Mobina Akbari, the director of Social Development and Better Future for Afghanistan, was 14 in 1998 when the Taliban first took over the country and imposed a rule that banned her from returning to the ninth grade. With no other choice, she said girls in her neighbourhood had to rent books together to afford to continue reading.

“Financially, all the family was under zero, so even 5000 Afghani and 24 hours, it was very expensive for us to pay for that,” said Akbari, explaining the cost of a borrowed book.

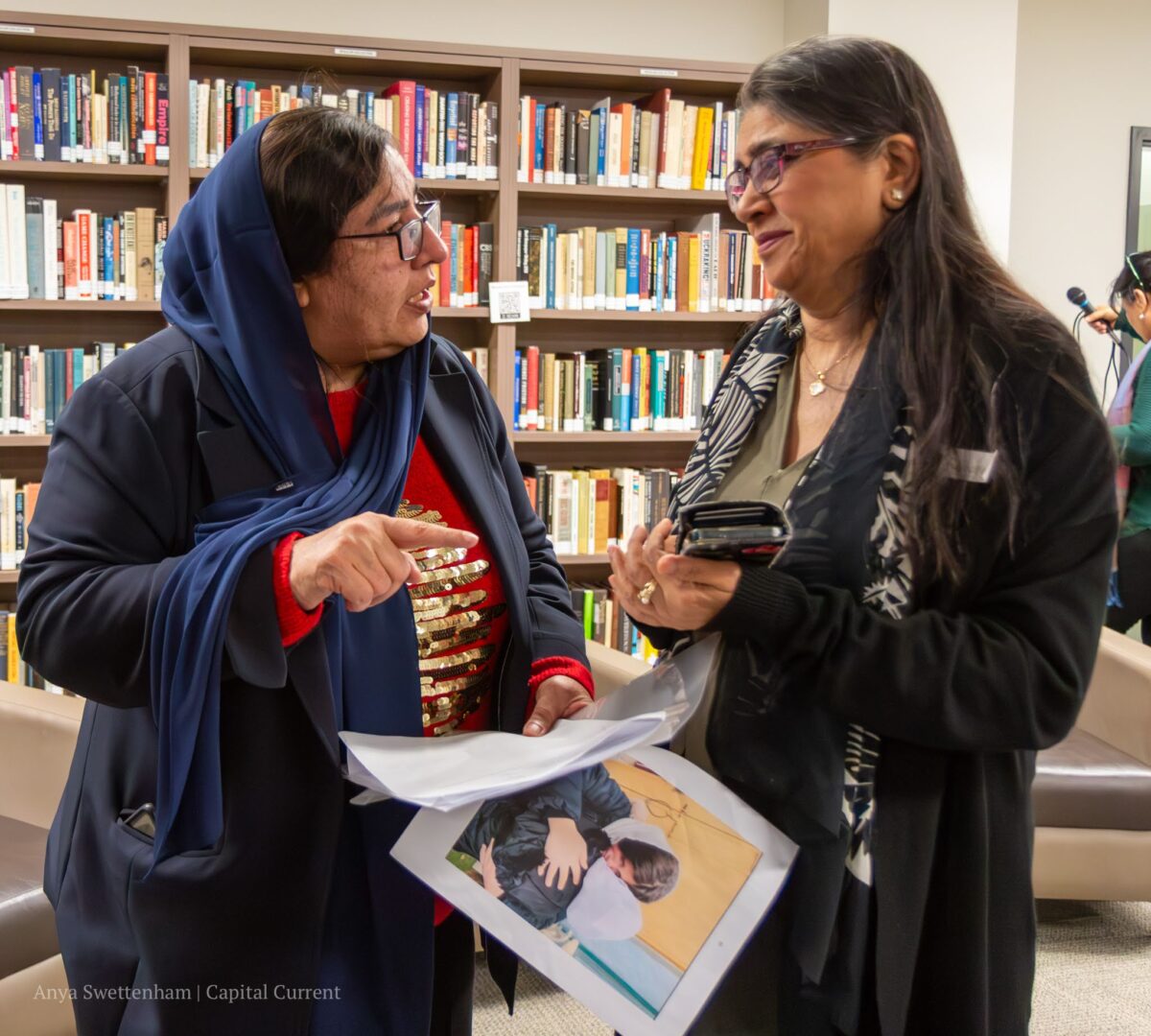

Akbari was one of several prominent Afghan women activists taking part in a panel discussion at Carleton University sharing their experiences of resistance and resilience to mark the 16th day of a global movement to tackle gender-based violence.

“Our resistance shows that we are not people who are always victims, but we also advocate for ourselves. We educated ourselves in a challenging way,” said Naija Haneefi, a founding member of the Ottawa chapter of Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan, which co-organized the recent event with University Women Helping Afghan Women.

Akbari told the gathering that her husband had supported her pursuit of a post-secondary education after the Taliban was ousted in 2001. But with their resurgence of power in 2021, this education is no longer possible for women and girls.

When the Taliban returned, Akbari said she remembers emailing globally to embassies, non-profits and other humanitarian groups that worked with the country’s Ministry of Women’s Affairs, where she worked at the time, to help evacuate women afraid for their lives.

“I did not receive any kind of answer from the government like the embassies,” said Akbari. “The only people that started answering me were the organizations. At that time, I understood the power of nonprofit organizations, humanitarian organizations.”

These organizations, she said, provided emergency funding and created an evacuation program for those in need.

And returning home could prove to be a fatal decision, she added.

“If I go as a woman defender, as a woman activist, I know I will not be back alive from Afghanistan,” said Akbari.

The only difference today, Manfuza Folad, a former judge and director of Justice for All Organization, said is that Afghan women have become educated, have built awareness and have raised their capacity to fight back.

“If we have women who are knowledgable with literature. They never keep quiet. They will stand against them,” said Folad. She then quoted the Persian poet Saadi Shirazi:

“Human beings are members of a whole, In creation of one essence and soul.

If one member is afflicted with pain, Other members uneasy will remain.

If you have no sympathy for human pain, The name of human you cannot retain.“

Folad said she hopes newer generations will remain committed.

“If you come together. If you support Afghan women. If you support us, we will do something. We will bring change,” said Folad. “But it is impossible to do this alone.”

The Taliban has cracked down on women’s rights, including banning women from working with the UN and even closing beauty salons. These bans remove safe spaces and income for women but they also put the lives of children at risk.

Razia Sayad, a lawyer and human rights activist, said during 2023, the Taliban has continued to restrict women’s lives in Afghanistan, including their appearance, freedom of movement, right to work or study, right to assemble in associations and access to entertainment.

“They detained, tortured and publicly punished women who resisted and they continued nullifying laws and legal systems protecting women’s rights,” said Sayad.

She said in one word, Afghan women are being erased from public life and imprisoned in their homes.

Homes where girls are now at risk for child marriages, making them more likely to experience domestic violence, discrimination, abuse and poor mental health, according to a 2021 statement by UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore.

The Taliban Ministry of Virtue and Vice has even decreed that women can’t leave their homes unless necessary and requiring them to cover their faces in public.

Sayad said that solidly documenting cases and crimes that happen against women is the only way to achieve justice, but she did offer three ways for those wanting to combat gender discrimination.

“I would like to call on the international community, particularly to Canadian friends who join us today, to continue pressure to prevent normalizations of what I taught about gender apartheid and help with providing asylum and protection to victims and survivors of Taliban atrocities,” said Sayad. “Help us amplify the voices of Afghan women and children.”

For Azada Azad, a volunteer for Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan and co-president of uOttawa’s Afghan Student Association, this also means sharing the stories of those who are underrepresented in the crisis.

“There’s so much diversity in Afghanistan, but we can’t see them because nobody’s willing to listen to the other voices because one group is being pushed forward,” said Azad. “So it’s important just not to let those voices overshadow your own. You have to be true to yourself. You have to be true to who you are, and you have to always take the chance to speak up to say, ‘Hey, I’m Afghan too. I have the right to do these things as well’.”

Rehana Hashmi, a leader of Sisters Trust Pakistan who was another guest at the event, urged concerned people to write letters that strongly demand support for women from embassies.

“Most of the time, we say it will not really help. I’m telling you, it helps,” said Hashmi.

Still, the most significant changes often come from the people than the government.

Haneefi said it was because of international players deciding who the right people in power were in the first place that led her, like many other women, to fight for the rights her great-grandmother once had.

“As people of the world, which are separate from our government’s policies, we have to raise awareness. We have to make ourselves educated about what’s going on,” said Haneefi.