When Winnie-the-Pooh starred in the 2018 Disney film Christopher Robin, young families turned out in droves to watch as the beloved bear with the “rumbly tumbly” was reunited with the title character as an adult, and the two rediscovered the joys of childhood wonder in the Hundred Acre Wood.

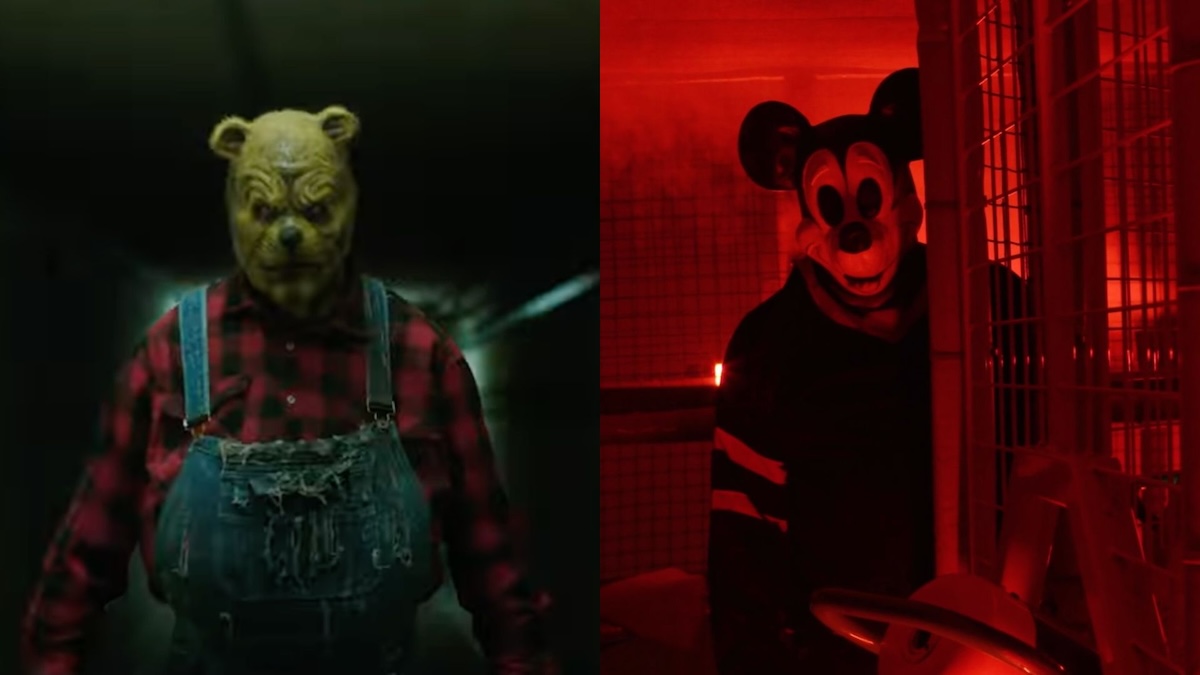

But in the newest films starring Winnie-the-Pooh, the bear is out for murder as he and the rest of the Hundred Acre Wood crew find victims to feed on after being abandoned for years. He no longer looks like a “silly old bear” — he’s actually a human wearing a red plaid shirt with overalls and a frightening yellow bear mask. He’s also wielding a knife.

This is the plot of the independent horror film series, Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey, with the first instalment released in January 2023. The century-old characters from the original book by British children’s author A.A. Milne became part of the public domain in 2022, making such adaptations legal.

A sequel followed this past March, despite the negative reaction the first film received. However, the second film, which had a larger budget and revamped Pooh’s murderous visage to resemble an actual bear, got slightly better reviews. Shortly after, a third film was announced with an even broader embrace of beloved characters from children’s literature given nightmarish makeovers.

It’s honing in on something that we find completely hard to believe. That’s the appeal of this, right? The shock value is increased by the use of these familiar characters from many people’s childhoods.

— Julie Garlen, childhood and youth studies professor at Carleton University

The filmmakers behind Blood and Honey revealed plans to release a horror film in 2025 titled Poohniverse: Monsters Assemble. The film would feature murderous versions of the “Winnie-the-Pooh” bunch along with other twisted incarnations of public-domain children’s characters such as Bambi, Tinkerbell, Pinocchio and more. The British studio behind the film, Jagged Edge Productions, also plans to make movies starring each of these characters separately.

Another famous character associated with Disney that joined the public domain this past January was none other than Mickey Mouse. However, only its earliest version from the short 1920s-era film Steamboat Willie became available. Not long after the copyrights expired, a slasher film featuring the titular rodent, Mickey’s Mouse Trap, released its first trailer. The Ottawa-based film so far has no set release date.

These types of movies have been surprisingly successful, making headlines around the world and attracting large audiences. For example, despite having a shoestring budget of under $50,000 and being named “Worst Picture” at the 2024 Golden Raspberry Awards, Blood and Honey generated more than $7.7 million US worldwide at the box office.

The reason? Because adult audiences have strong bonds with these characters and value the memories they hold — even when reimagined for the horror genre.

“It doesn’t surprise me that people would take these very familiar characters and do something perverse with them, because I think it intensifies the thrill of producing some kind of horror content,” said Julie Garlen, a childhood and youth studies professor at Carleton University.

“It’s honing in on something that we find completely hard to believe,” she said. “That’s the appeal of this, right? The shock value is increased by the use of these familiar characters from many people’s childhoods.”

These films may be thrilling for adult audiences, but what about children who admire these endearing characters? In an age of social media and streaming services, accidental exposure to the new horror trend is hard to prevent, observers say.

One such incident made headlines last October after a teacher in Miami Springs, Florida reportedly showed a fourth-grade class Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey without checking its content warnings. He allegedly allowed the students to pick the movie, and let it run for more than 20 minutes before turning it off after students became upset. The Academy of Innovative Education subsequently told CBS News that it had to “take appropriate action to ensure the safety and well-being of students” and provided counselling for students troubled by the incident.

Matthew Johnson, director of education for the digital literacy non-profit, MediaSmarts, said teenagers and adults may find horror movies exciting since they understand the context and have an underlying sense of safety. For younger children, it’s more challenging.

“If you’re not ready for it, if you’re seeing things where you don’t have the context, where you don’t have the things that provide security for you … then you get the pure fear response.”

Johnson points to research on the long-term impact of fear experiences at a young age, which “has revealed things like difficulty sleeping, anxiety, avoiding certain activities, and sometimes, intrusive thoughts that can persist for years or even decades.

“So it certainly is possible for frightening images in media to have long-lasting effects,” he said.

The Ottawa-based organization cites research showing that children aged between three and five years old do not understand “media cues” that are used to show that something shouldn’t be taken literally in a television program or movie. For instance, children can even be frightened of characters who may have a “weird” appearance, such as humanoids. By contrast, children aged six to eight are beginning to be able to distinguish between fantasy and reality in media, but they can still be scared by frightening images, the research found.

On the other hand, the horror-film versions of characters such as Winnie-the-Pooh and Mickey Mouse do not look identical to the Disney characters beloved by children. After Mickey entered the public domain, Disney reasserted its longstanding policy of vigorously challenging any infringement of its rights to the iconic modern versions of the characters it has created. “We will … work to safeguard against consumer confusion caused by unauthorized uses of Mickey and our other iconic characters,” the company said in a Jan. 1 statement to The Washington Post.

The next time they encounter those characters in a different context, … (even in) the original Disney movie, it’s possible that that they might feel some sort of fear response in that case, as well.

Matthew Johnson, director of education, MediaSmarts

Disney’s current version of Mickey Mouse, which remains under copyright, is easy to distinguish from the slasher persona, who is a human-looking character clad in black, with a cartoonish mouse mask based on Steamboat Willie.

For Winnie-the-Pooh, the latest horror version is a humanoid bear wearing lumberjack clothing with a scowling face and fangs, rather than the Disney version, a stuffed animal with a red T-shirt. That cuddly version of Pooh is still protected under copyright, unlike the original characters created by A.A. Milne.

But Rachel Franz, who works at the U.S. non-profit Fairplay, which advocates for children’s privacy and safety online, said it might still be difficult for children to distinguish between the classic Disney character and its horror counterpart.

She also raised concerns about the para-social relationship between a child and their favourite character, and whether seeing these characters engage in violent acts will affect that emotional bond.

“Children trust characters to be there with them and to be their kind, fun buddies. And when you have adults taking advantage of that nostalgia and … of those relationships to produce a film, it’s going to negatively impact children,” noted Franz, the education manager for Fairplay.

It can be very easy for children to stumble across the grotesque character online and share it with their peers, she noted, pointing to cases in which sexual content made its way to YouTube Kids. An example of this is “Elsagate,” a controversy that erupted in 2017 when videos showing characters such as Elsa from Disney’s Frozen and Spiderman involved in violent and/or sexual activities began to proliferate on the platform. Many of the videos have since been purged from the platform.

According to a 2020 study by Common Sense Media, children’s viewing history on YouTube Kids included content with mildly frightening themes 14 per cent of the time and they encountered very frightening themes four per cent of the time. Such content consisted mostly of gaming content that featured horror or jump scare games, such as Five Nights at Freddy’s, that included scary themes or characters. It also included videos that “foreshadowed a sense of peril, impending death, and bloody themes,” the study said.

Franz suggested that if children are troubled by the horror versions of their favourite characters, parents should explain to them that there are two versions so children do not confuse them.

So how can parents protect their children from exposure to scary versions of characters such as Winnie and Mickey?

Johnson suggested that parents explain to their children about the safe context behind a frightening image, and remind them that it’s not real.

Otherwise, he explained, if they are accidentally exposed to this content, “the next time they encounter those characters in a different context … (even in) the original Disney movie, it’s possible that that they might feel some sort of fear response in that case, as well.”

Parents can also create a child-friendly profile that filters the type of content their children watch and encourage them to tell about any mature content.

Amy Jordan, professor and chair of Rutgers University’s Journalism and Media Studies Department, said parents need to tailor their approach to the sensitivity of their child.

“It really depends on the child, and parents really need to understand their child’s limits and their child’s reactions,” she said.

But protecting children from online harm is getting more and more difficult, she noted.

“I don’t ever want to blame parents (and) to say (they) are more relaxed than they were before, because they aren’t. It’s just that the media landscape has changed in a way that has made it more challenging for parents,” she said.

In a 2022 survey conducted by MediaSmarts, more than 20 per cent of youth reported receiving discomforting or harmful content online. Additionally, 78 per cent of youth responded that their parents or guardians are worried that they could get hurt online.

Franz argued that streaming and social media platforms should be held accountable when it comes to protecting children from mature or harmful online content and that they should be more proactive.

The precautions available to parents are not foolproof, Franz said. “That’s why we point back to those companies, because they actually can control those things in a lot of ways.”

The federal government’s proposed Online Harms Act would force social media companies to take stronger measures to reduce children’s exposure to harmful content and to make some types of content inaccessible to minors. Tabled in February, Bill C-63 would also create a new Digital Safety Commission, an ombudsperson and a Digital Safety Office.

The bill comes on the heels of similar legislation in a range of G7 countries, including the U.K, Australia and some European countries.

But it could be years before any concrete measures are in place in Canada; Bill C-63’s current status is only at second reading in the House of Commons. If it eventually receives royal assent, it will take more time to establish the regulations that would guide implementation of the new law.

In the meantime, will the images of iconic characters Winnie-the-Pooh and Mickey Mouse be forever tarnished by their horror-movie counterparts?

Garlen said she isn’t worried.

“I don’t think that it will really … have sort of a lingering long-term effect on the way people think about Winnie-the-Pooh, Bambi or Mickey Mouse. I think that those reputations are pretty stable and will still hold.”