Many residents may not know that in the early part of the 20th century, Ottawa’s neighbourhoods were connected by a network of streetcars carrying people to different parts of the city.

With a sense of deja vu, OC Transpo’s LRT expansion today is a return to an idea of mass transit that was shelved nearly 100 years ago, a decision that started with a pivotal encounter on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had travelled to London to attend the coronation of George VI and Elizabeth in 1936, when he decided to make a side trip to the site of the upcoming World’s Fair in Paris.

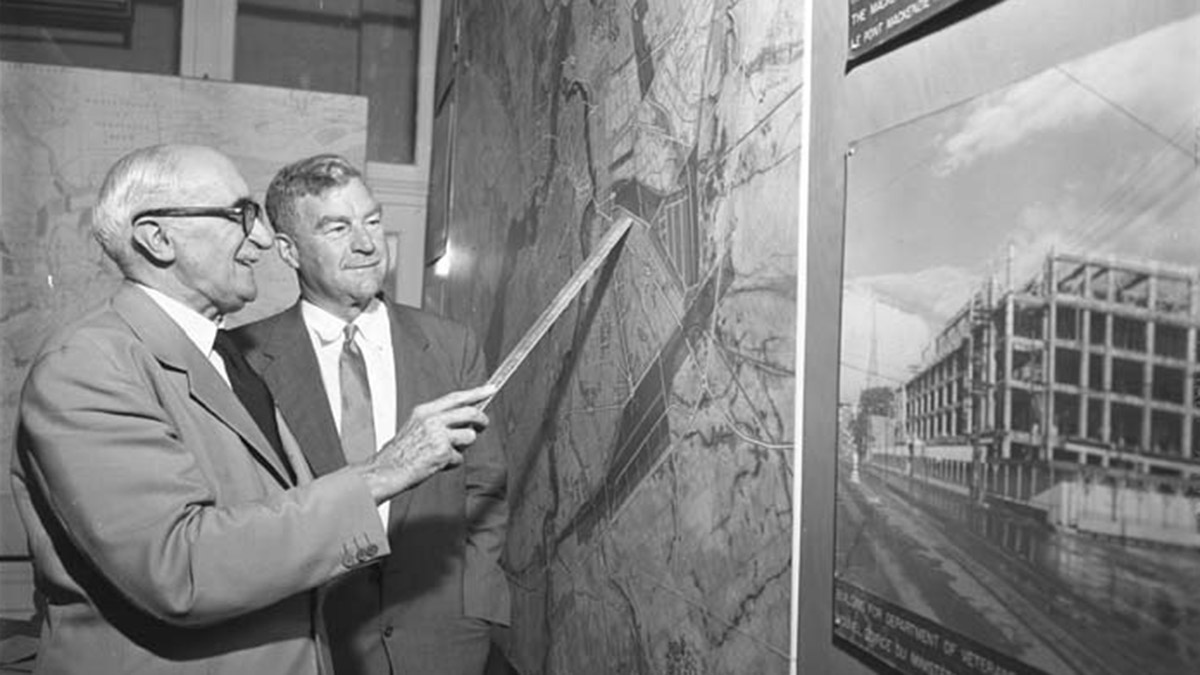

While touring the grounds, King met Jacques Gréber, the fair’s chief architect. From his first meeting with Gréber, King said he knew that this would be the man to make Ottawa a modern capital city. Gréber had previously shaped cities across the United States and France into world-class destinations, perhaps most notably creating Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

Gréber first set foot in Ottawa the following year, to steer the construction of the national memorial for the First World War. But his appointment was controversial.

“The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada objected to a non-Canadian put in this position, but nonetheless, he was put in charge of a group of Canadians as well,” said James Powell, with the Historical Society of Ottawa.

“There was a 17-member National Capital Planning Committee, including reps from Ottawa, Hull, members of professional institutes, including the Royal Architectural Institute and others.”

Gréber returned to France after the completion of the National War Memorial, where he was the country’s inspector general of urbanism before war consumed Europe.

I think that (Jacques) Gréber had a lot of good ideas, but he didn’t anticipate some of the realities that would develop in the future. I think he was too negative about electric streetcars and trains, but then a lot of other people were at the same time. We’ve had a rail renaissance since then.

David Jeanes, Transit Action Canada

As the Second World War ended, King was contending with his legacy as Canada’s longest serving prime minister. He turned his attention to transforming the nation’s capital. Mere days after the end of the war he asked Gréber to return to Canada.

In 1950, the 300-page General Report on the Plan for the National Capital — the Gréber Plan — was officially published.

Gréber had found a lot to love about Ottawa, opening his report by praising the city’s “magnificent setting of intimate, imposing and enchanting scenery.” He also quickly cautioned that “Ottawa’s growth, however, has reached a point of urban development which is rapidly depleting and endangering its natural assets.”

One of the biggest threats to the city’s natural beauty, the report noted, was the unsightly rail network that blighted Ottawa’s downtown. Within 10 years, that rail system would be gone, ending 70 years of use.

The birth, death and rebirth of urban rail

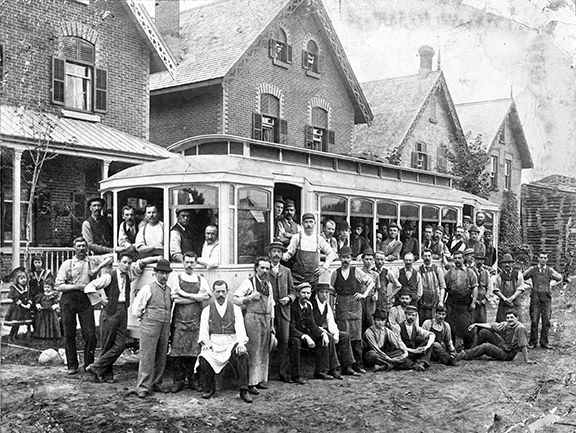

Ottawa’s history of streetcars begins in 1891 when the Ottawa Electric Railway began operating across the city, succeeding the horse-drawn Ottawa City Passenger Railway Company.

“By 1895, Ottawa had 48 kilometres of track carrying 68 streetcars and ridership by the end of that year had increased to 4.1 million,” then-Ottawa mayor Jim Watson told a council meeting in 2022.

Ottawa’s streetcars were a fixture of the city in 1937, when Gréber first visited.

“The first time he came, Ottawa had a very extensive streetcar network,” said David Jeanes, a spokesperson for Transit Action Canada, a national not-for-profit advocacy organization.

“The whole public transit system was based on streetcars rather than busses in the 1930s and the streetcars went to Rockcliffe in the east end, Britannia in the west end and to Bank Street south of the Rideau Canal in the south end.”

Gréber first advocated for the removal of streetcars when planning the National War Memorial.

“Gréber really started the process of getting rid of those lines, starting with Elgin Street because he produced this plan to turn Elgin Street into this ceremonial boulevard,” said Jeanes.

“The streetcar tracks were removed from Elgin Street by 1939 as part of that plan.”

His opposition to rail downtown was not confined to streetcars. He advocated to move Ottawa’s main train station, Union Station, outside the core. Today the historic building serves as the general government conference centre.

“When he came back in 1950, we still had quite a few streetcar lines, but not as many as had been there in the 1930s. But they were all eliminated, essentially as part of the Gréber Plan, and they were all gone by 1959, replaced by diesel busses.”

Ottawa streetcar routes

“During the Second World War, the streetcars were run by a private company that was subject to extra taxes to help pay for the war effort and very little money was put into rebuilding infrastructure,” said Powell. “By the end of the war, they were pretty ramshackle.”

“You had this aging, rickety system downtown already being melded with busses going to the outer parts of the city. Seeing that they’re ugly and these overhead wires obstructed the beautiful views of Parliament Hill, getting rid of them and relying solely on busses is what the city did.”

Although the Gréber Plan influenced Ottawa’s decision to move away from streetcars, cities across North America were making the same decision. The vitality of Ottawa’s streetcar system was further challenged by the fact the Ottawa Electric Railway was privately owned.

The ‘rail renaissance’

“I think that Gréber had a lot of good ideas, but he didn’t anticipate some of the realities that would develop in the future. I think he was too negative about electric streetcars and trains, but then a lot of other people were at the same time. We’ve had a rail renaissance since then,” said Jeanes, with the opening of a light rail system including Line 2 — the Trillium Line — which started operating in January.

Gréber’s calls for the elimination of rail in Ottawa’s downtown core in favour of automobile parkways operated on the assumption of a very different future for Ottawa and rail infrastructure.

“He expected the National Capital Region to only have a population of 500,000 to 600,000 people on both sides of the of the river by 2020 and by 2020 it was 1.4 million people with even more today. So, he got the order of magnitude out by three times the size of what actually happened,” said Powell.

“When Gréber was doing his planning, a lot of the French rail network was still in ruins after the Second World War. What he’d seen was a rail network that had been used for military purposes during the war. Japan had not yet built its bullet train network, that didn’t come until 1964. So, you can’t really blame Gréber for not having a good idea of what the future would be,” said Jeanes.