Ontario Premier Doug Ford secured a historic third straight majority government after winning a snap election on Feb. 27.

In a vote that saw the second-lowest voter turnout in provincial history, Ford’s Progressive Conservatives won 80 of 124 seats in the legislature, the NDP captured 27, the Liberals 14 and the Green Party two. One independent MPP was elected.

Ford called the election 16 months earlier than required. At the time of the election call, opposition parties and other critics said the result would be a disengaged electorate and low voter turnout. But the PC leader argued he needed a strong mandate from Ontarians to deal with threat to the economy posed by U.S. President Donald Trump.

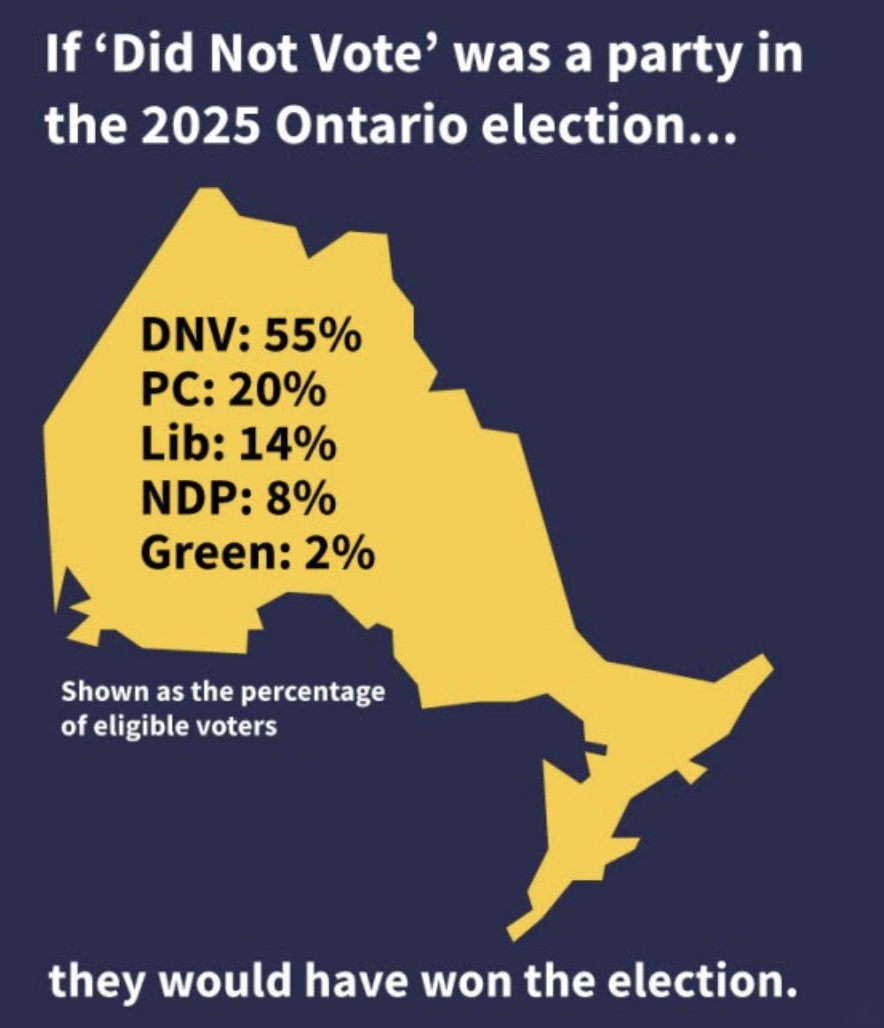

Ford obtained his majority mandate, but only about one in five eligible voters actually cast a ballot for the Progressive Conservatives, according to Elections Ontario. Just over five million of about 11 million made the trip to a polling station and fewer than 2.2 million of those voters — 43 per cent of the votes cast, representing the choice of just 20 per cent of the electorate — went to Ford’s Tories.

Overall voter turnout was well below 50 per cent for the second straight time in an Ontario election.

“Voter turnout was 45.4 per cent,” noted Fair Vote Canada, a group that advocates for the scrapping of Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system in favour of a proportional representation model in which a party’s seat count would more closely match the proportion of its popular vote.

“That means the current ‘majority’ government (in Ontario) is supported by 20 per cent of eligible voters. In a winner-take-all electoral system, many people feel they must vote for the lesser evil, or are discouraged from voting at all.”

The organization produced a graphic following the election to illustrated the fact that if the 55 per cent of eligible voters who didn’t cast a ballot formed their own political party, “Did Not Vote” would have won the election in a landslide.

The 45.4 per cent turnout was the second lowest in the province’s history, after the 2022 election which holds the record low at 44.06 per cent.

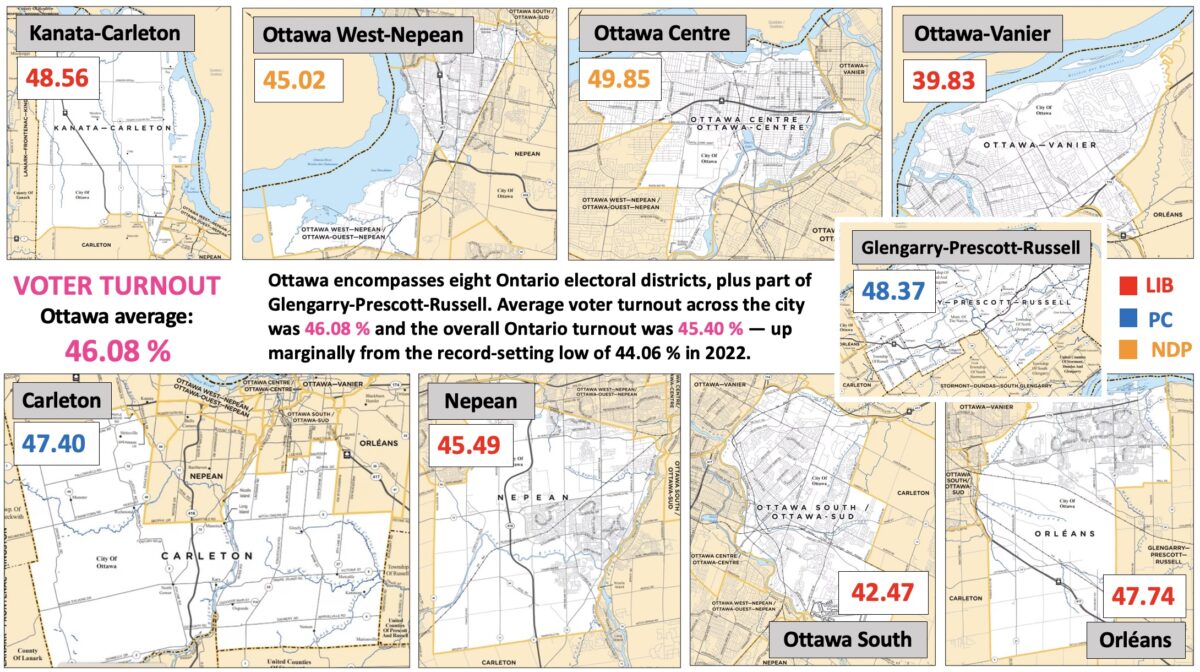

And for the first time ever, fewer than half of the eligible voters in all nine of Ottawa’s ridings showed voted. The average turnout rate across the city’s nine electoral districts — including Glengarry-Prescott-Russell, which lies largely outside of Ottawa but includes parts of the city’s former Cumberland township — was 46.08 per cent.

Ottawa-Vanier had the worst turnout in the city, at 39.8 per cent. That riding has sent a Liberal to Queen’s Park in every election since 1971, including this past one. The highest turnout was in Ottawa Centre, where 49.85 per cent of eligible voters participated electing former city councillor and mayoral candidate Catherine McKenney to sit in the official opposition NDP caucus.

Some ridings in Ontario were so closely contested that the decisions of a mere handful of voters not to cast a ballot may have decided the outcome. In Northern Ontario’s Mushkegowuk-James Bay riding, the NDP incumbent appears to have held off a PC challenger by just eight votes.

And in Mississauga-Erin Mills, the PC incumbent is just 20 votes ahead of the Liberal candidate.

Both ridings will see automatic recounts under the Election Act, with final results confirmed by March 17.

While the close results in those two ridings are particularly striking, every race in Ottawa was decided by a margin of fewer than 20,000 votes, far less — in every case — than the number of eligible voters who decided not to participate in the election.

Because of low voter turnout in recent years, the question of how well provincial elections represent the desires of Ontarians has been widely discussed. After the 2022 election, Ontario’s top election official called for recognition of low turnout as a serious problem.

“In these past few years, electoral management bodies and key players in the democratic ecosystem have learned to adapt to abrupt global events such as COVID-19, yet there is another epidemic afflicting democracies worldwide— that of declining voter engagement and turnout,” the province’s chief electoral officer, Greg Essensa, stated in his report on the June 2022 Ontario election.

“Although there are now more countries that host elections for a growing number of electors, voter turnout has decreased significantly since the early 1990s,” he noted. “Ontario was not exempt from this trend and, in this last election, 44 per cent of Ontarians cast their ballot, marking the lowest recorded voter turnout in the province’s history. While I have always maintained that voter turnout is a shared responsibility, more can and should be done to address elector engagement.”

Essensa added: “From political parties and candidates, to electors, legislators, and administrative bodies such as Elections Ontario, we all have a role to play in Ontario’s democratic process. This means not just acknowledging the declining electoral participation that we see in democracies around the world and here at home but also doing our part to protect and to strengthen the health of our democracy.”

However, voter turnout for the Feb. 27 election was only slightly higher than in 2022, making clear the problem raised by Essensa three years ago remains unsolved.

Catherine Corriveau, a senior manager for policy and strategic initiatives with the Democratic Engagement Exchange at Toronto Metropolitan University, says low voter turnout is a difficult problem with no single solution.

From political parties and candidates, to electors, legislators, and administrative bodies such as Elections Ontario, we all have a role to play in Ontario’s democratic process. This means not just acknowledging the declining electoral participation that we see in democracies around the world and here at home but also doing our part to protect and to strengthen the health of our democracy.

— Greg Essensa, chief electoral officer of Ontario, after 2022 election

The DEE is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that has worked with electoral commissions across the country on increasing participation in elections.

One 2021 study of national-level elections in the journal Political Behavior found strong correlations between voter turnout and 22 different variables such as inflation, the level of economic globalization and compulsory voting.

The study also found that if an election appeared close, it would decrease turnout. Yet an Elections Canada survey of non-voters in the 2000 election found that a competitive election should increase turnout.

The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance also argues that competitive elections lead to increased turnout. It cites 15 other factors that affect turnout, including age, economic development, education and the amount of money parties and candidates spend on campaigns.

Despite the complexity of the issue, Corriveau says there are concrete steps to be taken. In the Feb. 27 election in Ontario, she worked with Elections Ontario to reach students on 49 campuses across the province and encourage them to vote.

Community engagement with voters is key, Corriveau says. Multiple surveys in the past decade or so have shown that a high number of young Canadians report feeling lonely.

“They don’t necessarily feel like they have a strong sense of belonging or they’re connected with their communities, and there’s a direct correlation to people not voting as a result of that,” said Corriveau.

Corriveau highlighted the decline of local media as another problem for voter participation. Hundreds of small media outlets across Canada have shut down over the past 15 years as a result of financial pressures linked to the rise of digital advertising and the collapse of newspapers’ traditional revenue model.

Local media is important for highlighting specific issues that are important to voters and generating engagement around those issues, says Corriveau. “Those are not just big issues that impact the province and that have nothing to do with them, but (they are issues) that can dictate specific outcomes for the riding itself.”

Corriveau remains optimistic about voter turnout in Ontario.

“Sure, the number is low,” she says. But she says people should look beyond the number of voters and pay close attention to community-level and social factors that affect whether people vote.

“It’s not just the weather. The weather’s a thing, but it’s not just the weather,” she said.

Beyond turnout, however, the fact remains that the party forming the next majority government did not receive the majority of votes. Nor will the party that received the second most votes form the official opposition. The Liberals, with almost 573,000 more votes than the NDP, just barely regained party status with 14 seats. Official party status requires a minimum of 12 seats in Ontario under the Legislative Assembly Act.

Liberal Leader Bonnie Crombie won’t have a seat in the legislature, having lost in Mississauga East-Cooksville. However, she received unanimous support as leader from party members in a vote on March 2. The party cited its high share of the popular vote as justification for its continued confidence.

But again, because of the low voter turnout across the province, the 1.5 million votes cast for the Liberals represented the explicit support of only about 14 per cent of eligible voters in Ontario.