This summer’s heat has broken records in Canada and it’s likely going to get warmer.

Lytton, B.C., gained international infamy after it experienced the hottest temperature ever recorded in Canada at 49.6 degrees Celsius in June. According to a 2019 report from the Prairie Climate Centre, heat waves will become hotter, longer and more frequent.

Homeless people are those most exposed to the elements, says Dr. Sean Kidd, a clinical psychologist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, who has studied the impact of climate change on homelessness.

Homeless people are affected by climate change to a far greater extent, he says.

“When there’s already existing systemic discrimination, this kind of a global risk will play out with disproportionate impacts on people who are already stigmatized.”

Dr. Sean Kidd, clinical psychologist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto

Statistics Canada estimates Canada has between 25,000 to 35,000 people experiencing homelessness on any given night and some 235,000 go homeless each year; a number that is increasing.

“People in this situation are often living in some of the hottest places in our urban environments, in the downtown core where there is very little greenspace and shade and accessible water, all of the stuff you need to survive and maintain your health during temperature and weather extremes,” Kidd said.

Heat waves and their effects are more devastating in cities, because of the urban heat island effect. It is the result of densely packed buildings and paved surfaces such as roads and sidewalks which trap heat more effectively than natural ecosystems, according to the Climate Atlas of Canada. Pavement can be up to 50 degrees hotter than the surrounding air, making cities 12 degrees hotter than the countryside.

Many cities do not provide enough public water fountains or public washrooms where those experiencing homelessness can get water and stay hydrated, Kidd said.

Many cities shut off water fountains over the past year because of a fear of COVID-19 transmission. This summer, Hamilton, for example, initially announced it would only run a quarter of its public water fountains, but then opened all of them after community advocates raised concerns.

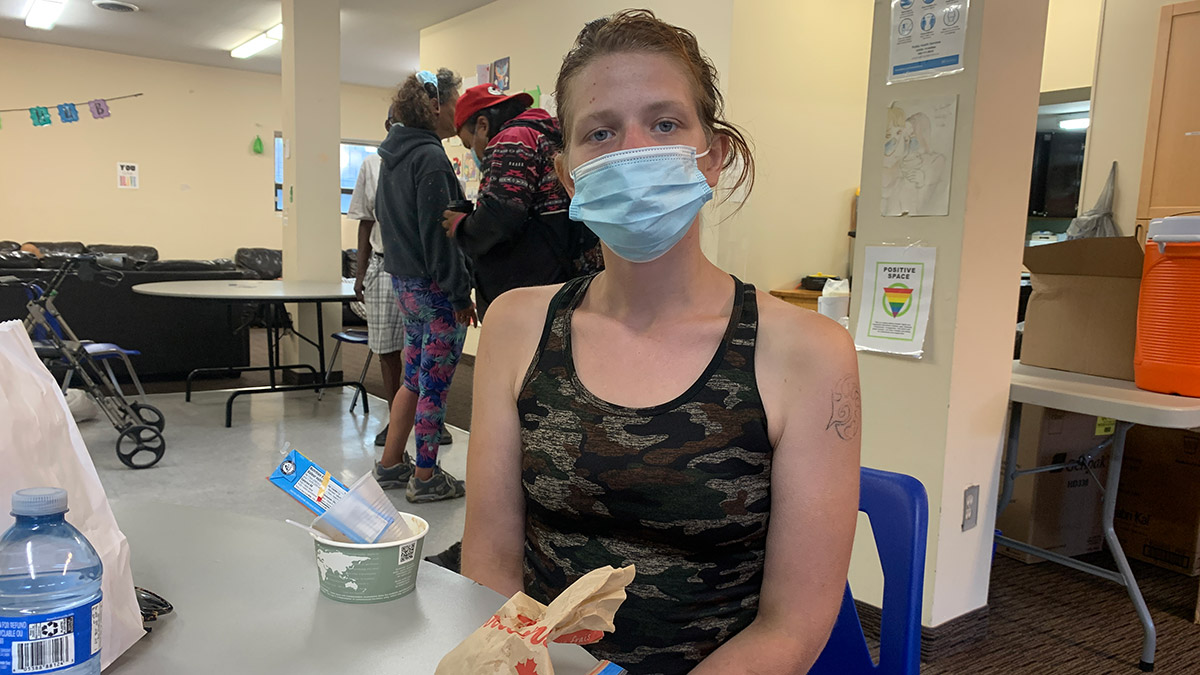

Homeless people can develop heat stroke very easily, especially if they’re dehydrated, said Dana, a homeless advocate in Hamilton, and volunteer at the Hub Hamilton. She has experienced heat stroke this summer, while setting up her tent.

“The heat — you can’t get away from it. You pass out because of exhaustion and get burnt,” she explained. “The sun tends to attack you, if you’re on drugs and dehydrated.”

People can start hearing and seeing things, Dana explains. "It's kind of like you get schizophrenia from the sun — you're up for days without realizing you're awake for days."

It is essential to stay hydrated to survive the heat, Dana says, which can be very difficult when water fountains are turned off and one is not able to use public washrooms. She says some people have broken into construction sites to use the port-a-potties.

In 2010, Steven Samra wrote an article on the effects of extreme heat on homeless people. What has changed since, he says, is that it's hotter in more places and there are more homeless people.

Samra is a senior associate with Nashville-based C4 Innovations, an organization which supports the recovery of people with addiction and behavioral health problems.

"If you look across the homeless population, often you will find old folk, young people and people with serious health conditions," says Samra, noting that the same population of people can be affected by heat in a life-threatening way.

"The sun tends to attack you, if you're on drugs and dehydrated.”

Dana, homeless advocate in Hamilton

There are three heat-related illnesses — heat cramps, heat exhaustion and heat stroke, Samra explains. Heat cramps are mild, but can progress to heat exhaustion, where people feel confused and thirsty, and they may get a headache, he says. Heat exhaustion, if untreated, progresses to heat stroke.

"That's a medical emergency and that person has lost the ability to perspire, basically, and they are boiling themselves to death,” says Samra. "If a person's in heat stroke, that's an ambulance medical emergency level."

If people experience heat exhaustion, they shouldn't be forced to go back out into the heat for at least 24 hours, but if cooling shelters close at the end of the day, then there is little choice. "It is extraordinarily dangerous even when a city has it together, and the truth is most cities don't have any of this together," Samra says.

Cities should think outside of the box to find ways to protect homeless people from heat waves, says Samra. Libraries could become designated cooling centres, and already come equipped with plenty of reading material, free Internet and public restrooms, he says.

Cities should also have set plans for heat emergencies, Samra notes. The moment it hits 32C, for example, cities should automatically trigger a heat emergency response, he says. Cooling shelters should be open, and a fleet of heat patrol vehicles should make regular rounds through the city, providing cold water bottles and transportation to cooling centres for those who want it. Street outreach workers should also be trained to recognize heat-related illness.

It is important to ensure access to washrooms and showers, Dana says. She suggests cities or organizations create shade in downtown cores with big tents, as homeless people cannot often find shade without being considered "loiterers.”

More hydration stations and more public pool access can also help to keep homeless people active and cool, she explains.

Many cities are looking at climate resilient strategies, which involves assessing and mapping the hotter and cooler parts of the city, says Kidd. Creating more shady spaces is paramount, but Kidd warns that without including poor people in climate remediation, the effect of this may be paradoxical. "Greening a downtown environment drives up housing costs and actually makes it less affordable."

Homeless or inadequately housed people have to be involved in all levels of planning, Kidd says, whether it is green infrastructure, housing design or outreach programs.

Climate change is a major stressor and real risk for all of us, says Kidd. "When there's already existing systemic discrimination, this kind of a global risk will play out with disproportionate impacts on people who are already stigmatized," he says.

It is unacceptable that Canada has people experiencing chronic homelessness, Kidd says, and so if people are not homeless, they are not exposed to the extreme weather. "It's something that I think we need to call out so that we're not considering it a baseline acceptable that we have people exposed in these ways."