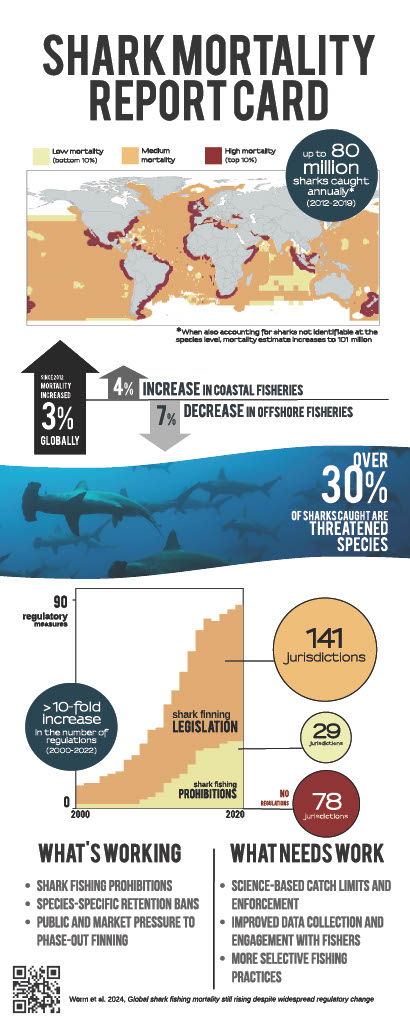

Over the past 20 years, governments around the world have increasingly enacted fishing regulations and finning bans to lower the deadly risk to sharks. But, despite these efforts, shark deaths are rising, a new study shows.

Regulations to protect sharks exist in nearly 70 per cent of maritime jurisdictions. Despite the protections, an estimated 76 to 80 million sharks have died because of finning between 2012 and 2019. The toll rises to about 100 million, the same rate as outlined in a report published in the year 2000, if unidentified shark species are considered, Laurenne Schiller, study co-author and Carleton University post-doctoral fellow in marine conservation science, says. Of those deaths, it is believed that some 25 million were threatened shark species.

“The movement toward protecting sharks by adopting finning legislation is massive. We’ve seen a tenfold increase globally in the number of regulations implemented. And that’s a huge step, not just by one country, but by a lot of countries, which shows people really care about sharks,” Schiller said.

Finning is a practice in which sharks are caught and their fins are removed. Typically, the body of these sharks are thrown back into the sea dead or alive. According to the organization, Shark Stewards, “sharks can not swim without fins and suffer from significant blood loss. They ultimately starve to death or are slowly eaten by other fish. Most drown because [many species of] sharks need to keep moving to force water through their gills for oxygen.”

Despite good intentions, these regulations have not stopped the overexploitation of sharks globally, although some regions have had local success, she added.

Schiller and her colleagues, who published the peer-reviewed study in the journal Science, evaluated the global success of shark protection measures by interviewing experts and linking fishing mortality data to the global regulatory landscape.

Schiller’s team recommends more transparency and accountability is needed for fishing companies, fleets, and management bodies to reverse the decline of shark populations. In particular, they say domestic fisheries management, catch monitoring and enforcement needs the most improvement.

“Even at a national level like Canada, we don’t collect the best data when it comes to bycatch species, and so we don’t necessarily always know how many sharks are being caught,” said Schiller.

The researchers did find that there has been a decline in shark finning. However, Schiller said there has been a rise in whole shark markets, which has also led to more small coastal shark species, including juveniles, being purposefully caught, she added.

“It’s not about saying that every country has to do the same thing because the problems facing sharks are very different in each country. But it’s about saying that every country should be doing something, especially in places where there are lots of species of threatened sharks,” said Schiller.

Nick Dulvy, a professor of marine biodiversity and conservation at Simon Fraser University, who was not involved in the study, points out that the study’s focus on shark finning regulations is misleading because they were not developed to save sharks’ lives.

“Finning regulations were never intended to reduce the catch of sharks. They were intended to bring the bodies home, eliminate the cruelty, eliminate the waste, and allow us to identify the bodies and get better data to manage the shark fisheries,” said Dulvy.

Instead, he said, researchers should look into how other protective regulations on shark fishing may be more successful at reducing shark mortality. Additional assessments must also be done to evaluate whether shark fishing is sustainable or depletes biodiversity, including which species and which countries’ fisheries are most threatened by these shark fishing practices.

“It’s good that people create thought-provoking work because it inspires other people to do the work to answer these questions,” Dulvy said.

Catherine Macdonald, the director of the Shark Research and Conservation Program at the University of Miami, who did not participate in the research, agreed that there needs to be more discussion about shark fisheries, including their economic and social intricacies at a local level.

“In places where sharks are really important to people’s food security and livelihoods, trying to find ways to achieve sustainability feels both more realistic and more ethical to me than depriving people of access to essential resources,” said Macdonald.

However, everyone has a role to play in conserving sharks and the environments that they depend on, Macdonald added.

In North America, Schiller said that cosmetics often use shark oils in face and beauty creams, and many supplements include shark cartilage. While on vacation, many tourists also purchase souvenirs made from sharks.

“It’s really important for people to remember that you don’t know what kind of fishery caught that shark. You don’t even know if you’re buying something that belongs to an endangered species. And so I think it’s really important that people just reconsider some of their purchasing habits,” said Schiller.

As recognized by the study’s authors, Macdonald said understanding the bigger picture of global shark conservation is important, even if it is almost never fully precise.

“Hopefully, this work really pushes countries and government agencies to ensure that they’re collecting the best possible data when it comes to their fisheries because that’s what researchers like us are working with,” said Schiller.