In 1994, a movement of mostly rural Indigenous people, known as the Zapatistas engaged in an armed uprising against the Mexican government which began as the first North American Free Trade Agreement was signed.

The Zapatistas announced a series of demands, including land reform, economic and social justice and others.

The movement continues to this day as a force in the Mexican state of Chiapas. In the form of photographs, many important moments in Zapatista history have now been put on display at the Mexican embassy in Ottawa.

The Jungle’s Reasons opened Jan. 21 at the embassy on O’Connor Street.

The exhibition is a partnership between the Mexican Embassy and Bats’i Lab, a Mexican collective that focuses on using photography to promote social justice causes.

The exhibition’s curator is Ali Rodriguez, a Mexican-Canadian who graduated from Concordia’s photography program. Born in Mexico but raised in Ontario, she moved back to Mexico following graduation to start projects such as The Jungle’s Reasons.

“Having these exhibitions in a government building is an effort to recognize the efforts by the Indigenous people to fit in with the Mexican narrative,” said Rodriguez, during a call from Mexico.

“When we talk about the history of Mexico, the Zapatista movement has formed the history of this place. Even if they view themselves as a separate entity, when we see the whole context globally, we have to consider their history in ours.”

The Zapatista uprising began in response to the North American Free Trade Agreement, which they believed would make the country’s many Indigenous peoples even worse off. The Zapatistas, whose movement is widely studied, eventually transitioned into a political group, leading demonstrations and governing territory in Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico. Their resistance served as an inspiration for movements worldwide, including Occupy Wall Street.

Many representatives of the Mexican government now believe that the treatment of Indigenous people and the response to these uprisings marks a dark chapter in the country’s history.

“In Mexico, this is very important because it was the first time that the native people protested in a large mobilization to claim against the federal army, who was persecuting the Indigenous communities in the Altos of Chiapas,” said Ingrid Berlanga, the Mexican Embassy’s head of Cultural Affairs and Tourism.

“We think that it’s important to share part of our history, even if it is a little hurtful for us, for the State of Mexico.”

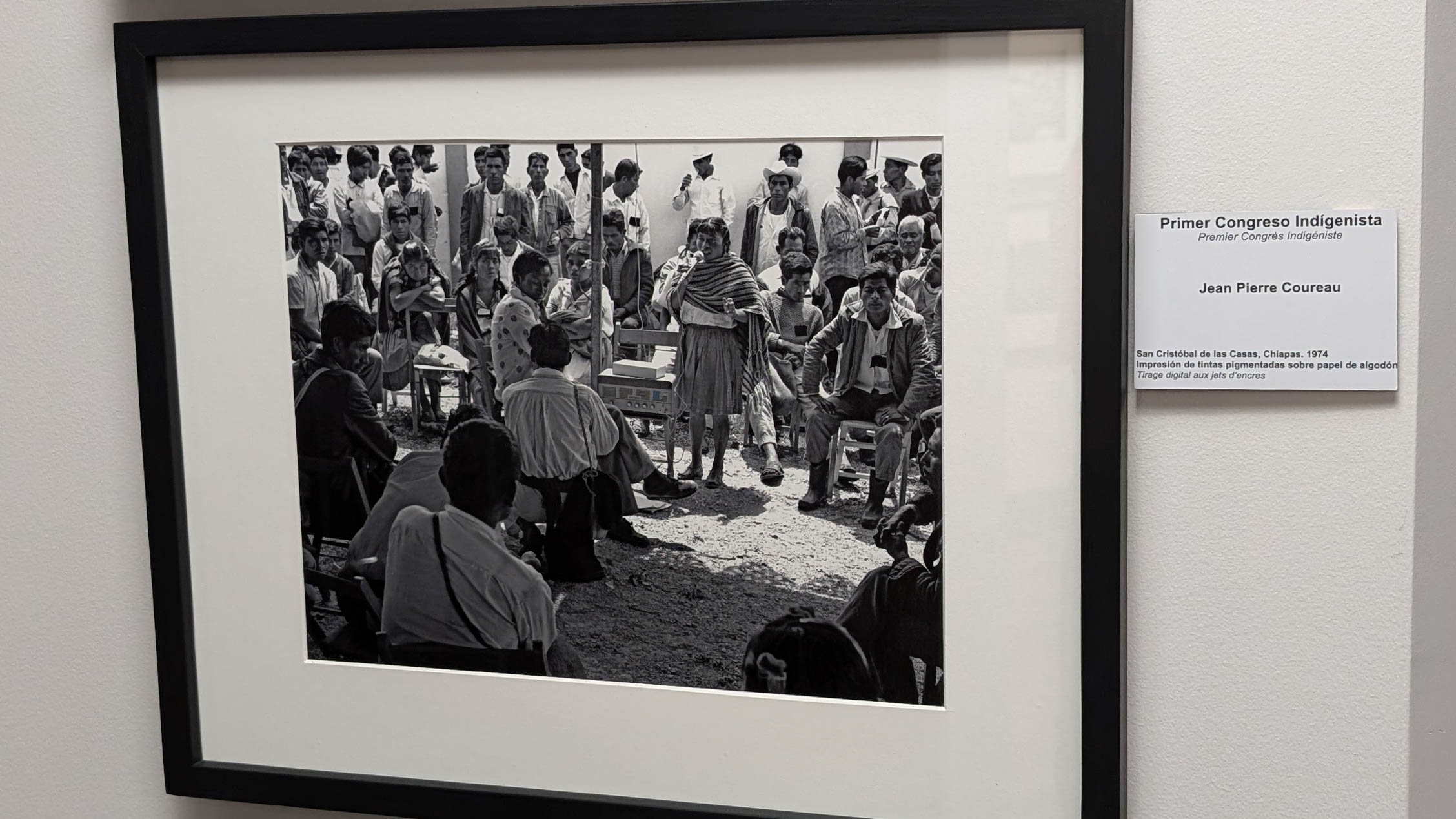

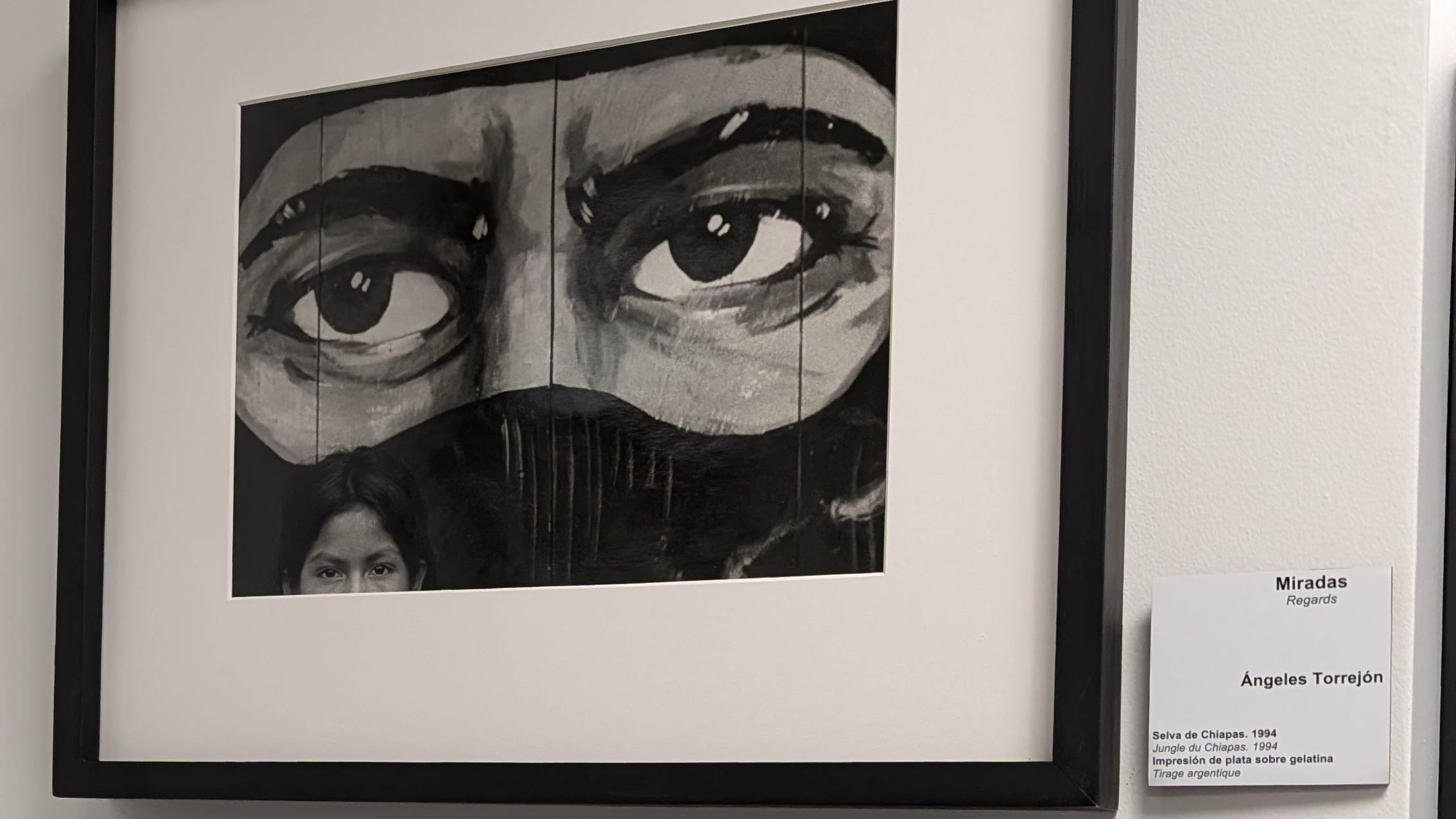

While the Zapatista movement gained prominence in the 1990s, the gallery’s photos go back before the events of 1994. The gallery is split into four sections, each representing a theme and corresponding time frame in the movement’s history.

Only seven of the images showcase the uprising, as Bats’i Lab wanted to showcase the movement beyond its military wing.

Here are some images from the exhibition courtesy of the Mexican Embassy:

Opening night drew a crowd of nearly 100. Greeting the visitors was Mexico’s Ambassador to Canada, Carlos Joaquín González.

“This story resonates deeply in Canada, a country that has also faced historical and contemporary changes in its relationship with Indigenous peoples,” González said during his speech.

“Just as the Zapatista movement demanded recognition and autonomy, Canada has taken significant steps towards reconciliation.”

Solidarity between Indigenous groups worldwide is a major theme that Rodriguez, Bats’i Lab and the Mexican Embassy wanted to emphasize with the exhibition.

“What the Zapatista movement did, which is so important, is that it put Indigenous resilience to the forefront of media,” said Rodriguez.

“And this is where it connects with other Indigenous groups globally. We’re talking about the consequences of 500 years of colonialism, we’re talking about generational trauma that has been passing itself on for generations and generations.”

Mickey Akarasewi, who attended the opening, says that the plight of the Zapatistas hits close to home.

“I see the importance of people trying to seek their freedom,” Akarasewi said. “I’m from Thailand, and we have the same problem, but the way that they protest is really interesting.”

It’s estimated that 10 per cent of people living in Thailand are of Indigenous heritage. According to the Bangkok Post, evictions of people inhabiting traditional Indigenous lands are still common in the country.

Federico Arellano, a Mexican entrepreneur who came to Ottawa as an international student years ago, says that events, such as The Jungle’s Reasons, allow him to share his knowledge of his country’s history.

“Sometimes, the way Mexican culture handles Indigenous communities is a bit hard to understand,” Arellano said.

“I’ve been asked all sorts of questions regarding what the situation is like and if it’s improving, and if they [Zapatistas] were actually a violent group.”

Arellano says that when asked about the state of Indigenous people in Mexico, he says it’s complicated.

“I do think for sure that they are having way more visibility and that’s a nice way to start,” Arellano said. “But I think that the situation of Indigenous people only reflects how different and how separate from each other the higher social classes in Mexico are to the lower ones.”

With the recent immigration crackdown in the United States, Rodriguez says that now is as important of a time as ever to showcase the Mexican experience.

“We’re seeing a lot of news about deportations,” Rodriguez said. “This is all part of the same narrative, it’s all part of this systemically complicated oppression that happens to people who are from these countries. People migrate to North America to find better living situations, and then years later get deported.”

Rodriguez says that she wants people to come out to the gallery to learn the roles that people from Latin America play in the global community.

“This is a really good example of listening to someone else’s story,” Rodriguez said of the gallery. “Even though (the movement) is separated from us, it does touch us in very personal ways, in ways that affect us socially, globally and personally.”

The gallery remains open to the public Monday to Friday at the Mexican Embassy on 45 O’Connor St. until March 21.