It’s late April, and the ice covering the Ottawa River has melted, leaving the waterway open for fishing, kayaking and swimming.

As part of the larger St.Lawrence River watershed, the Ottawa River provides vital habitat to at least 24 provincially and nationally endangered species. Its microclimate, sand and limestone bottom sustain rich wetland and forest habitats that support a variety of flora and fauna, according to the Ottawa Riverkeeper’s research.

However, while clean enough to provide recreation and drinking water for communities, this essential environment has a long history of being polluted by microplastics, sewage overflows and nuclear waste.

Larissa Holman, the Ottawa Riverkeeper’s Director of Science and Policy, says her team often hears concerns about the river being ‘dirty or unsafe to swim in.’ As a result, the staff spends a lot of time countering that narrative by providing data that shows just how clean the Ottawa River is from a swimming and access perspective.

“This river holds a lot of recreational value for people who are lucky enough to have access to it,” said Holman.

Given its massive importance to surrounding communities, she added, it must be properly appreciated and cared for and not necessarily seen as a threat.

However, this goal is easier said than done.

For example, a Canadian nuclear research facility is beside the Ottawa River near Chalk River, ON.

“We have a facility right on the edge of the Ottawa River, which continues to develop and work on nuclear technologies,” said Holman. “As that is happening, we want to ensure that appropriate protections are in place to ensure that as little as possible radioactive waste ends up in our freshwater environments.”

The site was opened in 1944, about 200 kilometres upstream of Ottawa and Gatineau. Early disposal practices at the site generated numerous radioactive waste plumes that uncontrollably migrated — contaminating wetlands, groundwater, surface water and streams draining into the Ottawa River.

Most recently, the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories has proposed building Canada’s first permanent nuclear waste dump, termed the “Near-Surface Disposal Facility,” less than a kilometre from the Ottawa River.

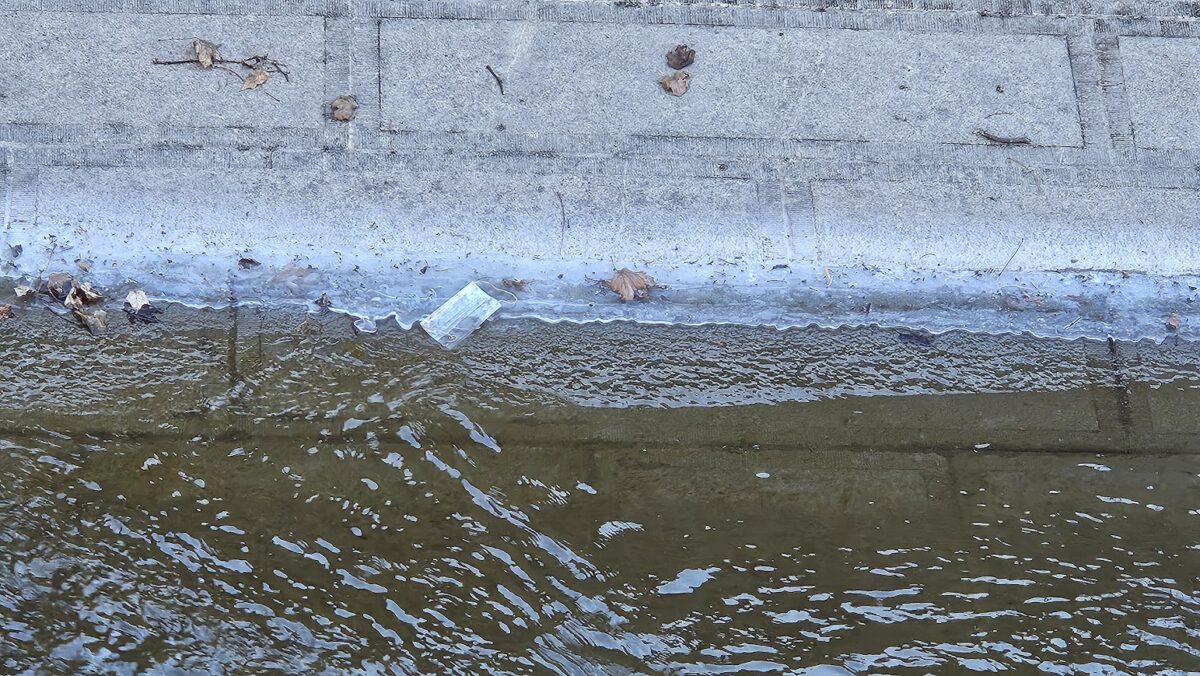

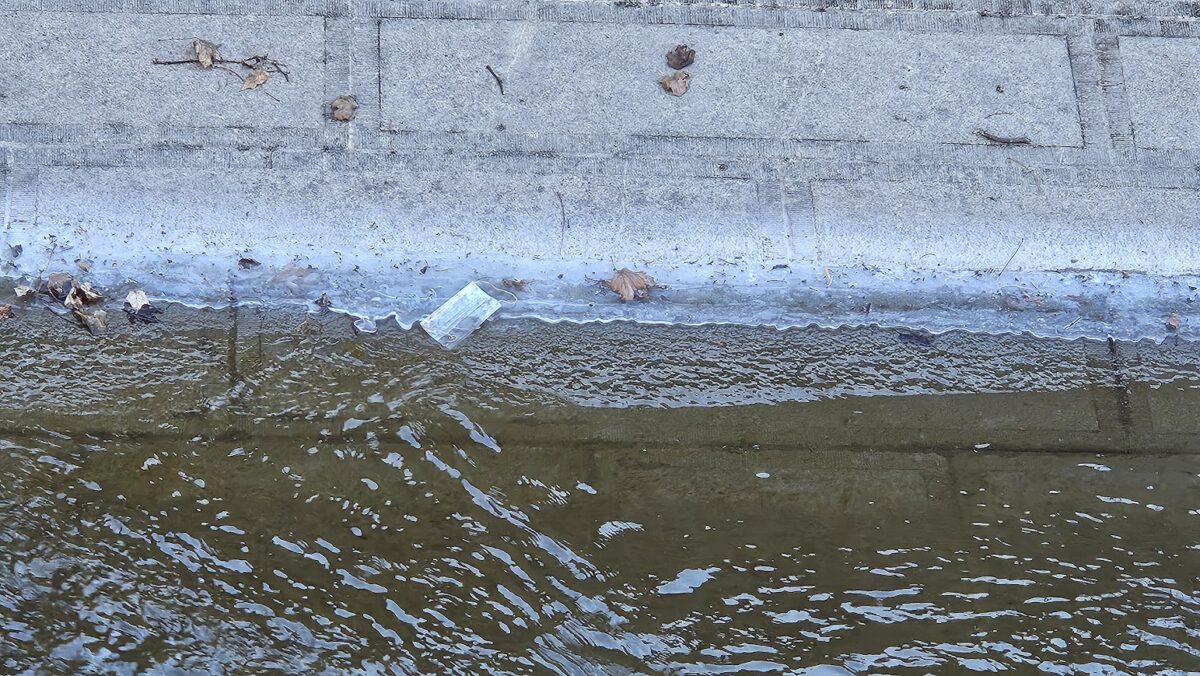

Holman also says that microplastics, common and challenging to remove, are another significant issue in the waterway.

“Plastics have a lot of contaminants associated with them,” said Holman. “So, the real concern is how do we keep these plastics out of freshwater environments.”

In 2016, Ottawa Riverkeeper’s Riverwatch Network of volunteers teamed up with Dr. Jesse Vermaire’s lab at Carleton University to study the presence of microplastics in the Ottawa River. The study, published in the journal FACETS in 2017, found that plastic pollution in the river and its major tributaries in the National Capital Region is prevalent and at concentrations more significant than those reported for many other freshwater systems, including the Great Lakes.

Of these samples obtained from the watershed’s main tributaries, Holman added that most plastics were microfibres and nearly impossible to remove.

A subsequent 2023 study that looked at plastics in shore sediments of large watersheds did show that the Ottawa River’s watershed was not retaining many plastics, mainly because of the high seasonal flow rates and size of the river basin, its lower population base compared to other researched freshwater watersheds and the relative size and discharge of the Ottawa River.

Still, these findings do not mean microplastics have been removed from the environment just that they don’t remain present, said Holman.

Holman argued that one fundamental way we can reduce the introduction of plastics and their microfibers into the waterway is by preventing sewage overflows, which contain wastewater from washing synthetic materials.

Holman argued that one fundamental way we can reduce the introduction of plastics and their microfibers into the waterway is by preventing sewage overflows, which contain wastewater from washing synthetic materials.

Although wastewater treatment plants remove most of the materials from municipal wastewater, Holman warned they cannot remove all contaminants.

This lack of filtering is troubling for Ottawa’s sewage management, which has faced contamination controversies for more than a century. Before the city’s first sewage disposal plant at Green’s Creek opened in 1963, every litre of waste flushed into Ottawa’s sewer system ended up in the river.

She said overflows common in municipalities with older infrastructure can threaten the river’s health by releasing pathogens, bacteria, and contaminants directly into the river before treatment.

Holman argued that one fundamental way we can reduce the introduction of plastics and their microfibers into the waterway is by preventing sewage overflows, which contain wastewater from washing synthetic materials.

Although wastewater treatment plants remove most of the materials from municipal wastewater, Holman warned they cannot remove all contaminants.

This lack of filtering is troubling for Ottawa’s sewage management, which has faced contamination controversies for more than a century. Before the city’s first sewage disposal plant at Green’s Creek opened in 1963, every litre of waste flushed into Ottawa’s sewer system ended up in the river.

She said overflows common in municipalities with older infrastructure can threaten the river’s health by releasing pathogens, bacteria, and contaminants directly into the river before treatment.

In late 2020, the city designed a Combined Sewage Storage Tunnel, the CSST, to help prevent overflows. By connecting the tunnel to the most active and high-volume combined sewage overflow locations in its service area, it functions as an underground, linear storage facility that intercepts and stores surface runoff and wastewater until the Robert O. Pickard Environmental Centre can treat it. Once cleaned, it is returned safely to the Ottawa River.

Nevertheless, overflows continue, the most recent on Sept. 19, 2023.

Holman explained that the City of Ottawa has taken significant action to address some of these central issues, particularly sewage overflows, and ensure the water is safe. Still, there will always be ways to improve.

“For any municipality, the big ones are around development and making sure that development happens in places that do not really come into conflict with areas where there are species at risk nearby or take into account the impact that those developments have on the greater waterways that they’re next to,” said Holman.

Voices: A beloved waterway

For those living near the Ottawa River, the waterway is a place to reconnect with nature and escape the stress of a fast-moving society.

Brenda Vellino, a faculty member in English and the Human Rights and Social Justice program at Carleton University, often walks beside and swims in the Ottawa River. She says she has also come to know the river as the Kiji Sibi, which is a more than 1,000-kilometre heartline connecting Algonquin Territory on both sides of the river and a critical marker to her of Algonquin relations with the natural world and with their territorial guardianship.

Her other main river relationship is with the Rideau River (Pasepkedjiwanong). The Rideau runs past the Carleton Campus and through her neighbourhood in Old Ottawa South in its path north into the Kiji Sibi.

“During the pandemic, walking alongside this river and on it when it was frozen for two months, I developed a deep sense of gratitude for the river. It is a magnet for waterbirds and other bird species in the trees along the river, including migrating loons and wood ducks, great blue herons, little green herons, egrets, and cormorants,” said Vellino.

“I also ski on the river in winter and swim in the river in summer. Both of these experiences give me a sense of the spaciousness and power of the natural world within the urban world.”

She added that she is watching the Chalk River nuclear waste storage controversy because of the involvement of Algonquin leaders who are standing up for water rights on both sides of the Kiji Sibi, from signing petitions on this issue to reading briefings.

“I really hope that Canadian Environmental Law, along with the laws of the Algonquin Anishinaabe water protectors, will be enough to stop the dangerous nuclear waste storage at Chalk River, which has the potential to contaminate the drinking water as well as the multi-species worlds of all the other creatures,” said Vellino.

Most importantly, Vellino wanted other Ottawans to be aware that human bodies are 60 per cent water, and the water we drink comes from the Kiji Sibi. Thus, she said a public education campaign that makes people fully aware of this as a reason for protecting the water and giving thanks to the waters every day is vital.

Aria Platts-Boyle is a fourth-year Communication and Media Studies student who moved to Ottawa from Muskoka in 2020 to attend Carleton University. Although she does not often visit the waterway in the winter, she said she usually frequents the Ottawa River near Parliament Hill during grocery runs or visits Rideau River near campus to study, spend time with her friends and fish in the summertime.

She says she worries about fishing in the Rideau and other local waterways because of the almost indistinguishable and greyish fish she has hooked.

“I definitely think even though the water might be like ‘clean,’ if the animals in it are not functioning like they should normally and looking healthy, there definitely needs to be better upkeep,” said Platts-Boyle.

She’s also concerned with the city’s management of sewer overflows and bateria levels in warmer months, which prevents her from swimming, something she loves.

“I love swimming, and I would love to go swimming in Ottawa more,” said Platts-Boyle.

Sun Na is from Halifax and was visiting Ottawa to see his family when he spoke to Capital Current. He said that water is part of his everyday life as he often walks near the ocean in his hometown. He also likes to walk along the river or canal when he is in Ottawa.

“It really refreshes my mind,” said Na.

He says he believes the city should do more to protect the river. He hopes that citizens will not put the issue aside and make more of an active effort to address pollution in the river.

Conservation for the long term

To protect the Ottawa River from harm, the Ottawa Riverkeeper and residents have recommended several ways to aid in its long-term conservation for the humans and non-human species living in or near it.

From studying the Ottawa River and its health through community-based monitoring programs to applying the findings to influence efforts at a regulatory level — for instance, actively submitting on the Federal government’s new Radioactive Waste Policy and presenting to parliamentary committees on various issues — Holman said the Ottawa Riverkeeper has intervened at many different levels to help protect the river for years to come.

However, she says it’s not enough. Increased efforts by the city and locals are now essential.

“Ottawa has a lot more resources available than many of the other municipalities that it could help provide or share to make sure that everybody is working with the same tools, and so I think that from the city’s perspective, this is something it could be doing,” said Holman.

“But also from residents’ perspective, there’s the fact that we are in the nation’s capital, and many of us in this city work alongside or know people who work at various levels of government, and the government is making policies every day that is impacting this river, and freshwater systems across the country.”

Holman also suggested many other ways people can address plastic pollution, including through shoreline cleanups or by reducing littering.

Platts-Boyle noted that the city could encourage people to be more conscious about what they put in the water systems and reconnect with nature.

“From even what type of detergent they are using to buying less polyester and stuff like that can help with microplastics,” said Platts-Boyle. “And I think encouraging people to just spend time with it, like going and being in nature more, is really important.”

For Vellino, protecting the Ottawa River for the future goes beyond conservation. She said it is vital also to consider how the river aids the survival of all species that rely on it and act more holistically.

“I think cultivating river relations so that people feel they can come to know the rivers in this city as living beings in all seasons and learn to love these rivers as a foundation for caring about them as more than just a place for leisure activities, but a place where multi-species live,” said Vellino. “There are likely many collaborative studies with bird, fish, amphibian, insect, plant, and aquatic biologists that could tell us stories about the current health of the rivers for the multi-species world and how to improve this.”

The Lake Sturgeon, for instance, is one of many at-risk species in the Ottawa River watershed that the Ottawa Riverkeeper is working to protect.

The Lake Sturgeon is the largest freshwater fish in Canada, measuring up to two meters long and weighing up to 180 kilograms. However, harvesting, habitat loss, poor water quality, dams, and other barriers have caused the Lake Sturgeon to decline in North America, especially in Ontario, where they are now endangered, according to the Ontario‘s official webpage.

It is a bottom feeder and, as such, faces more significant exposure to high levels of contaminants and pollutants. For instance, the uptake of bethos contaminants in sturgeons could have harmful effects, including growth retardation, muscle degeneration and reproductive impairment, according to the province’s Lake Sturgeon Recovery Strategy.

Nonetheless, it is still possible to bring awareness and protect species, like the Lake Sturgeon, threatened by human activities for long-term conservation.

“I think there are a lot of folks who, for no fault of their own, really don’t have a strong understanding of the threats to the rivers and lakes in this country and what steps can be done to protect them better,” said Holman. “So there’s a lot that people can do on an individual basis, but also at a government level that can provide better protections.”