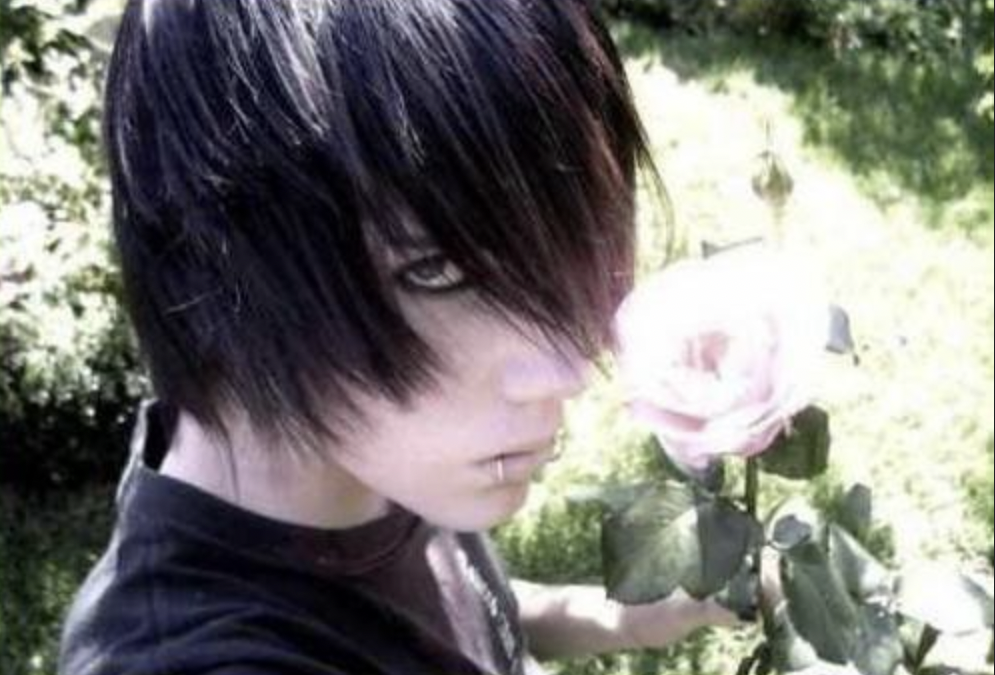

“Emo” is a largely American, music-based subculture that gained traction in the early 2000s. The subculture eventually went global, before fading into the background by 2015.

Fading into the background that is, until recently.

Social media channels such as TikTok have seen a revival of emo influencers and culture, courtesy of Gen Z fans. Even here in Ottawa, The Twenty-Seven Club hosts ‘Emo Night’ every third Saturday.

In Texas, a yoga teacher recently began offering ’emo’ yoga classes. The classes sold out by the third month and are now being held bi-weekly to accommodate the demand.

Even as emo was rising in popularity, embracing its values and dressing in its style was a one-way ticket to relentless bullying — bullying that was often violent in nature.

The controversial nature of this subculture was apparent in the way “emos” were talked about and treated, but why was this subculture so hated by so many?

As someone who grew up as an emo, it’s a question that’s been on my mind for years.

To find an answer, it’s important to understand the beginnings of this subculture and the political climate from which it erupted.

Emo technically began in the 1980s, but only gained wider popularity in the early 2000s, when the band My Chemical Romance — MCR for short — was formed in New Jersey.

The musical style is a sub-genre of punk-rock, punk being described by Merriam-Webster as “rock music marked by extreme and often deliberately offensive expressions of alienation and social discontent.”

Punk music is often political in nature, and expresses frustration with the world at large through a musical expression of anger.

Emo turns punk on its head by radically expressing sorrow and depression with just as much power. It also takes on a political focus like punk rock sometimes. On the emo spectrum, some artists are more mellow and melancholic than others, but this more “emo-tional” writing is what defines the sub-genre.

So despite Way’s aversion to the label, most of MCR’s music still falls under emo because of the writing, even if the sound is more pop-punk/punk-rock.

Sorry Gerard.

It’s also important to note that emo, while having similar aesthetics to goth fashion, is not related to the goth music or culture. In fact, during the rise of emo, goths in general hated being compared to emo and were largely against it.

Despite how emo was commonly perceived from the outside, it is inherently connected to politics and revolutionary themes, largely centring around freedom and liberation of one’s authentic expression.

I think emo is and was not just a meaningless expression of pain. Emo was an anti-conservative rebellion, a reaction to the AIDS crisis and a world profoundly shaken by the 9/11 terror attacks in September 2001.

To understand how the collective trauma of both the AIDS crisis and 9/11 created both emo and the hatred towards it, we have to look at the effects of both events on political culture and fashion.

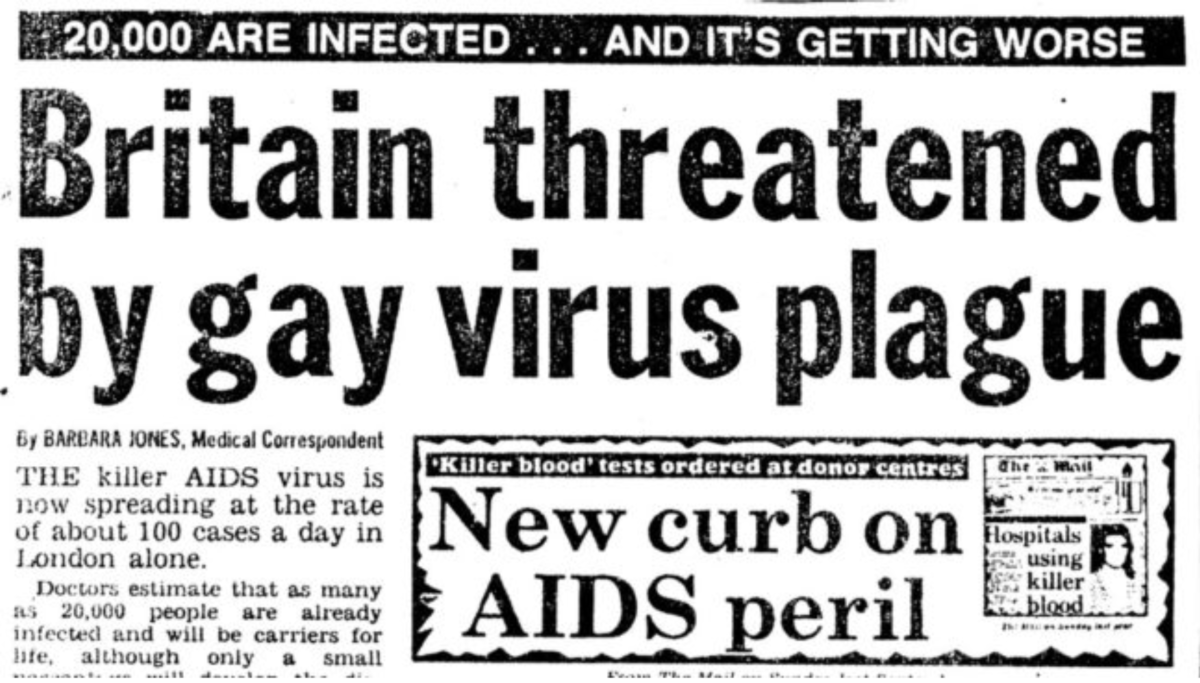

The first known cases of AIDS were reported in the early 1980s, devastating individuals and communities as the crisis reached its height in the 1990s and very early 2000s. The disease disproportionally affected gay communities, particularly gay men. This reignited homophobic rhetoric in popular culture, with some well-known newspapers unabashedly calling AIDS a “gay plague” and other such terms.

The wave of fear and panic created by the crisis manifested itself as a renewed prejudice towards the gay community. This anxiety seeped into popular fashion in the 1980s, where the trend became the ‘athletic’ body for men and women. The trend in the ’80s was all about looking as athletic and healthy as one could. The goal, it seemed, was to look as different as one could from an early AIDS patient. Magazines at the time focused on large, strong muscles and toned, sun-tanned bodies.

The homophobia of western culture reignited by the AIDS crisis was not the only event that resulted in the creation (and ultimately hate) for emo.

Another important tragedy that marked the beginning of emo’s popularity was the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York. This event invigorated emo with new passion and brought it into the public eye.

Like the AIDS crisis, the tragic events of 9/11 inspired a renewed conservatism that was largely patriotic and fearful of the ‘other’. In my opinion, the renewed fear and suspicion toward the Middle East extended to all things non-traditional, non-American, and non-Christian. There seemed to be a real paranoia of anything that threatened traditional values.

Yet, at the same time, a counter-reaction was brewing that would eventually go global.

Way, MCR’s lead singer, was taking a commuter train when he witnessed the towers fall. He has said in numerous interviews that My Chemical Romance was born out of this event, as it motivated him to create art that meant something.

The band was formed that year, and with its growing popularity emo exploded.

Fans represented a reaction against the conservative ideals pushed in American society and other countries. Unlike the ‘athletic’ fashion trend of the 1980s, emo aesthetics were all about very thin, very pale, almost sickly frames.

Emo style fully rejected this superficial image. It instead wanted to portray the sickness and pain inflicted by society with a darker aesthetic.

There was no apparent fear of looking like an early AIDS patient. In fact, the sub-culture itself was infamous for having a large number of teens identifying as bisexual. The homophobia of the AIDS crisis and the conservative community didn’t stop these teens from living their truth as queer individuals.

In light of 9/11, the fear of the ‘other’, and the homophobic remnants of the AIDS crisis, emo embraced queer identities and rejected all forms of conservatism. Emo did this by openly embracing the dark, the depressing and the socially unacceptable.

Emo acted as an open protest against a conservative society that hid its authentic feelings and pain and conformed to social conservative norms.

The emo sub-culture boldly rebelled against narrow, mainstream ideals, and embracers of emo actively portrayed themselves as an ‘other’.

Emo as a counter-reaction to conservatism explains its creation, but also the massive pushback the subculture would face.

Emos were commonly misunderstood as belonging to a kind of death cult, with accusations of devil worship and glorifying suicide. Criticism often contained undertones of homophobia, as well. This resulted in a sort of smear campaign against emo, with certain school boards and countries trying to ban emo, and panic among parents who were afraid their kids would join the emo ‘cult’ and be lost to suicide.

The remnants of the AIDS panic also played a major role in the violent and persistent bullying emos faced, as homophobic slurs were commonly thrown at emos not only in America, but around the globe.

In 2008, riot police in Mexico had to defend emo kids in several cities from mobs that launched a series of violent attacks. The perpetrators of the violence were mostly self-proclaimed punks and rockers, who had an issue with emo. However, in the TIME article, “Mexico’s Emo-Bashing Problem”, Mexico City youth worker Victor Mendezo said that despite the conflict appearing to be a war of musical genres and subcultures, the issue was really about conservative homophobia in Mexico.

“At the core of this is the homophobic issue,” he said. Mendoza argued that, “this is not a battle between music styles, at all. It is the conservative side of Mexican society fighting against something different.”

The skinny, pale and openly queer culture of emo challenged mainstream society, appearing to be a harbinger of illness and doom, and there was a heavy homophobic pushback against the sub-culture all over the globe.

Reminiscent of its rise in the wake of the AIDS crisis, emo made a comeback amid the global COVID pandemic and after the political turmoil in the U.S. under former Republican president Donald Trump.

Emo remains a reaction to collective trauma and a rebellion of authentic expression and truth. Emo is a recognition that we, as a society and culture globally, are not OK — and we shouldn’t pretend we are just to fit the idealized image of a perfect, controlled society.

Emo is a rebellion that strikes a chord; whether your reaction to it is positive or negative, depends on you.

But sometimes — as an MCR hit once put it — it’s okay to be “not okay.”