Many drivers who have traveled through downtown Ottawa can attest that finding parking isn’t easy. Whether it’s a social trip to a restaurant, or to attend a medical appointment, finding on-street spots can mean parking a few blocks away. While a trivial inconvenience to some, others must think about opening their trunks to retrieve their mobility devices or the difficult paths they might have to navigate to reach the safety of the cuts to the sidewalk.

“I have to walk in traffic to a point where I can get up onto the sidewalk,” Cathy Malcolm-Edwards said when recounting what on-street parking is like for her, as an accessible parking permit holder and someone who uses mobility devices.

A new pilot project is in early planning stages for the City of Ottawa to designate on-street parking spots exclusively to permit holders with limited mobility as competing demands for road space slowly erode current options for accessible parking in the busiest downtown areas.

The availability of parking spaces has declined for people with disabilities or limited mobility as the city balances accommodating cycling lanes, construction projects, electric scooter parking, and other competing infrastructural needs, said Lucille Berlinguette-Saumure, a recently retired accessibility program manager with the city.

Addressing the issue of disappearing accessible parking zones “is something that the city’s accessibility advisory committee asked for 10 years ago,” said Berlinguette-Saumure. Downtown no-parking zones, which are available to be used as accessible spots for those with permits, are being repurposed for other transportation and economic needs, she added.

Jerry Fiori, past-chair of the Ottawa Disability Coalition, doesn’t see no-parking zones as a significant factor in solving the accessible-parking problem.

“No-parking zones only do so much,” said Fiori, whose organization consults with the city.

ParaTranspo drop-off is deterred by shoulder spaces that have been allocated towards bike lanes unless there are designated spaces to stop, said Fiori. Also, on-street accessibility involves factors beyond parking, and no-parking zones themselves only account for a small portion of available spaces.

These limitations have also become reality for a woman whose accessible parking in front of her apartment building was displaced by a construction project, forcing her to find street parking. Most days, she has found herself parking three blocks away, recounted Thony Jean-Baptiste, program manager at Able2, a not-for-profit organization that supports people with disabilities.

Right now, she can park far away but, in the winter, if she falls on her walk home, “it will be the beginning of the end,” Jean-Baptiste said of the woman, who sought help from his organization. Even with an accessible parking permit, there are limited areas to find nearby parking which becomes not only an issue of access but of safety. Obstacles related to street parking and “access issues for people with disabilities, are also safety issues,” said Fiori.

Currently, all on-street parking is considered accessible. People with accessibility permits can park on any street with parking signage free of charge for up to four consecutive hours, including areas at the ends of streets that are typically marked as no-parking zones. Rather than having labelled spots, the city’s bylaw on accessibility bike lanes and other land use changes downtown using up no-parking zones, spots for permit holders are declining, said Berlinguette-Saumure.

And yet, to some, Ottawa is not inadequately accessible. “The city, in my view, has some pretty good permit rules,” said Dean Mellway, Carleton University expert in physical accessibility who uses an accessible parking permit. “I’m not opposed but I don’t think it’s a priority,” Mellway said about his initial thoughts on the proposed pilot project. “Five spots do not sound like much.”

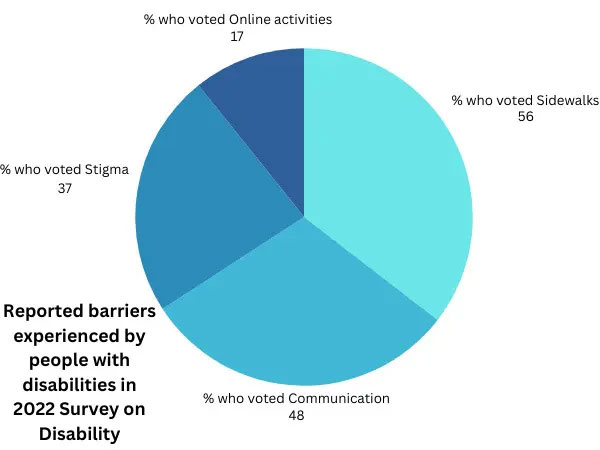

In 2022, 27 per cent of Canadians over the age of 15 had one or more disabilities that limited their daily activity, of whom 56 per cent reported experiencing barriers regarding sidewalks, an issue considered to be directly related to on-street parking.

The city is now working to amend the traffic and parking bylaw to place five properly sized and clearly labelled accessible parking spots along sidewalks, much like those found in parking lots. While spots are not yet determined, areas near pharmacies, medical centres and busy main streets have been of particular concern for persons with disabilities on the advisory committee, said Berlinguette-Saumure.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if they even ended up in the ByWard Market,” she said.

Ottawa is embarking on its pilot project at a time when several other cities have already implemented similar initiatives. Ontario is the first province to enact specific legislation establishing set targets and a time frame of 2025 for improving overall accessibility. Cities such as Kingston, Toronto, and Brockville, have already implemented designated on-street parking with signage and road paint.

Kingston began designating accessible on-street parking spots in the 1980s. Kingston’s 75 designated spaces can be found throughout its “downtown district, hospital and university districts, and in the vicinity of some churches and residential areas,” Greg McLean Kingston’s transportation services program manager, said in an email. However, Kingston permit holders are not exempt from parking fees like Ottawa holders are.

I’m not opposed but I don’t think it’s a priority.

-Dean Mellway, physical accessibility expert

Accessibility is a nuanced and often overlooked topic, said accessibility and disability expert Malcolm-Edwards. It can all-too-often be considered within limiting parameters that are defined by “assumptions and stigma that go along with having a disability.” If the city implements five accessible spaces in front of medical centers, while that is good for some people, it’s assuming that most people with disabilities have medical conditions when this is not always the case, said Malcolm-Edwards.

If Ottawa’s bylaw is amended, designated on-street parking spots will be implemented in 2025 to supplement existing availability, including areas at the ends of streets that are typically marked as no-parking zones. This would align with the city’s 2023-2026 term of council priorities, to create a city that has more reliable mobility options.