Standing at the podium in a multi-coloured and brightly patterned Ankara vest, CBC reporter Omayra Issa commanded the attention of the audience that had gathered to hear her deliver this year’s Kesterton Lecture.

Held annually by Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication, the Sept. 27 address marked the first time the lecture was given by a Black journalist. And as she recounted her journey bringing the award-winning Black on the Prairies project to life, Issa didn’t hold back.

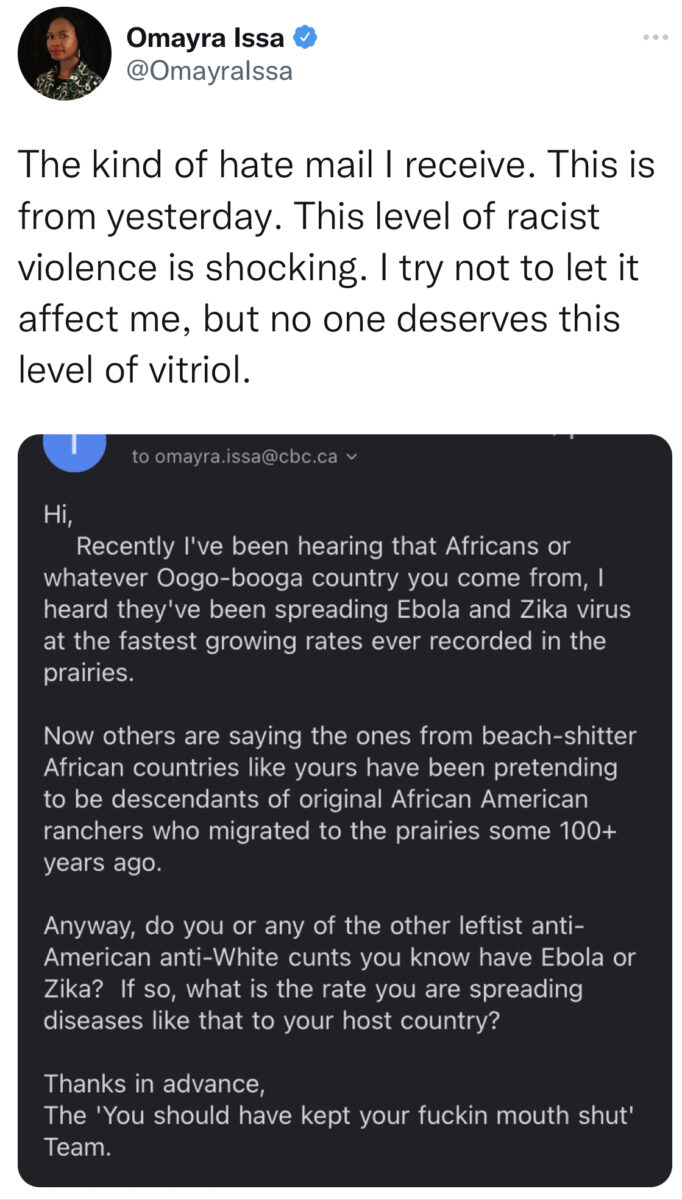

Released in 2021, the multimedia project garnered much acclaim for spotlighting the little-known history of Black communities in Canada’s Prairie provinces — but it also placed Issa in the crosshairs of an angry fringe that took issue with centring Black voices in the larger Canadian conversation.

“Bearing witness has come at a cost,” Issa said as she described the torrent of racist and misogynist bile — including death threats — that flooded her inbox following the project’s launch. “When I embarked on my career as a journalist about a decade ago,” Issa told the crowd, “I didn’t anticipate that my work would lead to threats against my safety in our country.”

Issa’s case isn’t an isolated one. A November 2021 IPSOS survey on online harassment faced by journalists and other media professionals found that 34 per cent of respondents had received online threats within the past 12 months, with female reporters being at a higher risk for online abuse. A UNESCO report released around the same time indicated that 20 per cent of women journalists reported having been attacked offline, suffering harassment, abuse, intimidation — or worse — in person.

While journalists can expect to face pushback when engaging the public, the threats levelled at Issa and others like her have gone far beyond the realm of criticism and seem designed to silence women and racialized journalists.

For Brent Jolly, the president of the Canadian Association of Journalists, a consequence of these threats going unaddressed is reporters potentially feeling the need to self-censor to avoid becoming a target — which is why he argues such threats should be considered a press freedom issue.

“The fact that it’s been allowed to grow and metastasize in the public sphere is something that is now coming to roost on our doorsteps,” says Jolly, adding that the industry is already grappling with concerns surrounding representation and diversity. “I think this is about retention and making sure that various racial and ethnic-diverse groups are included, and have their voices reflected in Canada’s civic dialogue.”

In September, several journalists victimized by hateful threats and the CAJ drafted an open letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau calling for government and law enforcement agencies to combat the growing problem because “hate and threats hurled at journalists have a chilling effect that is bad for democracy,” the statement said.

“The volume and nature of the rhetoric in the recent string of attacks has caused many journalists, as well as their respective organizations, to fear for their safety,” said the open letter, signed by news outlets from across Canada, as well as a national coalition of journalism schools and other professional associations. “We are asking police forces to take several immediate steps to address the current incidents and to work with our organizations to combat abuse of journalists and all victims of online hate and harassment.”

Trudeau responded that “our government strongly condemns these campaigns and the deeply troubling actions of the people behind them.”

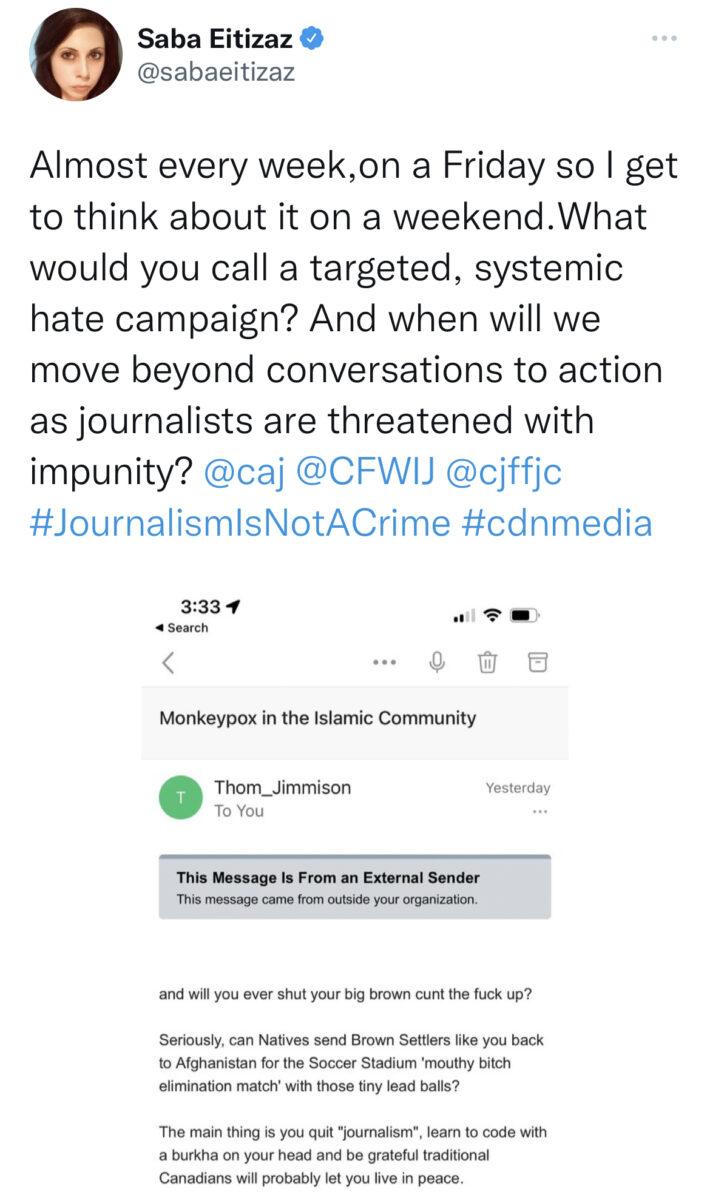

Among those at the forefront of the issue is Saba Eitizaz, co-host of the Toronto Star‘s This Matters podcast. She was among a trio of journalists — including Global News’ Rachel Gilmore and Hill Times columnist Erica Ifill — who spearheaded a newsroom-led effort to combat online harassment that sparked the open letter and prompted a September meeting with federal Minister of Public Safety Marco Mendicino. Despite ongoing efforts within the industry to address this issue, Eitizaz believes that the Canadian news media has yet to fully grasp the deeply racialized and mysogynistic nature of the threats.

“It’s very different from a random incident of hate or criticism. It was highly sexualized, highly violent, misogynistic, racist, Islamophobic content designed to shrink spaces for us.”

— Saba Eitizaz, journalist, Toronto Star

“It pointed to a very systemic and organized campaign against certain journalists, most of them were racialized, or women or from some other marginalized communities,” Eitizaz said of the messages compiled and presented at the meeting with Mendicino. “It’s very different from a random incident of hate or criticism. It was highly sexualized, highly violent, misogynistic, racist, Islamophobic content designed to shrink spaces for us.”

In recent years, many observers have pointed out how the increase in online violence is occurring in parallel to a growing distrust in journalists in some sectors of society – a symptom of rising anti-establishment sentiment spreading in Western democracies. One of the key issues highlighted in UNESCO’s 2021 report is that some political leaders have contributed to this trend and are responsible for “instigating and fuelling some of the worst attacks on women journalists.”

While combative interactions between press and politicians are a hallmark feature of political life in the United States, a similar anti-media rhetoric has made its way from south of the border into Canada’s mainstream political discourse.

When People’s Party of Canada leader Maxime Bernier tweeted last September the emails of three Canadian journalists and encouraged his followers to “play dirty,” his actions bore an unsettling resemblance to the adversarial relationship that had come to define interactions between reporters and many Republican lawmakers during and after the 2017-21 presidency of Donald Trump. The targeted Canadian journalists, who were covering Bernier’s campaign during the 2021 federal election, had evidently offended the former Conservative cabinet minister after highlighting concerns about PPC endorsements from white supremacist groups and the party’s pushing of far-right views.

The journalists almost instantly saw their inboxes flooded with a threatening message, some with racist and sexist language.

Fast forward a year and little seems to have changed.

When reporters covering a Conservative party press conference held by new leader Pierre Poilievre were informed he would not be taking any questions, Global News chief political correspondent David Akin shouted out his questions anyways. Poilievre eventually acquiesced and took two questions, but not before dismissing the former Sun Media national bureau chief as a “liberal heckler.” Akin, who later apologized, was reported to have told Poilievre’s staff “we are not his f***ing stenographers.”

To Karyn Pugliese, editor-in-chief of Canada’s National Observer, Akin’s approach may have lacked tact, but she added, the exasperation fuelling his outburst resonated with journalists across the country. In a column headlined “Who the hell calls a press conference then tells reporters they can’t ask questions?” Pugliese accused Poilievre of trying to “muzzle the press” and “cheat citizens.” Not long after the piece was released, a confrontation with a member of the public highlighted the potential real-life risks that accompany reporting on such issues.

“A woman stopped me outside my building, and got in my face, started swearing at me and telling me I was a liberal,” said Pugliese, recalling how she felt caught off guard, wondering whether she had joined the growing list of targeted journalists. “I think there’s a fear right now that the targeting of journalists can spill over into real-life violence.”

According Eitizaz, the connection between anti-media rhetoric employed by politicians and the increasingly hostile reporting environment cannot be understated.

‘I think there’s a fear right now that the targeting of journalists can spill over into real-life violence.’

— Karyn Pugliese, editor-in-chief, Canada’s National ObserveR

“Right after Maxime Bernier openly doxed journalists, all of the journalists he named (were) immediately flooded with hatred,” said Eitizaz, adding that this kind of political rhetoric fuels and exacerbates existing distrust. “When you platform hate, you’re legitimizing it and you’re giving reasons for people to continue to glom on to that movement.”

For Pugliese, the unfortunate reality is that there’s a limit to what newsrooms can do to protect reporters. Until appropriate measures are implemented, she said, much of the onus will continue to fall on the shoulders of women and racialized reporters who need to be aware of the situation as they enter the industry.

“Nobody wants to be told not to cover politics or told not to challenge politicians, when politicians need to be challenged, (just) because they’re going get blowback,” said Pugliese. “I think that you’re really going have to make a choice when you’re coming into the business (that) you’re going to be comfortable with that kind of pushback, because it just seems to be where we’re at.”