The city of Ottawa’s much-touted “Housing First” approach to ending homelessness may be creating unique barriers for Indigenous people, who represent a significant proportion of those with no permanent roof over their heads.

The first Point in Time (PiT) headcount of Ottawa’s homeless found 24 per cent of the 1,400 respondents identified as Indigenous. But experts say the actual number of Indigenous people experiencing homelessness is significantly higher.

Indigenous people make up just 2.5 per cent of Ottawa’s total population.

Experts in the housing community say solutions include increasing the amount of affordable housing options, rethinking how people are priorized for permanent housing and ensuring culturally appropriate practices are used to help First Nations, Métis and Inuit find appropriate shelter.

The city’s final report analyzing the findings will be released late this year.

Mark Maracle, executive director of Gignul Non-Profit Housing Corporation, said “poverty is probably the biggest driver” of Indigenous homelessness in Ottawa.

Maracle went on to say Indigenous people also face a “whole range of considerations.”

“A lot of them are suffering intergenerational trauma, poverty, racism, discrimination [and] government policy is driving and has driven Indigenous people from home communities into urban areas.”

Christopher Whalen, who self-identifies as Métis, is a client at the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health.

“The way the people in power took things away from us, it’s very hard to heal from,” he said.

In addition to battling alcohol addiction and chronic homelessness, Whalen says he is a throat-cancer survivor. He is currently living in a bachelor apartment he acquired through his Housing First case manager at Wabano.

Whalen said he was a client at other service providers such as the Shepherds of Good Hope, Ottawa Inner City Health and the Ottawa Mission. He spent many long nights in the Mission’s hospice for close to two years.

“It was too bad that I had to come to almost die to get help.”

The best laid plans

The city’s 2014-2017 progress report on its 10-Year Housing and Homelessness Plan says that many Indigenous peoples do not use city services because of experiences with racism and a lack of culturally appropriate services. Others do not identify as Indigenous, believing that doing so may result in discrimination or poor service.

The city of Ottawa uses what is known as the Housing First model, which moves people experiencing homelessness into housing as soon as possible while providing additional supports as needed.

The Housing First approach

The Homeless Hub, a web-based research library and information centre on Homelessness in Canada, defines Housing First as an approach to end homelessness that centres on quickly moving people into independent and permanent housing, providing additional supports and services as needed.

Though the Housing First model is used by three Indigenous housing service providers in the city – Wabano, Minwaashin Lodge and Tungasuvvingat Inuit – there are concerns about the model’s viability for Indigenous people in terms of how clients’ needs are assessed and addressed with culturally appropriate services, and a lack of actual housing for clients.

The Housing First model typically ranks individuals based on need and duration of homelessness through a questionnaire known as a service prioritization decision assistance tool (SPDAT).

The SPDAT examines different aspects of a client’s life and produces a ranking that determines the level of need for housing and support services.

Assessing and addressing

Tina Slauenwhite, director of Wabano’s Housing First program, said Indigenous providers found clients “were being re-traumatized” by the SPDAT evaluation. As a result the Indigenous service providers stopped using it to assess their clients.

Slauenwhite said they started using criteria created to function more as a “conversation” with clients.

After an assessment, the city’s plan aims to match homeless clients with appropriate affordable housing options, including rent supplements and housing allowances. But there is a problem.

“If you want to be able to end homelessness, which everybody is wanting to do, there needs to be housing. Affordable, safe housing for people to move into, which we don’t have here in Ottawa,” said Slauenwhite.

Even if the housing can be found though increasing the amount of available housing stock or increasing housing allowances, culturally appropriate services are essential to provide Indigenous clients with permanent solutions.

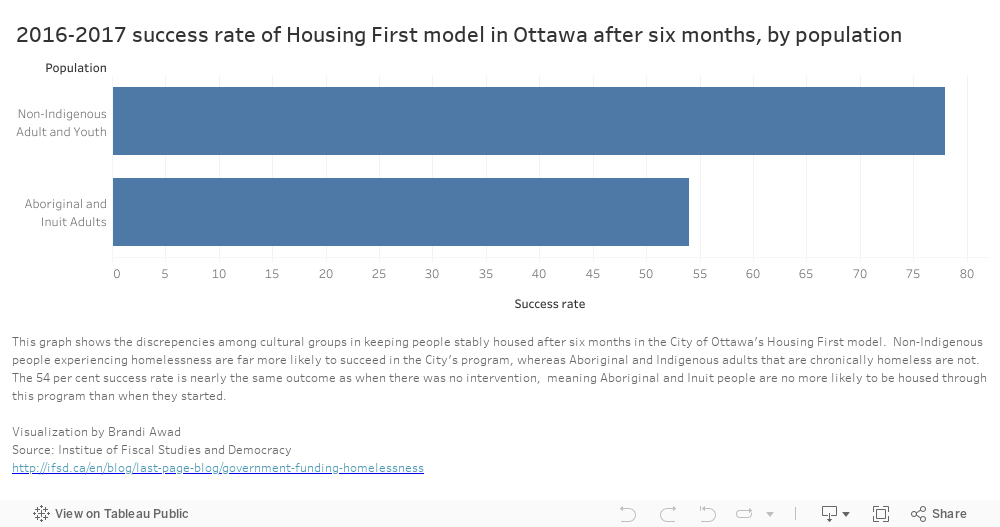

Randall Bartlett, chief economist at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, said the Housing First model has “basically failed this population.”

Although Bartlett noted the success of the Housing First model for the general population in Ottawa in a 2017 analysis on government funding for homelessness programs, the conclusions indicated the approach is not working for Indigenous people.

“The system is not well-designed to ensure that Indigenous people get access to the services that are being funded specifically for Indigenous people.”

Moving forward

Mark Taylor, who represented Bay Ward and was special liaison on homelessness in the last council, acknowledged shortcomings in providing culturally appropriate services across the city.

“We need to explore other models and I think [people in] our Indigenous community are probably the ones in the best position to help guide us through that.”

Taylor suggested abandoning the current method where the city consults with community providers, crafts a plan and puts it in motion. Instead, city staff would work with housing agencies and providers to determine where the money should be invested.

“All I’m advocating for is to bring the people who are actually delivering the services, including the Indigenous services, around that table.”

He recommended this group mandate larger service providers who bid on requests for proposals for housing units to include an Indigenous agency in the build to ensure an adequate number of culturally appropriate Indigenous housing units are created.

Christopher Whalen describes his experience with chronic homelessness. [Video © Dana Hatherly]

For Whalen, the services offered at Wabano have made all the difference.

“Wood carving, beading, teachings from the elders, everything.”

Reconnecting with Indigenous identity “gave me a light, like something inside of me.”

“Like a lot of Indigenous people I know I’ve studied a lot of medicines and stuff like that, and the hope in there gave me the hope to keep going,” he said.

Related links

- Survey details Ottawa’s homelesss population

- Symbiosis housing project may offer solutions for seniors, students in Ottawa

- Heron Gate evictions point to growing affordable housing crisis in Ottawa

Your reporting has captured much Insight. Thank you.