street is the busiest bus corridor in the city, as the No. 6 and 7 lines are two of the top three most ridden routes in the city. According to City of Ottawa internal data, the two bus routes regularly combine for more than 100,000 riders per week.

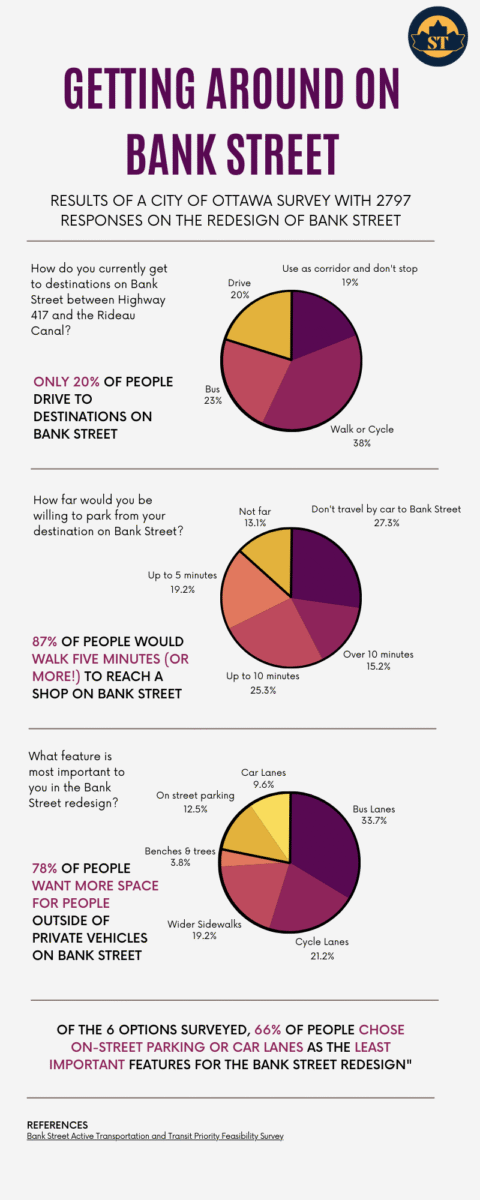

As part of the feasibility study, the city posted an online survey last summer to determine what people wanted to see from a Bank Street redesign. The most popular answer was bus lanes at nearly 34 per cent of responses, while 78 per cent of respondents wanted more space in general for non-vehicle options.

Derrick Simpson, a member of Strong Towns Ottawa who also chairs the Centretown Community Association’s transit board, said the survey results echo the concerns of residents he’s spoken to.

“We hosted a poll with all of the members of the Centretown Community Association’s transit committee, and a lot of options were on there,” Simpson said. “The one that was voted the top priority was bus lanes on Bank Street and trying to fix transportation on Bank Street.”

Simpson also believes that bus lanes could help the city financially.

“What has us optimistic is that it wouldn’t cost a lot of money to do this fix,” Simpson said. “We think that in the long term it would save the City of Ottawa more money as the buses would run more reliably and that could lead to more ridership, which would increase money in the fare box.”

Bus lanes and safety concerns on Bank Street

Many safety concerns have been raised recently regarding Bank Street, especially concerning cyclists. Recently, the safety concerns of cyclists were brought to the forefront following an accident on the street in the South Keys area that resulted in the death of a cyclist.

Despite this, Strong Towns Ottawa is still pushing for prioritized bus lanes over bike lanes, largely due to a lack of alternatives for transit riders.

“Bank Street is the only street that actually goes north and south past the canal and river,” Miljusevic said. “You can’t pick a different street to put buses on because they don’t go to any of the other streets, whereas at the very least, cyclists have that option.”

Miljusevic says that he normally walks and cycles as opposed to taking transit down Bank Street these days, but still believes in prioritizing the bus lanes. He says bus lanes would be safer for cyclists as a lane without cars would prevent riders from getting hit by doors.

“If you’re a cyclist and you’re fairly comfortable cycling at 15 to 20 kilometres an hour, you can stay ahead of a bus because it’s stopping and starting every couple of minutes,” Miljusevic said. “So even the bus lanes would be an improvement over what is in the area for cyclists right now.”

‘At a certain point, we have to stop studying things and just do them. We cannot keep delaying the improvement of a vital transit corridor, especially when the city is worried about ridership numbers.’

— Marko Miljusevic, board member, Strong Towns Ottawa

Miljusevic adds that the replacement of parking on Bank Street could make it safer for pedestrians, especially at crosswalks without signals.

“When you have parked cars on the road, it’s extremely difficult for you to be able to tell when to cross,” Miljusevic said. “So, having a bus lane instead of parking that would block vision would allow everyone to be able to actually see what’s happening on the street.”

“Peak” Hour Bus Lanes

The city’s proposals for Bank Street have a focus on improving bus service at peak transit times.

However, according to Miljusevic and Strong Towns Ottawa, there are plenty of issues with peak-hour bus lanes.

“Only having bus lanes during small sections of the day leads to confusion — and tickets — for drivers,” Strong Towns Ottawa says on a page dedicated to Bank Street transit. “Many studies also show that temporary bus lanes gain none of the advantage of full-time bus lanes as there are too often cars remaining parked in the lanes; this ends up leading to none of the benefits you’d expect from bus lanes.”

The Centretown Community Association agrees with this argument. Simpson says the group supports 24-hour bus lanes.

The main concern about bus lanes comes from local businesses, who fear the impacts of losing business if parking spots are removed.

In the Glebe, there are 143 on-street parking spots. According to Strong Towns Ottawa, this only accounts for 7 per cent of all parking near Bank Street.

“Given that there are plenty of underused parking spots available in the surrounding area, it makes sense to move the parking to those other locations to free up such vital space in an extremely important corridor for our city,” Strong Towns Ottawa states on its website.

The city plans to present some initial findings and recommendations of the feasibility study in early 2026. While many await to see the conclusions the city comes to regarding Bank Street, Miljusevic, Simpson, and their respective organizations want solutions implemented now.

“The longer we delay, the worse the situation gets with our transit and the more it will cost the city to do, which is something we can’t afford to do given our financial situation,” Miljusevic said.