When Doug Ford stopped by the Château Laurier on a recent trip to Ottawa, he didn’t take the bus. He didn’t climb Canada’s longest escalator from the depths of Rideau Station, nor did he bike down either of the pathways that flank the canal.

He arrived in a black SUV to a discrete entrance, far from the peloton that had gathered to protest the province’s new bike lane restrictions — ones that Ford says will alleviate congestion and cyclists say will put them at risk.

At issue is the provincial government’s Bill 212, the Reducing Gridlock, Saving You Time Act. The legislation would forbid the construction of new bike lanes in Ontario if they required the removal of car lanes, unless specifically approved by the province. This could obstruct a significant portion of the City of Ottawa’s current Active Transportation Plan, which calls for the construction of new cycling infrastructure across the city. The province is even targeting existing cycle tracks and has singled out the lanes on O’Connor Street, running from the Glebe to downtown.

“Doug Ford doesn’t know Ottawa,” said Alex Sereda, a cyclist from Vanier, when asked about the proposed legislation. “According to established processes, the councillors that we vote for in our wards, that live and work in these streets, they should be the ones making decisions.”

Mayor Mark Sutcliffe hasn’t weighed in much on the proposed ban, simply saying that the city will comply with the new regulations.

William van Geest, interim executive director at Ecology Ottawa, said he’s not surprised.

“He has a terrible track record on biking infrastructure. It was so disappointing to see him not only campaign against biking infrastructure, but also to make it a wedge issue,” said van Geest, referring to the 2022 municipal election.

Most of the protestors at the Nov. 5 rally arrived in fitting fashion, riding bikes of every sort imaginable. Some had light frames and skinny tires for road racing, some had luggage racks for important cargo (be it a canoe or a baby.) There was even a rickshaw, equipped with a push operated air horn, which blared in support as the group chanted. While the mood was positive, the message was grim — that the proposed law would endanger cyclists by forcing them share more roads with cars.

Ottawa’s Existing Network

As far as recreational cycling is concerned, Ottawa rates quite well. There are dozens of bike paths that weave through the Greenbelt. Two long trails, that sit on former railbeds, permit the enthusiastic cyclist to go as far west as Carleton Place and as far east as Rigaud, Que. Those looking to push themselves can tackle the Gatineau Hills across the river. The NCC even closes some of its major parkways in the summer to allow cyclists to ride free of car traffic.

But the problem isn’t finding a place to ride on the weekends, cyclists say. It’s finding a safe way to get around town. For people without cars, biking can be a cost effective and environmentally friendly way to get to the office or the store.

“I ride on bike lanes and it’s great, but all of a sudden they disappear and you’re thrown in with the cars,” said Stephen Johns, a cyclist from Old Ottawa East. “I think that’s probably why a lot of people aren’t moving towards cycling. It’s an incomplete system.”

Infrastructure improvements are supposed to be on the way. The city’s Transportation Master Plan, the long-term framework for the city’s transportation system, outlines dozens of new cycling projects, from new lanes to traffic lights for bikes. The plan is part of the city’s goal of reducing car trips, as well as reducing its carbon emissions, of which almost half come from transportation. But if Bill 212 becomes law, progress on new bike lanes is expected to stagnate.

Congestion

The purpose of the proposed legislation is, ostensibly, to relieve congestion for automobiles. It’s no secret that Ottawa’s roads are often jam packed, but the stats suggest bike lanes aren’t to blame.

While the city added 260 km of bike lanes from 2013-2022, very little of the new infrastructure was made up of segregated bike lanes — ones with physical barriers between car and bike traffic. That means most of the new infrastructure is made up of either pathways or painted road shoulders, neither of which tend to interfere with car traffic.

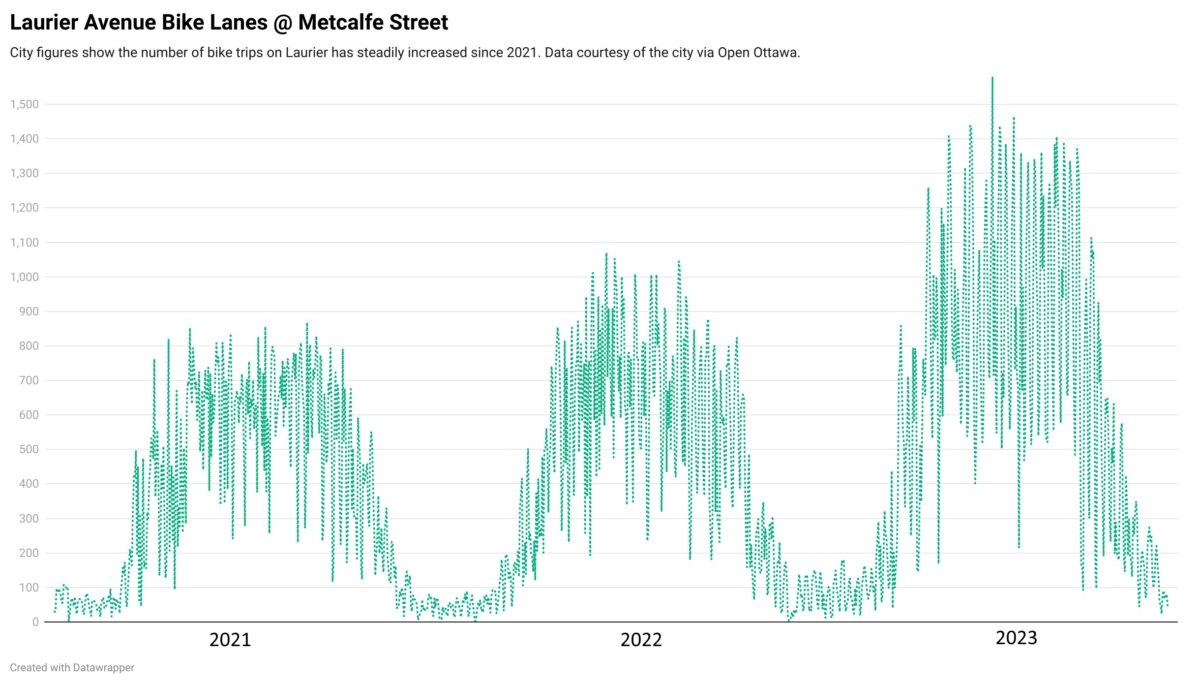

And though these segregated lanes may be sparse, more and more cyclists are riding them every day. Among the busiest are the lanes on Laurier Avenue.

This chart shows a steady increase in ridership on the Laurier Avenue bike lanes since 2021. And as more federal workers return to the office, usage could start to climb back to pre-pandemic levels.

What’s Next?

If the province decides to rip out the existing bike lanes on Laurier Avenue and O’Connor Street, which stretch a combined roughly four kilometres, it would likely cost millions. A City of Toronto report estimates removing three of its major bike lanes would cost $48 million.

For those opposed to the planned ban, activists suggest reaching out to city councillors. “There are a lot of folks in the rural and suburban wards that haven’t said anything. It’s up to us to get them to say something,” said Sam Hersh of Horizon Ottawa.

An even greater opportunity to raise the issue is likely coming in the spring, as there is wide speculation that Ford will call for an early election.