Robert Parungao is at the mic, describing in detail to an audience at a local art café how a serial killer known as the Cannibal Monster of Yunnan dismembered his victims, possibly selling their flesh in a local market as “ostrich meat.” Just as Parungao stops to take a breath, somebody from the nearby kitchen calls up an order: “Three grilled cheese!”

Everyone bursts into laughter.

And that’s just fine. After all, the standing-room-only crowd at the Art House Café in Ottawa — squeezed together among the paintings, board games and illustrated books about knitting — has come to hear true and gruesome stories about murder with heavy dollops of humour to make it more palatable.

“It’s a safe way to engage with the unsafe,” says co-host Arielle Sterling. “It’s close to home, in that you can relate it back to the way you live your life, but far enough away that it’s not emotionally too much.”

Sterling is one of many avid “murderinos” in the audience – fans of My Favorite Murder, a true crime podcast created by American comedians Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark. Not only did the podcast inspire Parungao and Sterling to co-host the free event, it made people want to tell their own stories of the morbid and macabre.

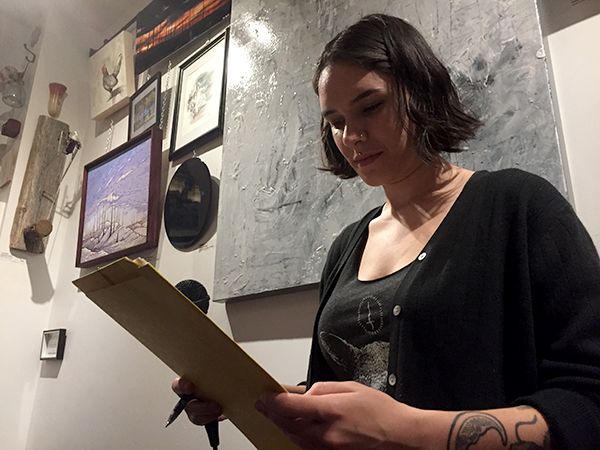

“I was never really into true crime until I listened to this podcast,” says Caroline McLoughlin. But this night, McLoughlin recounts an intricate story that begins with Simpsons’ trivia, travels to the killing fields of Cambodia, and ends with a mysterious assassination in Los Angeles. It’s gripping storytelling.

But for many here, sharing stories about murder is cathartic. “It’s not about glorifying what’s happening at all – it’s just about delving into the horrible, horrible things that happen on this planet, and trying to work out for yourself why it goes on, but with a safe level of removal,” says Sterling.

While research suggests there are many reasons people might be drawn to true crime, our obsession with the genre might function in the same way exposure therapy can. “It may be a very effective way of coping with legitimate fear, but also keeping it in its place — so that we’re not always obsessed by this idea,” says Robert Flynn, psychology professor emeritus at the University of Ottawa.

Sharing stories about murder might also satisfy a desire to learn survival tactics to avoid becoming a victim of violent crime, psychological research suggests.

Anyone can sign up for the open mic, and there are no time limits. The stories are creepy, sometimes shocking, yet full of well-aimed punchlines — a style that follows the formula of Kilgariff and Hardstark.

“I remember listening to the podcast in the grocery store, and I laughed out loud to myself in public, and I like that I can genuinely enjoy myself,” says Sterling. In fact, for the audience and storytellers here, humour is an important part of the equation. “Laughter is a part of being scared. It’s a tension reliever,” explains McLoughlin.

Even though it might seem strange to bring comedy and crime together, chuckling at the outlandish elements of these serious stories is normal. “I don’t think it’s that odd. I think it’s very human,” says Flynn.

Not only are the speakers comical, engaging playfully with the crowd, they are overwhelmingly female. Of the 15 signed up to speak, only two are men. This doesn’t surprise McLoughlin. “Women want something that will tickle our mind over a long period of time. And, it’s a preoccupation for women — especially if you are a minority or have a different sexuality — that you’ve got more of a reason to be paranoid,” she says.

That doesn’t surprise Flynn, either. Even though men are statistically more likely to be victims of violent crime, “that’s small consolation to a woman who is in a dark street and is being followed by a male,” he says.

My Favorite Murder fans have reported escaping being victimized because of what they learned from the podcast, says Sterling. In a Facebook post that has since gone viral, one listener described feeling threatened, but trusting her instincts and heading toward a public area. She eventually fought off a would-be rapist until help could arrive. “I feel like I’ve learned so much from listening to this weekly podcast and I think that it may have helped to prepare me for a situation like this,” Hannah Thees wrote.

“It’s shitty that you have to learn those coping strategies at all, and a podcast seems like a strange way to do it, but there is some real-world value,” Sterling says.

Often their advice is simple common sense, but Kilgariff and Hardstark are opinionated and unapologetic. They demonstrate to listeners that instead of being polite in uncomfortable situations, women should trust the voice inside them that says “fuck politeness,” says McLoughlin.

Stories of near-misses with serial killers or criminals hiding in plain sight are common tonight and on the podcast. They pique our curiosity in a way that might never be satisfied, since some morbid behavior is impossible to explain. “It’s awful but also intriguing, and we like to solve puzzles,” says Flynn.

The podcast, garnering up to 450,000 downloads per week, has popularized a catch phrase: “Stay sexy and don’t get murdered.”

It has also inspired a strong activist strain within the murderino and true crime community, as fans around the world have organized fundraisers for charities. Here in Ottawa, fans have organized a book club: Stay Sexy and Finish a Fucking Book.

This kind of storytelling connects people in a unique way, and with respect for victims, says Parungao. “It brings an element of humanity – not necessarily to the shitty people who do these crimes – but to the people around these crimes. There’s a relatability to ‘this could have been me,’ and all of these other pieces that then connect you to these stories in a way that a newspaper really can’t do,” he says.

Sterling and Parungao say there is an overwhelming appetite for the event in Ottawa, and plan to make it quarterly. “If this event is any indication, there’s still a well to be tapped,” says Parungao.

Follow us on Twitter: @corahansen12 @reportrix @ @jasminemilie12