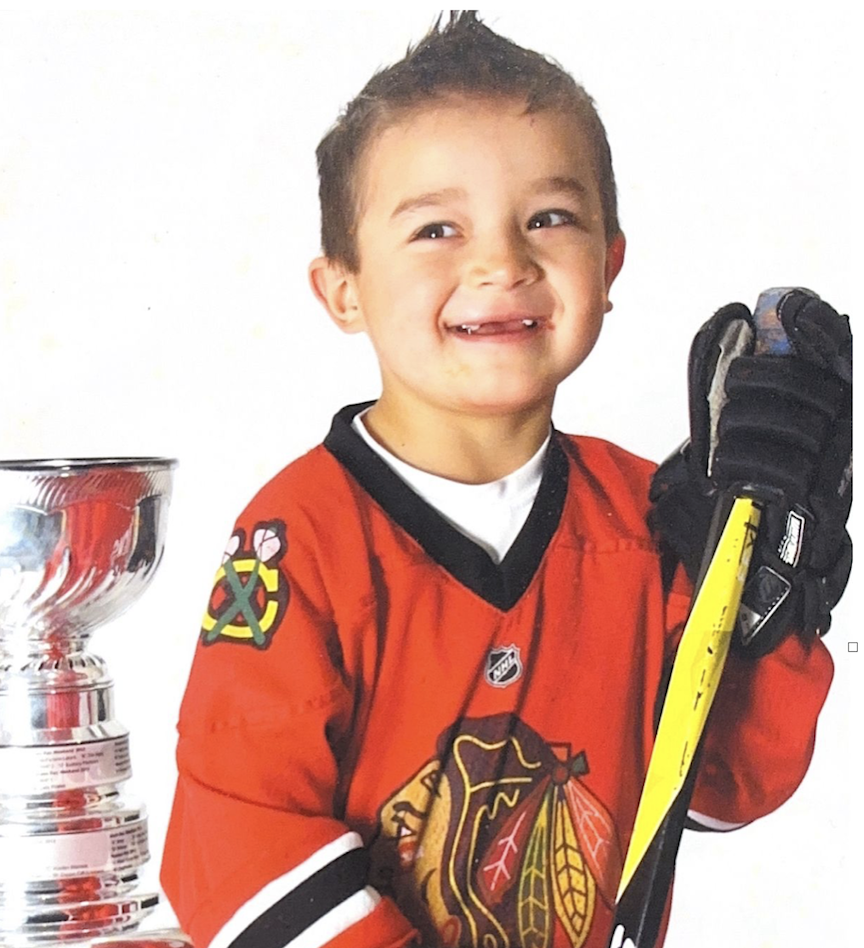

When Kohyn Eshkawkogan of the Ottawa 67’s scored his first Ontario Hockey League goal last October at age 15, it marked a new step on the long path that previous generations have paved for hockey’s accessibility in Indigenous communities.

Hailing from M’Chigeeng First Nation on Manitoulin Island, a two-hour drive south of Sudbury, Eshkawkogan is the first member of his family to reach such a high level of competitive hockey.

His accomplishment reflects a broader shift, as more and more Indigenous players are breaking through at elite levels. It is the result of years of advocacy, increased support and growing visibility for Indigenous athletes in hockey.

Hockey Canada says Indigenous hockey registration is at its highest point ever, with more than 27,000 players identifying as Indigenous. That’s five per cent of overall registration. The governing body says it believes participation will grow almost four per cent a year thanks to these events specifically designed to attract Indigenous players as well as organizations making the sport more accessible and the improving skill level of Indigenous players.

“I think they’re now having better access to resources to get better at the game,” said Dustin Peltier, general manager of Eshkawkogan’s Team Ontario, which won the annual National Aboriginal Hockey Championship (NAHC) in 2024. “They’ve had more trailblazers than there used to be so they now see what it takes to get there, the work they have to put in and there’s more people, like myself, out there to offer what they can.”

Events like the NAHC, which drew more than 1,000 fans a game last year, have become more accessible for Indigenous players. Eshkawkogan’s father, Kevin, credits the growth to previous generations of Indigenous hockey players, such as himself, leading the way and the resilience players like his son showed on their paths through the sport.

The NAHC held its first national tournament in 2002 and has since produced six NHL players and three professional women players. Its U18 division, in particular, has exploded in participation.

“These players are coming from elite hockey academies or they’re playing junior hockey or AAA hockey,” said Brock Freeman of Indigenous Sport, Physical Activity & Recreation Council, BC’s Indigenous sports governing body. “So they have the opportunity to represent their home province or territory and it is very competitive.”

Peltier said more than 140 Indigenous kids showed up to tryouts last year in North York, a sharp increase from the 25 that attended in 2021, his first year with the program.

Many organizations, including the NAHC organizers, provide funds, coaches, ice time, equipment and other resources that may be inaccessible in some communities.

“In smaller communities, you may not have access to the right coaches or the right programs, the right equipment,” said Freeman, referring to making hockey more accessible through providing funds and staff to those communities. “So when we come in to partner with different communities, we try to eliminate some of those challenges.”

Along with awareness of the championship, organizers also credit the rising skill level of participating players.

“The native brand of hockey” in the NAHC is as tough as any other league Peltier knows, he said, especially for a U18 tournament. Most, if not all, players finish their checks, skate hard and never give any room to opposing players.

“The quality of competition has certainly gone up,” added Peltier, noting a rise in the number of participants that are making major junior teams or the NCAA in the U.S.

(Indigenous players have now) had had more trailblazers than there used to be so they now see what it takes to get there, the work they have to put in and there’s more people, like myself, out there to offer what they can.

Dustin Peltier, general manager of Eshkawkogan’s Team Ontario

Jocelyn Laroque, an Indigenous player in the Professional Women’s Hockey League, described how the tournament has changed since she played on Team Manitoba 20 years ago.

Laroque, a three-time Olympic medalist and a defender for the PWHL’s Ottawa Charge, said that “pretty much everyone that went to the tryout made the team” when she played in the early years.

“Just to see how many teams there were and how big of a tournament (it’s become), it’s great to see,” she said. “Especially on the women’s side specifically it’s grown a lot. That representation is important for young Indigenous hockey players to see those tournaments that they can strive for.”

Laroque, 36, was part of the first generation to take part in the NAHC and other hockey events dedicated to the Indigenous community.

Kevin Eshkawkogan, 47, missed that window. He was the only Indigenous player on the teams he played on growing up. Unlike a lot of other members of his community, he got to play, but he says his path through the sport was harder than his son’s.

“Late at night after partying with whoever, I’d be in those areas where they’d beat you down and throw you in the river and you’d die,” said the elder Eshkawkogan. “If it wasn’t for hockey and my teammates, who were all non-Indigenous, keeping an eye out for me, I may not even be alive.”

With his son now on an OHL team, he says he tries to attend every home game and bring other members of the community to support the 67’s and their Indigenous player.

This was seen at a 67’s game last October in Sudbury. Despite the younger Eshkawkogan missing the game because he was representing Canada at the U17 World Challenge tournament, many of the fans wore 67’s gear instead of home-team merch.

His father, however, says it didn’t matter that he wasn’t there, people wanted to show their support. “Part of our culture is that we support each-other,” said the father. “There must’ve been 500 people there [for] Kohyn. It was like a home game.”

Eshkawkogan also has five 67’s season tickets that he often shares with other Indigenous people wishing to see a member of their community play at such a high level.

His son is far from being the only Indigenous player to be making strides towards the NHL draft. Along with the handful of players already in the league, the projected first overall pick in the upcoming draft, Gavin McKenna, is from Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation near Whitehorse.

With the rising representation from players in the big leagues, the NHL and other major hockey organizations have started holding Indigenous Culture Celebration Nights, including the Toronto Maple Leafs and the Ottawa Senators. Both, in part, have been organized by Kevin Eshkawkogan, who is also the president and CEO of Indigenous Tourism Ontario.

He also said the organization pioneered the way land acknowledgements and other ceremonies are held across the province.

According to the father-son duo, representing the Indigenous community is just as important as Kohyn’s on-ice performance.

Traditional Ojibwe community values were a huge part of the Eshkawkogan household when the young defenceman was growing up. The elder Eshkawkogan says they mostly centre around helping those in need, perseverance and staying close to one’s family.

“My dad taught me not to be shy about who you are and represent the community,” said Kohyn Eshkawkogan, who is already on the radar of many NHL scouts.