Every year, around 250,000 birds are killed by crashing into glass in Ottawa — typically the windows of private homes and high-rise buildings.

For Safe Wings, a non-profit group working to reduce the number of avian casualties through research and advocacy, this carnage is preventable.

That’s why Safe Wings Ottawa recently took its message about preventing these deadly collisions to the Canadian Museum of Nature.

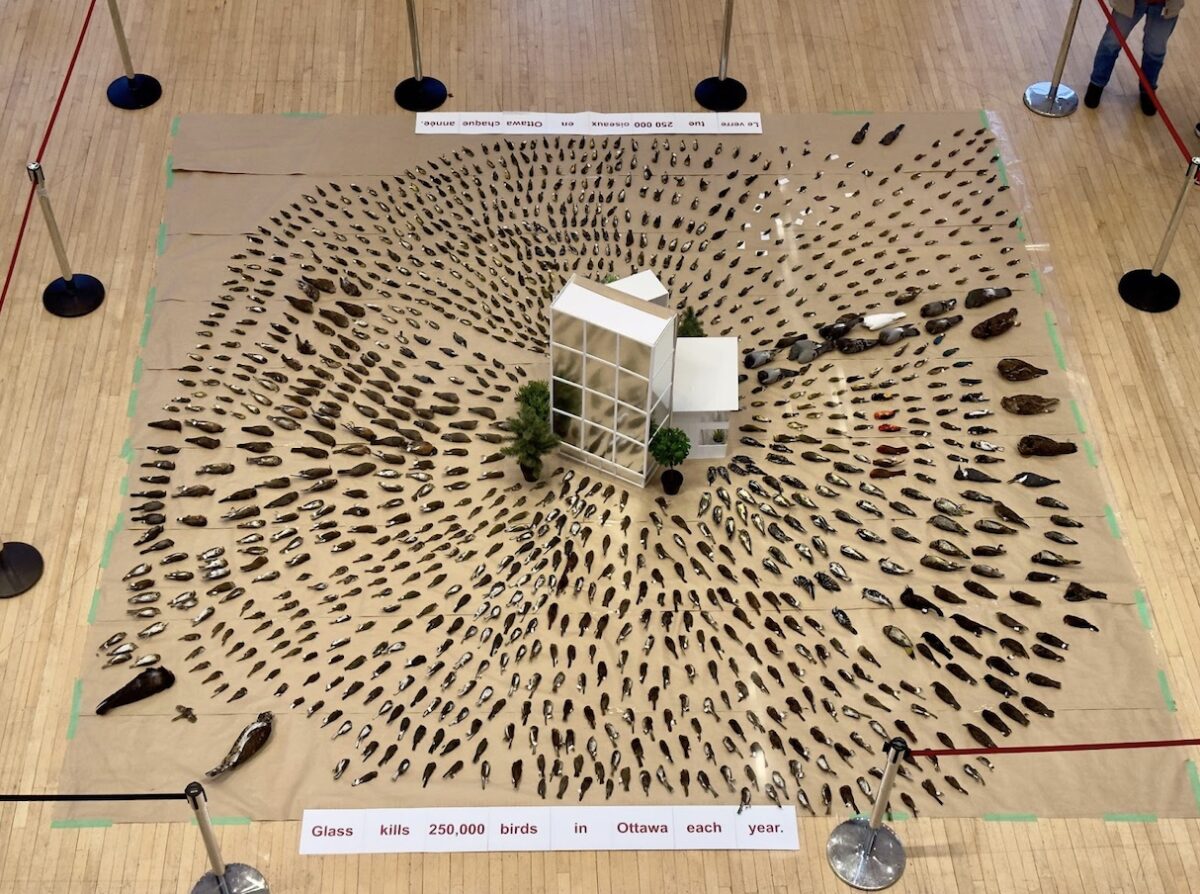

In the museum’s Hatch Salon, the group displayed hundreds of birds that have died by colliding with glass in the city. The dead birds — only a small portion of birds that die every year in window strikes — were placed on the floor of the salon in concentric circles to underscore how extensive the problem is.

Jenette Niwa, a volunteer with Safe Wings, said the group organized the display to spread awareness of a big conservation challenge with simple solutions.

Most people think, ‘Oh, a bird hit my window, it hardly ever happens.’ But if you figure if we have a quarter of a million houses in Ottawa, and every house had one bird hit their window and die — right there, that’s a quarter of a million.

Jenette Niwa, volunteer, Safe Wings Ottawa

“Most people think, ‘Oh, a bird hit my window, it hardly ever happens.’ But if you figure if we have a quarter of a million houses in Ottawa, and every house had one bird hit their window and die — right there, that’s a quarter of a million,” she said.

“Most people don’t realize that their houses are culprits.”

Gregory Rand, the museum’s assistant collections manager, said he believes the display sensitizes people to the issue.

“A lot of bird populations in North America are in decline,” he said. “Even over here (in the exhibit), I can point out a number of species at risk that have just collided with windows randomly. And this is only a fraction of the birds that are dying.”

Reports estimate that about a billion birds are killed worldwide by glass collisions every year.

The display certainly had an impact judging by the shocked expressions and audible gasps by visitors, including Shannon Hall.

“It’s really sad,” she said. “It just becomes more real.”

Safe Wings does a lot of work to bring this kind of awareness to the public. The volunteers monitor certain buildings, take in injured birds and keep track of bird collisions with windows.

Tracy Chapman, lead coordinator of Safe Wings’ phone volunteers, said calls include reporting window-bird collisions, car-bird collisions, or the discovery of baby birds. Safe Wings typically advises callers about what to do with the birds, whether they need to be collected and how to collect them.

Chapman grew up volunteering for the Wild Bird Care Centre in west end Ottawa, but stopped after moving away from the city.

She said seeing two birds collide into her window pushed her to find Safe Wings and start working with the advocacy group.

“The first one died in my hands,” she said. “I knew I had to do something about it, but I wasn’t sure what it was.”

Chapman did not know about Safe Wings until the second bird hit her window. She collected it and called the Wild Bird Care Centre, which directed her to Safe Wings. She said she immediately wanted to get involved.

“I think it’s important to get us in front of the public, to get the public thinking about the reasons why birds collide and what they can do to avoid it,” she said.

Birds crash into glass because they view windows as open pathways that they can fly through. They also may think reflected skies and trees are real. This leads them to crash into the glass at full speed, causing serious injuries or death.

Bird collisions are most common during the spring and fall migrations when larger numbers of birds are passing through Ottawa.

The first one died in my hands. I knew I had to do something about it, but I wasn’t sure what it was.

Tracy Chapman, volunteer coordinator, Safe Wings Ottawa

Niwa said windows in residential areas are the deadliest in Ottawa simply because there are so many.

But there are many ways residents can make their windows bird-friendly, she said. The most effective solution is a Canadian product called Feather Friendly, a vinyl marker of dots that is applied to the exterior of the window.

Residents can alternatively create their own dot patterns using oil-based markers. Designs and decals are an option, as long as there are no gaps larger than three centimetres, said Niwa.

Although homes account for a large portion of the deaths, other city buildings, such as skyscrapers, are also a significant threat because they are made of so much glass.

Safe Wings monitors buildings around the city to determine which ones pose the biggest risk to birds. Tracking information on bird collisions, such as what species are crashing, on what side of the building and how many times it happens, does encourage these building managers to become more bird-friendly, said Niwa.

She recalls a specific instance when she reported a high number of collisions in a portico to a landlord. She wasn’t sure what would come of it until she returned to the building a few weeks later.

“I showed up there one day, (…) and they had Feather Friendly-treated the entire glass portico,” she said. “And I have not found a single bird since then.”

Those who find dead or injured birds should contact Safe Wings after placing them in an unwaxed paper bag or a shoe box if it’s a larger bird.

Niwa said that though window strikes are a huge issue, it often goes unnoticed given how small birds are and how easy it is to miss them. She said dead or injured birds often get scavenged by other animals before they are discovered.