This story first appeared in Capital News Online on April 11, 2018.

Native bees are vitally important for pollinating native flowers and crops. But little is known overall about their distribution and populations levels in Canada. While beekeepers and honey bee colonies are increasing in Canada, some researchers fear that putting a hive in your backyard could negatively impact wild bees.

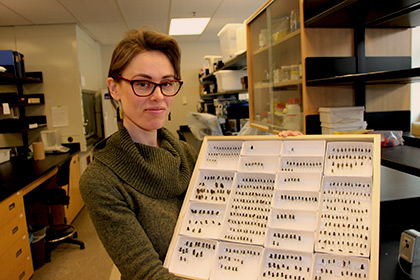

“What kind of amazes me is how many things we don’t know about wild bees. In some cases, we don’t even know what flowers they prefer to visit,” says Jessica Forrest, a native bee researcher at the University of Ottawa. One thing is known: Some native bees are in steep decline. But nobody knows why.

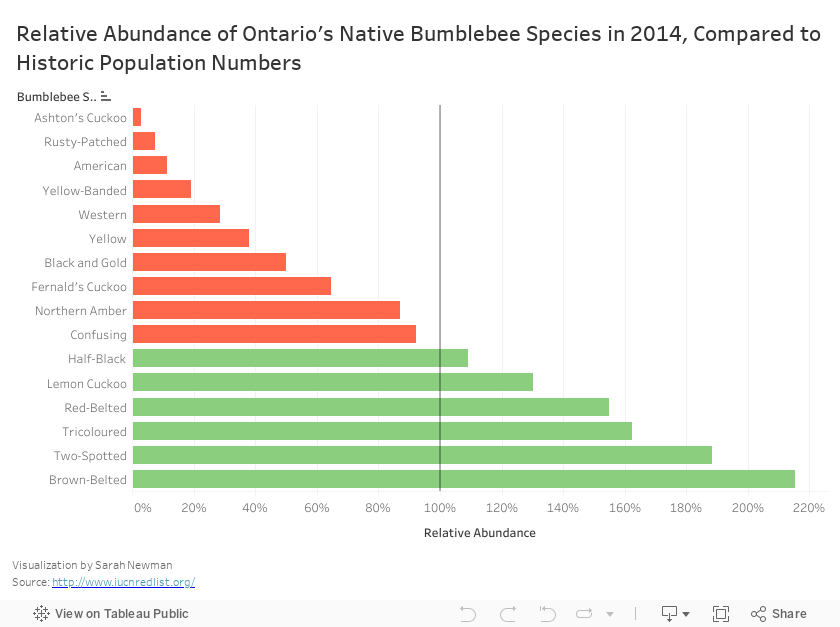

Take the rusty patched bumble bee, which is found in eastern North America and was one of the most common bumble bees in Ontario in 1970. In the mid-1990’s, scientists noticed their populations swiftly declining. Now endangered, the bee has not been spotted in Canada since 2009. It is one of six threatened species of bumble bees in Canada.

[The following chart shows the status of 16 Bumblebee species. Those in red are in decline. Those in green are experiencing growth.]

Bumble bees are the most researched bee species in Canada. However, Sheila Colla, a native bee researcher at York University, says we have almost no idea how other non-bumble bees are doing. There are more than 800 species of native bees in Canada, of which 40 are bumble bees. There are more than 400 native bees in Ontario alone.

The cause for their declines is not well understood and could include pesticides, diseases, habitat loss, and climate change. Some studies suggest that competition and diseases from honey bees could be contributing factors.

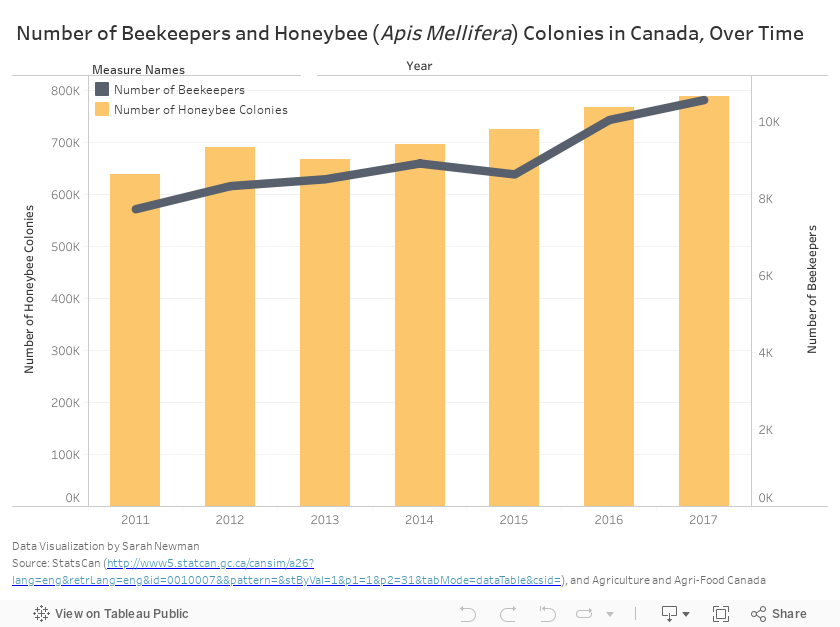

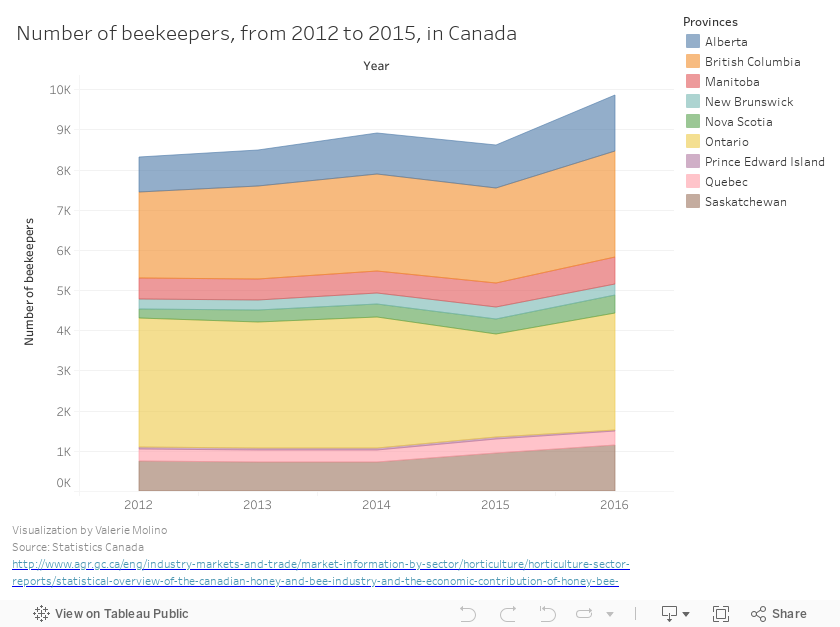

Honey bees were introduced to North America in the early 17th century. Most have been domesticated for honey production and crop pollination. And beekeeping is on the rise in Canada, with 8,777 beekeepers nation-wide in 2014, up from 4,703 in 2010. Ontario has the largest number of any province, with just over 3,200 beekeepers. Anyone who owns or is in possession of honey bees must register annually with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture. However, the profession isn’t as prolific as it was during World War II, when Canada was home to more than 43,000 beekeepers in Canada. Beeswax was a key component in making ammunition belts for the war effort. Also, since sugar was rationed, some people turned to honey as a substitute.

Some say the rise in beekeepers could be putting native species at risk.

“People think the only good thing you can do to save bees is to put a honey bee hive in your backyard and that’s the worst thing to do,” says Beatrice Olivastri, CEO of Friends of the Earth Ottawa. The honey bees compete with native bees for flowers and pollen. They may also spread disease.

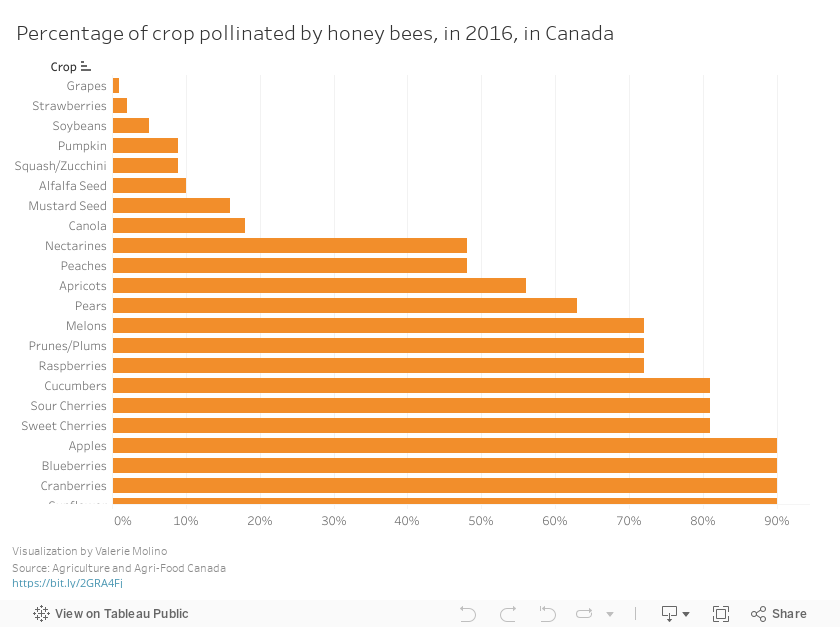

“Beekeepers are like farmers. They are managing livestock, in a sense, honey bees,” says Olivastri. Although honey bees are important for the pollination of a range of crops, they cannot replace native bees.

Native bees have co-evolved with native flowers and have adapted to Canada’s cold climate. Native bees not only pollinate native flowers, but they are much more effective at pollinating blueberries and tomatoes than honey bees, says Forrest. She refers to native bees as an “insurance policy.”

“If honey bees decline and we don’t destroy natural habitat, there are some native bees that can take up the slack.”

Without humans, honey bees wouldn’t survive, says Forrest. Beekeepers feed honey bees corn syrup in the winter, wrap them in blankets to stay warm, and spray them for pests. Native bees suffer from all the same factors as honey bees, but they don’t receive any help, she says.

Colony Collapse Disorder is a phenomenon that occurs when the majority of worker bees in a colony disappear and leave behind the queen. In 2007, the Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists (CAPA), said in their annual report that 30 to 90 per cent of their honey bee colonies in the U.S. were too weak to pollinate crops. Overall, honey bee decline in the U.S was estimated to be 40 per cent.

Every winter it’s normal that a percentage of honey bee hives is lost. According to CAPA, during the 2016/2017 winter, more than 25 per cent of hives were killed nationally. Hive loss in 2015/2016 was almost 17 per cent. Causes of colony loss include unhealthy queens, cold weather, disease, pesticides, and weak colonies in the fall. Generally, winter hive loss is greater today then 50 years ago, by 10 per cent.

Gees Bees Honey Company is a local company that rent hives to people in Ottawa. The hives are set up in yards and even on roofs. Customers include the CBC and Brookstreet Hotel. The honey company manages 200 hives across the city.

Marianne Gee, one of the owners of Gees Bees, says she questions the science behind urban beekeeping causing native bee decline. She says that the real threats to honey bees are monocultural farming, global spread of parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers due to habitat loss.

“We’ve paved paradise,” says Gee in a Tedx talk given in Kanata in March.

Neonicotinoids have received some of the blame for declining populations of honey bees and native bees. They are a nicotine-based pesticide that’s used by farmers on field crops and fruit orchards. The pesticides are still used in Canada.

Sheila Colla says neonicotinoids may only be causing part of the decline of rusty patched bumble bee.

“It’s impossible to say we know what caused it’s decline. However, only something like an introduced disease or climate change could work that quickly over such a huge landscape.” Colla also studies bees in the boreal forest, where there is little neonicotinoids usage. She says native bees are declining there as well.

Climate change could also be a factor for native bee decline. Forrest has found that while temperature increases help bee populations, parasites associated with bees also increase, which are bad for bees. It’s a difficult equilibrium.

“We’re still trying to figure out the balance,” says Forrest.

Olivastri says that habitat loss is another huge concern.

“As we expand corn fields in Ontario, we’re taking meadows and land that is otherwise used by wild creatures, including pollinators.” While the amount of area farmed in the province decreased between 1986 and 2006 by almost five per cent, corn production has increased. According to Statistic Canada, there were 511,194 hectares of corn in Ontario in 1971. By 2011, there were 822,465 hectares. Corn needs no insect for pollination, as they are wind-pollinated or self-pollinating.

Olivastri says that the best way to help native bees in the city is to plant native flowers or just “let your garden ‘bee’.”

“We call it Let It Bee gardening. This time of year, people may want to go out and clean out stock from raspberries, and that’s where some of the solitary bees may be hiding. Leave it.” Olivastri reckons native bees should emerge in the next month.

“It all depends when this cold weather ends.”

[The following map shows the locations of beekeeper associations in Ontario.]